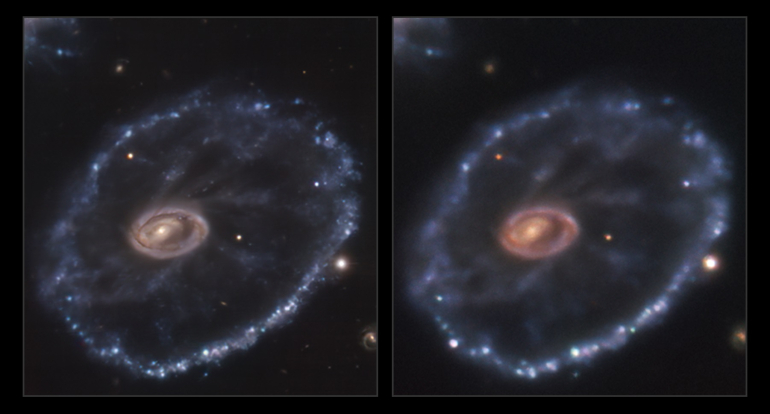

UNSW Canberra astronomer Dr Ivo Seitenzahl has captured a series of images that depict a stellar explosion in the Cartwheel galaxy, about 500 million light years away from Earth.

Released this month by the European Southern Observatory, the composite image was created by combining nine individual photos that were captured by Dr Seitenzahl on 4-5 December, 2021.

Located in the constellation Sculptor, the Cartwheel galaxy was named for its unusual appearance. Once a typical spiral galaxy, its signature cartwheel appearance was formed when it collided with a smaller companion galaxy.

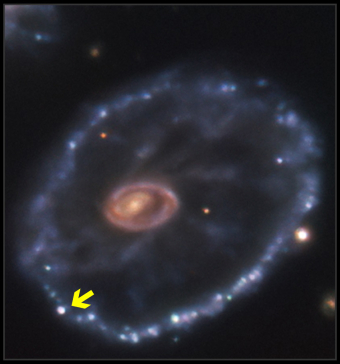

The newly discovered supernova, named SN2021afdx, can be seen on the bottom left of the galaxy.

“Observations of the supernova allow us to classify it and to determine what kind of supernova it is,” Dr Seitenzahl said.

“We now know that SN2021afdx was a "Type II" supernova, characterised by hydrogen absorption lines in their spectra. Type II supernovae are the result of massive stars that have reached the end of their lives.

“They have converted the nuclear fuel in their core to iron. At some point, the iron core is so massive that it collapses under its own weight and forms a neutron star or even a black hole. The associated explosion of the outer layers of the star produces radioactive isotopes, such as 56Ni, which decays and heats the explosion ejecta to high temperatures for it to shine brightly as a supernova explosion.”

The discovery of the supernova was the product of an international collaboration. SN2021afdx was first spotted in November 2021 by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) Survey.

It was then sighted by the advanced Public ESO Spectroscopic Survey for Transient Objects (ePESSTO+), which is designed to study objects that are only in the night sky for very short periods of time.

Dr Seitenzahl captured the images via ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile.

“I had volunteered to take over this particular observing run as a service to the ePESSTO+ collaboration,” Dr Seitenzahl said.

“I ultimately decided that we should observe the target, and when and how to do it. I had to prepare the observing run by selecting the targets and populating the observing queue with what are essentially computer files that contain all the instructions of how to operate the instrument – for example, where to point the telescope, how long to expose, how many exposures to take, what filters and gratings to use and what calibrations to take.

“Then I stayed up all night, well, all ‘Chilean night’, which luckily is daytime over here in Australia, and decided which observations to do and when, according to the sky conditions at the time.”

Dr Seitenzahl said ground-based observing requires the astronomer to remain flexible and to adapt to the atmospheric conditions, which change throughout the night.

“The sharpness of an image and image quality depend on how stable the atmosphere is at the time,” he said.

