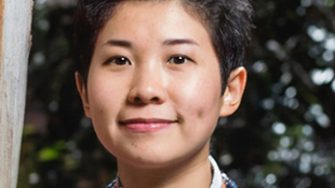

SPOTLIGHT: A/Professor Xiaoqi Feng: Impact driven - changing the environment to save lives

With a focus on promoting more liveable, healthier and equitable communities, leading epidemiologist Xiaoqi Feng is Associate Professor in Urban Health and Environment at UNSW School of Population Health,...