Outlaw culture: Aboriginal women and the power of resistance

From bushrangers to community matriarchs, Aboriginal women have found many ways to empower themselves and their people through acts of resistance – within and outside of the law.

From bushrangers to community matriarchs, Aboriginal women have found many ways to empower themselves and their people through acts of resistance – within and outside of the law.

Associate Professor Nicole Watson wants to tell you a story. This is a story that has been pushed to the margins by false and pervasive Australian foundational myths.

“Myths that conceal a troubling truth,” Watson says.

But this is a story that refuses to be ignored. They are stories found in the voices and acts of Aboriginal women – who are often rendered voiceless and invisible through history and in legal judgements.

At the margins, a rich history of Black women and their resistance to oppression and subjugation emerges. A history that has always existed and persists today.

It is here that the tales of bushrangers, warriors, escapees, matriarchs, plaintiffs and protesters come to life. Stories of outlaws and their unrelenting power.

Watson, who is the Director of Nura Gili Academic Programs at UNSW, has always understood the power and importance of storytelling. Growing up in an Aboriginal – Munanjali and Birri Gubba – family of storytellers, “it's in our blood”, she says.

“As the Indigenous writer, Thomas King once wrote: The truth about stories is that’s all we are.

“And while King’s words are universal, for Indigenous peoples storytelling takes particular significance. It's how we receive our culture, Law, family histories, and the tools to lead a good life.”

Associate Professor Nicole Watson is a Murri lawyer, writer, and the Director of Nura Gili Academic Programs at UNSW.

These stories, Watson says, also contest the pervasive myths that render Aboriginal peoples invisible; or paint “us as mere caricatures and silhouettes of human beings”.

When Watson was introduced to a new form of storytelling during her time at law school in the late '90s – that of legal judgements – she realised that the community, family and kin of her childhood were absent in them.

“As we would study significant cases, I realised that even the stories of giants – such as John Koowarta and Eddie Mabo – are treated as irrelevant in judgements. They are dehumanised. This invisibly is pervasive, I would come to find, and no more so than for Aboriginal women.”

It is through engagement with critical race theory and outsider storytelling, that this veil can be lifted, Watson says.

“By focusing on the stories of the marginalised, we see the power and humanity of Aboriginal women that has often been overlooked by scholars, and more broadly by Australian society.

“Through engagement with these narratives of outsiders, we can give a voice to those who have been dehumanised by laws that are ostensibly neutral and challenge the prevailing narrative that racism has become a mere aberration.”

Aboriginal women have been at the vanguard of an outlaw culture, Watson says, which consists of empowering practices that have been created in response to the ongoing denial of the law’s protection.

This outlaw culture draws “its power from deception” – a concept that Watson derives from a paper by Assistant Professor of Law, Monica J Evans, on African American women and outlaw culture in the United States.

Throughout history, Aboriginal communities have also been “denied the protection of the law and stigmatised as dangerous, deficient and deviant”, Watson says.

A/Prof. Watson's new book 'Aboriginal Women, Law and Critical Race Theory' explores how outlaw culture finds expression in a diversity of relationships with the law. Photo: Shutterstock

Those who have shaped outlaw culture, therefore “use their marginality as a veil to mask traditions and tactics of resistance”.

“This deception is manifest in a broad spectrum of behaviours that range from aggressive – and perhaps illegal acts – to scrupulous compliance with the law.”

These acts of resistance give Aboriginal women autonomy over their oppressors and contest racist tropes that have come to define Aboriginal women in the national imagination.

Throughout Australian history, Aboriginal women were entitled to the protection of the law.

“But in reality, that counted for little. Today this truth is barely acknowledged,” Watson says.

Racist tropes that maligned and diminished Aboriginal women were used to cover up the brutality of invasion and the frontier.

Read more: A decade at the UN – Indigenous rights expert says 'our fight continues'

Watson says this can be seen in examples such as the trope of ‘bride capture’, highlighted in Liz Connor’s book Skin Deep: Settler Impressions of Aboriginal Women.