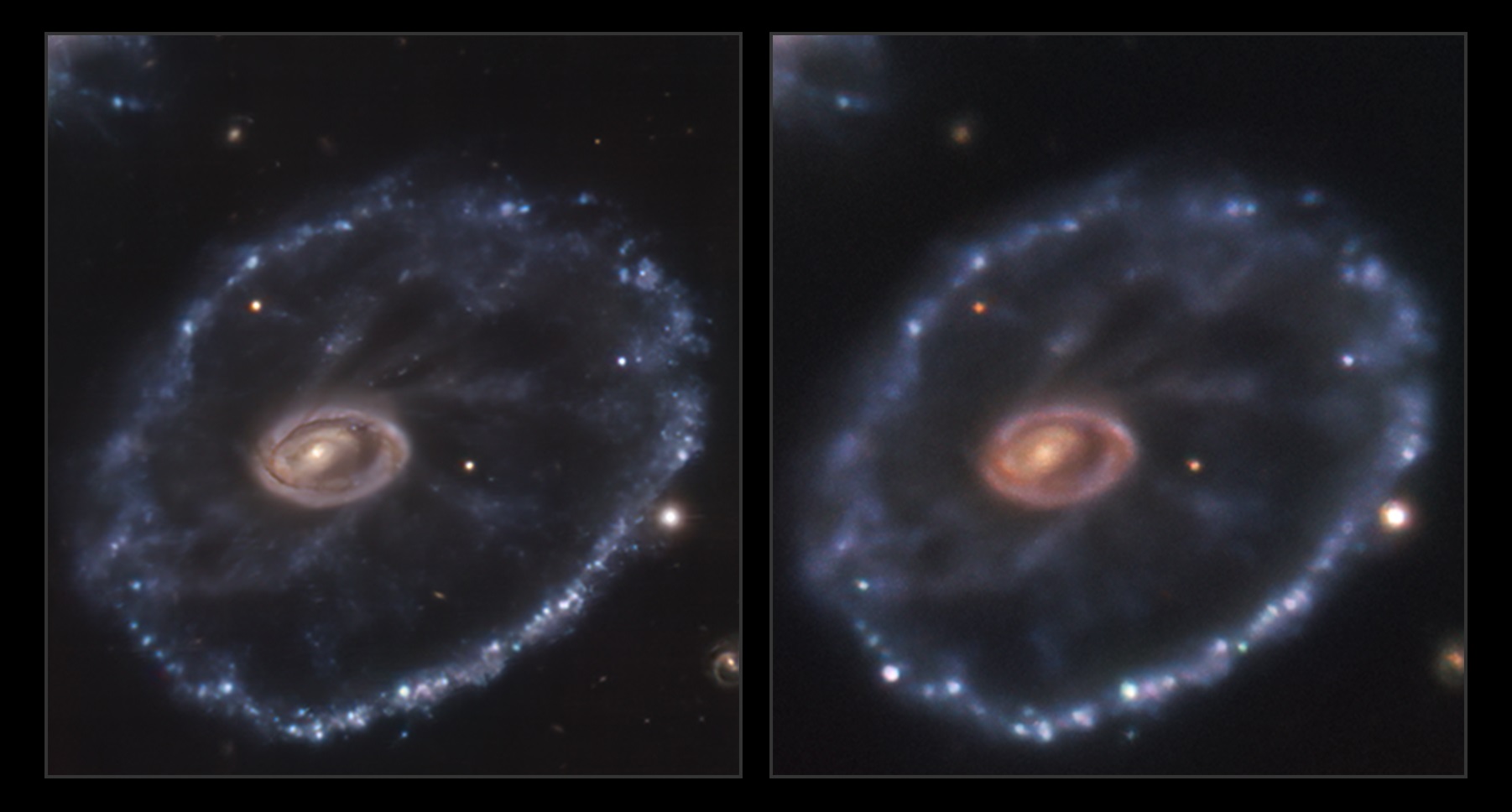

Dr Seitenzahl attempted the imaging observations of the supernova on two consecutive nights, however conditions were not ideal on the first attempt.

“By the time we had acquired the target and we started taking images, the atmospheric conditions had worsened, and the resultant images were more blurry than what we had hoped for,” he said.

“I therefore tried again the following night and that time we got lucky, and we could get the data for the beautiful image that you see.”