Navigating the future: the promise of autonomous boats

A UNSW maritime law expert says autonomous vessels are on the rise – and with them, potential legal challenges.

A UNSW maritime law expert says autonomous vessels are on the rise – and with them, potential legal challenges.

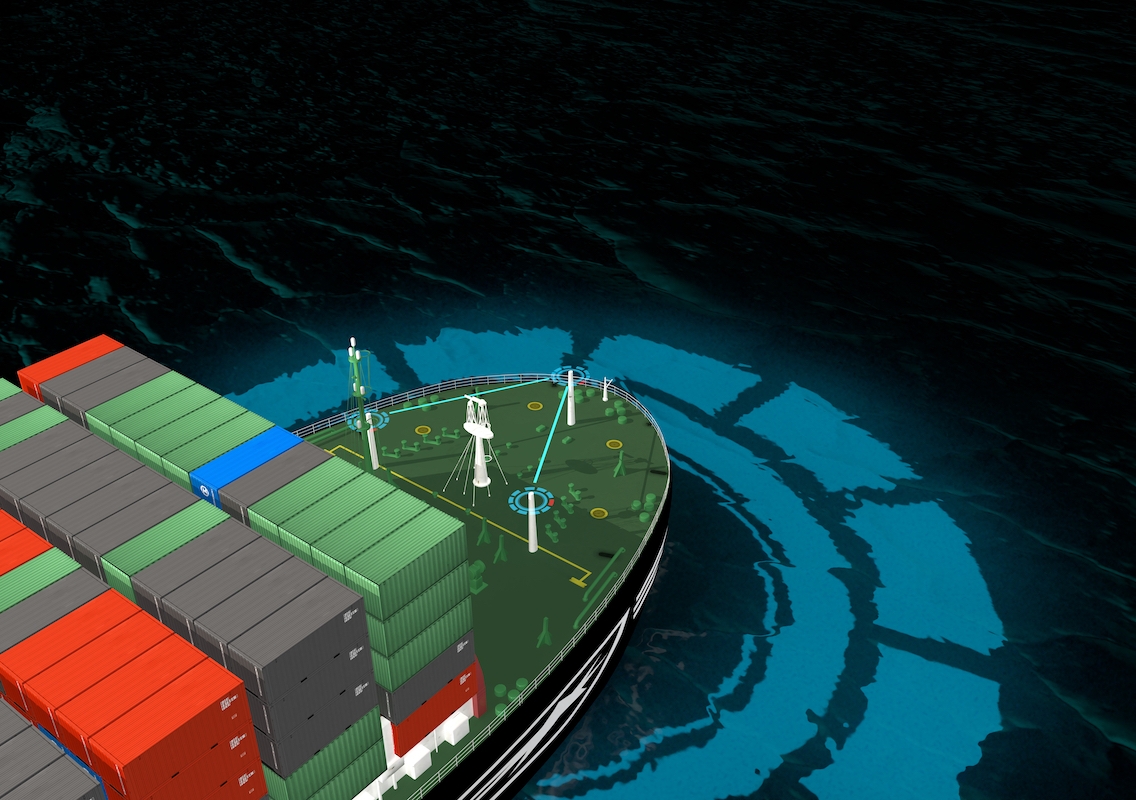

Maritime Autonomous Vehicles (MAVs) are swiftly becoming a reality. For instance, last year, a private organisation deployed an autonomous ship named the Mayflower for oceanic research purposes. Additionally, a subsidiary of Hyundai successfully executed autonomous navigation to deliver natural gas to South Korea. Over 53 organisations operate over 1,000 MAVs worldwide.

These events demonstrate the capabilities of autonomous ships, however, increasing MAV use also raises important legal questions and regulatory challenges.

Professor Natalie Klein, an expert in international maritime law at UNSW Law & Justice, is widely recognised for her expertise in maritime autonomous vehicles. As a Future Fellow of the Australian Research Council, she researches the Law of the Sea and international dispute settlement.

Prof. Klein says that the increasing use of MAVs will transform how we use the oceans, whether for shipping goods, boosting security, or safeguarding the environment through electric propulsion – a feature unique to MAVs. Electric propulsion produces less noise and pollution and consumes less fuel, reducing emissions while transporting equivalent cargo volumes.

“In each instance, we need to ensure we have the rules in place to protect rights and uphold existing responsibilities for safety and security at sea,” says Prof. Klein.

