THE CONVERSATION: Masks, RATs and clean air – how people with disability can protect themselves from COVID

People with disability bear a disproportionate burden of COVID infections, serious disease and

People with disability bear a disproportionate burden of COVID infections, serious disease and

People with disability bear a disproportionate burden of COVID infections, serious disease and death. Every time a support worker enters their home, people with disability risk COVID exposure.

But while Australian states have evidence-based measures to reduce the spread of COVID in schools and hospitals – such as improving ventilation, mandating masks, and using rapid antigen tests to detect cases – few strategies exist to reduce transmission to people with disability in their homes.

Last Thursday, Australia’s disability royal commission released a “statement of ongoing concern” about how Omicron is impacting the health, safety and well-being of people with disability.

So what do governments need to do to protect people with disability from COVID? And what can people with disability do to mitigate their risk in the meantime?

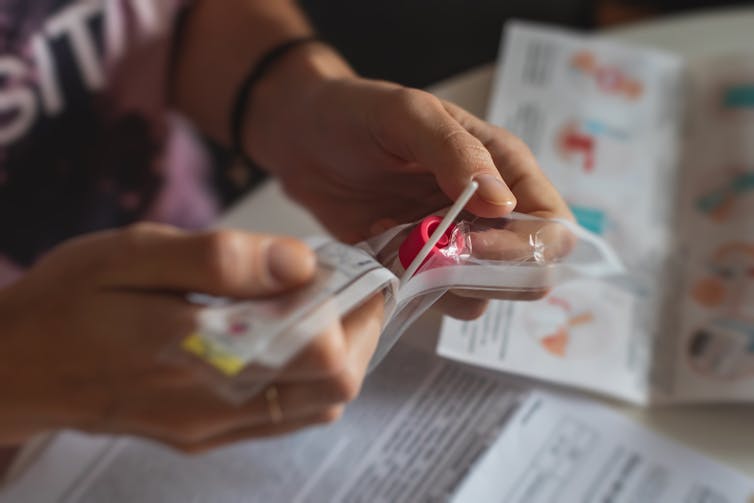

When community prevalence of COVID is high, rapid antigen tests (RATs) are an important tool to identify cases of COVID and prevent transmission.

But RATs are not freely available to all Australians with disability. And there is no clear advice about how RATs should be used by people with disability or support workers who enter their home.

While National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) participants can claim the cost of RATs in their NDIS plans, they’re not currently recommended for surveillance of workers, except those working in group homes.

But not all Australians with disability are on the NDIS. Nor are all people with disability on health care cards and entitled to ten free RATs every three months.

RATs should be free for people with disability and their support workers. Shutterstock

Given the risks of COVID and the high levels in the community, free RATs should be provided to all people with disability and support workers who come into their homes.

This should come with clear guidance on how frequently to test workers and other people who come into contact with a person with a disability.

In the absence of clear guidelines, support workers should test at least twice a week. But daily testing might be required where a worker is in contact with many people and when someone with a disability is at high risk of serious disease or death if they catch COVID.

However some caution is needed. When there are high levels of community transmission, one negative RAT in someone with symptoms may well be a false negative. So someone with symptoms should isolate irrespective of the RAT result.

Cloth and surgical masks are not enough to prevent the spread of Omicron.

Respirators, also called N95, P2, FFP2 and KF94 masks, offer substantially better protection. Respirators cut transmission 2.5 times as much as surgical masks, even when they haven’t been professionally fit-tested. And there are good online videos and infographics to help people ensure their respirators have a good fit.

Respirators should be well-fitted. Shutterstock

Respirators can also be re-used, rotating daily over five days, as independent scientific advisory group OzSAGE recommends.

The United States government is providing free respirators to the public, yet Australian governments only recommend respirators in the disability sector when someone with disability is COVID-positive or a worker is a close contact.

Given the obvious benefits, and relatively few downsides of respirators, it’s critical they are mandated for disability workers when supporting people with disability indoors.

In the absence of guidelines, people with disability should get workers to wear well-fitted respirators when they are supporting them indoors.

Good natural or mechanical ventilation can reduce COVID transmission.

This can involve simple measures such as opening doors and windows – preferably at the opposite ends of an indoor space to ensure a cross-breeze – and using ceiling fans or pedestal fans placed near a window.

Sometimes it’s not possible to open doors or windows because it’s too hot or cold, especially given some people with disability, such as those with spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis have greater difficulties regulating their temperature.

Spaces like toilets, bathrooms, lifts, and stairwells are also hard to ventilate.

Opening a window can improve ventilation, but that’s not always possible. Shutterstock

You can check the quality of the air inside using CO2 monitors. The concentration of CO2 is higher in areas that are poorly ventilated, while outside it’s around 400 ppm. If the level is below 800 ppm, the risk of infection is relatively low.

In situations where CO2 levels are high, a portable HEPA air purifier could be used. The HEPA filter helps remove very small particles from the air, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID. They range in price from A$200 to A$2,000.

CO2 monitors vary in design and cost, with prices starting from around A$50.

CO2 monitors and air purifiers should be available to people with disability requiring support in their own homes for free, potentially through NDIS plans.

In group settings, such as day programs and disability residential settings, services should be required to audit CO2 levels and purchase air purifiers if needed.

In the absence of clear guidance on ventilation, people with disability should make sure they have as good an airflow as possible and check their air conditioning and heating are working properly.

If they have the resources, they could purchase a CO2 monitor (or borrow one from someone) to check ventilation and where CO2 levels are high, consider an air purifier.

Nearly two years into the pandemic, it feels like Australians with disability are being forgotten.

Mandatory respirators, RATs for surveillance and cleaner air are relatively inexpensive strategies critical to protecting people with disability in their home. Governments should provide free of cost for all people with disability who need them, not only NDIS participants.

Governments must be proactive and have guidelines and resources in place as we face Omicron and in future, as new variants emerge.![]()

Anne Kavanagh, Professor of Disability and Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne and Helen Dickinson, Professor, Public Service Research, UNSW Canberra.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.