“From the moment of their courtship, Aboriginal wives were portrayed as the victims of their brutish Aboriginal husbands who forced them into lives of drudgery.

“Tropes such as that of ‘bride capture’ enabled settlers to view colonisation as an exercise in chivalry. Rather than being complicit in an invasion, they were bringing the benefits of civilisation to an inferior race.”

The Leap Hotel sits at the foot of the mountain where Kowaha leapt to her death. An unflattering statue of Kowaha stands out front. Photo: Facebook

The Aboriginal women who met horrific ends at the hands of settlers on the frontier remain largely nameless and their stories are erased, in place of these narratives.

Growing up in Queensland, Watson was very aware of the lack of monuments that acknowledge the brutal history of colonisation and dispossession.

One area, however, is still defined by a tragedy of the frontier.

The Leap in the Mackay region is a town that took its name from the death of an Aboriginal woman who was known as Kowaha in the 1860s.

Following the discovery of speared cattle, the native police – a government-funded paramilitary force – set out to conduct a “dispersal”.

The term dispersal was a euphemism in nineteenth-century Queensland for the indiscriminate killing of Indigenous people.

“...the native police have been sent to disperse them. What disperse means is well enough known. The word has been adopted into bush slang as a convenient euphemism for wholesale massacre.”

- The Queenslander editorial, 1 May 1880 (quoted in 'The Way We Civilise' by Rosalind Kidd).

Together with her infant daughter, Kowaha sought sanctuary on the summit of what is now known as Mount Mandarana.

“Perhaps realising that it was only a matter of time before the native police captured them, Kowaha leapt taking her child with her,” Watson says. The child miraculously survived and was raised by settlers.

Today, a pub called the Leap Hotel sits at the foot of that mountain. Out the front of the pub stands an unflattering statue of Kowaha.

Read more: Strip-searching shows discrimination against Aboriginal women

“It is difficult to imagine the terror instilled in women such as Kowaha. Women who watch their families, homes, indeed everything that had defined their worlds were devastated by invasion and then ongoing colonisation.

“But among the stories of tragedy and terror, are those of outlaw women.”

One manifestation of outlaw culture is those Aboriginal women who broke the law to reclaim their autonomy.

The names of these women who took up arms are unknown to most Australians, Watson says.

A rare expectation is Palawa warrior and resistance fighter Walyer, who was born in what was then known as Van Diemen’s land in the early nineteenth century.

“As a young woman, Walyer was sold to sealers in exchange for dogs and flour. After escaping from her captors, Walyer taught members of her clan how to use firearms and led their resistance against the settlers.

“Walyer became notorious for hurling insults at her enemies during attacks and reportedly said that she liked the white men as she did a black snake.”

Walyer’s “brief but momentous life” ended after she contracted influenza in 1831.

Worimi woman, Mary Ann Bugg formed a relationship with Frederick Wordsworth Ward – known as Captain Thunderbolt, the “gentleman bushranger”. Photo: McCrossin's Mill Museum, Uralla.

Other outlaw women secured a degree of autonomy by establishing relationships with male bushrangers.

Among them was Mary Cockerill and Mary Ann Bugg.

Cockerill – also born in Van Diemen’s land in the eighteenth century – “would go on to participate in raids on hapless settlers” after eloping with bushranger Michael Howe.

Decades later, Worimi woman, Mary Ann Bugg formed a relationship with Frederick Wordsworth Ward – known as Captain Thunderbolt, the “gentleman bushranger”.

Read more: Landmark book answers all your questions about the Uluru Statement

Ward is infamous for escaping from Cockatoo Island. History has largely ignored how vital Bugg was to his success however, Watson says.

Over several years, Bugg would become Ward’s chief lieutenant and played a key role in his raids and strategies to evade police.

“Women such as Mary Ann not only shared their knowledge of Country with their partners but they incorporated the men into their family relationships.

“Aboriginal kin armed the likes of Ward with valuable information about police movements thus enabling them to evade capture.”

We will never know the precise motivations of women such as Mary Cockerill and Mary Ann Bugg, Watson says.

“But is possible that by becoming bushrangers both women achieved a degree of equality and independence.”

Later, outlaw women resisted their oppression by fleeing from authorities and drawing upon their shrewdness and experiential knowledge to survive.

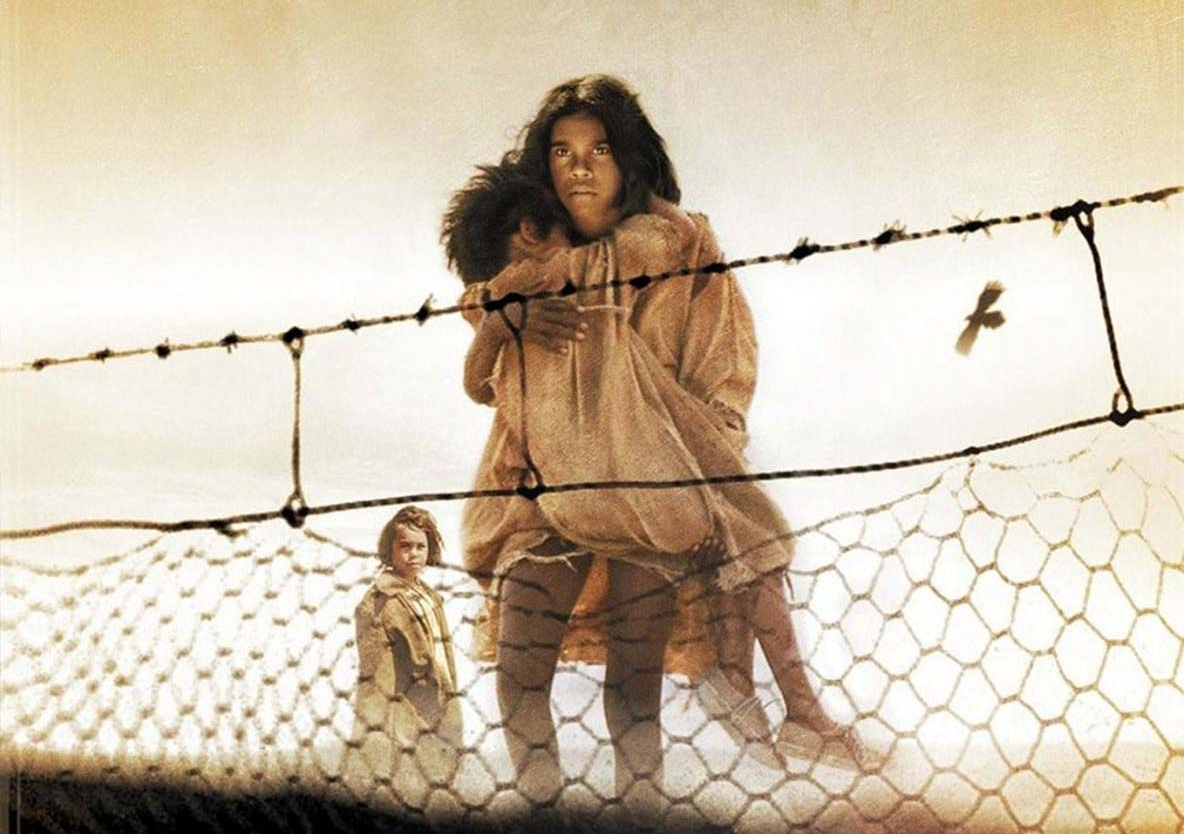

“This expression of outlaw culture was epitomised by Molly and Daisy Craig and their cousin, Grace Fields – whose story would be memorialised by Doris Pilkington's book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence and then an award-winning film by Phillip Noyce,” Watson says.

Doris Pilkington's novel Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence memorialised the journey of Molly, Daisy, and Grace. Photo: UQP.

“Three children were removed from their families in Jigalong, in the northwest of Western Australia in 1931. Their inconsolable relatives were informed by a police officer that the girls would be sent hundreds of miles away to the Moore River Native Settlement to receive an education.”

Faced with the reality of the settlement, more akin to a penitentiary, the children would escape – using their knowledge to follow a rabbit-proof fence some 1600 kilometres back to their family.

Molly, Daisy and Grace survived by hunting rabbits and other small animals, as well as getting food from remote farmhouses.

“Key to their success was giving adults false information to evade capture and thwart authorities. Even at a young age, they knew how to use their marginality to their advantage.”

Other Aboriginal women, Watson says, went on strike to resist oppression.

The participation of Aboriginal women domestic workers in the well-known Pilbara Strike has been largely overlooked, she says, but Aboriginal women were key to the eventual success of the strike.

“By making their labour visible by withdrawing it – which for so long was forced, invisible and denigrated – Aboriginal women showed how it was they who maintained much of station life.”

Overt defiance is one expression of outlaw culture.

Another is to “create safety by remaining within the confines of the law, and using one’s marginality as a space to create practices and tactics of resistance”.

Aboriginal women, for generations, have drawn upon their resourcefulness and ingenuity to protect the most vulnerable members of their communities.

Many Aboriginal women, Watson says, provided social welfare before Aboriginal services were established in the ‘70s.

"Our home became a merry go round of Uncles, Aunts, cousins and restless souls who found an anchor in our family.”

“The life stories of Indigenous women are replete with characters who assumed responsibility for children within their extended families and communities.”

“Matriarchs played such an important role in my childhood too. Namely, my paternal grandmother: Nanna.

“It was under Nanna’s influence that our home became a merry go round of Uncles, Aunts, cousins and restless souls who found an anchor in our family.”

Students at Murawina – Aboriginal preschool and childcare – on Eveleigh Street, Redfern in 1980. Photo: National Archives of Australia (Series A6180, Item 22/4/80/16)

“Nanna was demure”, Watson says, “but beneath that exterior was an outlaw who defied so many of the negative representations and low expectations that mainstream society imposed upon Aboriginal women.”

Read more: Redfern rising – the story of Aboriginal activism in the 1970s

The women of Watson’s grandmother’s generation were also instrumental in the creation of Aboriginal services in the ‘70s – such as Murawina, the Aboriginal preschool and childcare centre in Redfern.

Other contemporary forms of outlaw culture have emerged, through attempts to harness the law, despite Aboriginal women’s invisibility in judgements.

Outlaw culture also involves tactics to harness the law. Photo: Unsplash.

Through this manifestation of outlaw culture, Aboriginal women attempt to protect their rights and their connections to Country using the mechanisms of law. They also do so through protest.

“Indigenous women have never been submissive victims of colonisation,” Watson says.

“Despite the horrors of invasion, and later the denial of personal freedoms under the policy of protection, Indigenous women created the means to reclaim their autonomy and that continues today.”

Why should all Australians engage with the stories of Indigenous outlaw women? Why do their stories matter?

They matter, Watson says, “because the lives of Aboriginal women matter”.

“Outlaw women also appreciated their own power. They refused to accept the lowly roles that society had carved out for them.

“During a time when our values have become warped; when our political leaders appear to care little for the various crises that will be the inheritance of future generations, we would do well to engage with the stories of these remarkable women.

“After all, Australians have much to learn from the brilliance of Black women.”

Associate Professor Nicole Watson’s book, Aboriginal Women, Law and Critical Race Theory: Storytelling from the Margins is out now.

Watch A/Prof. Watson’s Wingarra Djuraliyin Public Lecture on Indigenous Peoples and Law on Aboriginal Women, the Law, and Outlaw Culture.