A MAV is a type of vessel or ship that operates autonomously on ocean water with minimal human intervention. There is no definition of ship, vessel or MAV in the United Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which is the main treaty governing all ocean activities.

“Discussions around the term ‘vessel’ or ‘ship’ have emerged due to differing international definitions, and ‘vehicle’ has emerged as the preferred term for MAVs instead,” says Prof. Klein.

“A vessel may be any steerable floating object that transports cargo or passengers.”

Military surveillance, scientific research, and transportation have all used MAVs.

“There has been a range of terminology used when discussing MAVs, often depending on the degree of autonomy the vehicle has. For example, we need to distinguish between remote-controlled and fully autonomous, which is relevant for data collection. We also need to determine whether a vehicle operates in combat and if it is below, on, or above the surface of the water,” says Prof. Klein.

Fully autonomous MAVs require no input from humans other than in an emergency. For remote-controlled MAVs, a person controls or monitors the vessel in real-time.

Some MAVs are small vehicles used for research and surveillance. For instance, gliders are weighted and use a pump to gently change their buoyancy over time, allowing the glider to slowly move up and down through the water.

MAVs that are larger, capable of navigation, and commonly used for transportation have the same legal rights and responsibilities as crewed vessels.

Fully autonomous MAVs require no input from humans. Photo: Shutterstock.

To ensure that MAVs are safe, efficient and have a minimal environmental impact, they deploy sensors and artificial intelligence (AI) systems onboard. These systems are responsible for navigating, steering, and avoiding collisions.

“MAVs may have humans on board occasionally – and humans are likely needed in a supervisory role on land to oversee instruments, engines, and distress calls,” says Prof. Klein.

“The duty to rescue persons or other vessels in distress still applies to MAVs, even when they don’t have any crew on board.

“In the short term, autonomous vessels may not be capable of rescuing, and they would call the closest vessel with humans onboard to assist. In the future, the design of these ships will need to consider ways to automatically send distress signals or provide information to aid in rescue efforts.

“Under international law, each search and rescue region [an area that every country manages in its surrounding oceans] has a rescue coordination centre that oversees rescues and relays real-time information to ships in the area. A MAV cannot necessarily help people in the water or have the necessary food and medical supplies on board.”

Autonomous vessels may require personnel onshore for monitoring and controlling operations, making secure communication links and constant high-volume data transfer crucial. However, increased reliance on these links may cause problems in congested waters, potentially leading to collisions. Additionally, the lack of onboard crew makes these vessels more vulnerable to cyber-attacks and criminal control, highlighting the need for proper attention to cybersecurity and communication link protection.

“To mitigate these risks, it is crucial to establish and implement comprehensive safety measures, including advanced identification protocols and robust surveillance and tracking systems,” Prof. Klein says.

In response to maritime security concerns, including the threat of cyber-attacks on ships and various crimes at sea, countries like Singapore, Japan, and South Korea are intensifying policing efforts and deploying MAVs for coastal border patrols, surveillance, mine detection, and search and rescue activities.

The focus is on preventing illegal activities such as piracy, smuggling and illegal migration.

“Manufacturers are equipping MAVs with anti-boarding measures to prevent unauthorised access and increasing surveillance to monitor vessel activity,” says Prof. Klein.

Read more: Our laws aren't ready for ‘narco-drones’ in drug trafficking

Under international law, the right of visit allows a warship to halt and examine a vessel if there is sufficient cause to suspect its involvement in piracy, human trafficking, or unauthorised broadcasting. In the future, warships may also exercise this right to stop and search MAVs if they believe they are engaged in illegal activities.

“Authorities also have the power of hot pursuit under international law, which allows them to chase and apprehend vessels in international waters that have violated their laws while within their waters,” Prof. Klein says.

Australia has rights and responsibilities regarding its adjacent waters under the UNCLOS, which defines maritime zones across all seas and oceans. Integrating autonomous vessels into the existing law is complex and needs consideration.

Autonomous vessels in Australia carry out oceanography, hydrography, offshore oil and gas work, and scientific research. For example, Austal, an Australian company, collaborates with the US and Australian Navy to increase military presence, leading a patrol boat autonomy trial in the Indo-Pacific region.

“In the coming year, we will see more multinational trials and new technology implemented, with a surge in novel solutions for commuter traffic and inland waterway transport. And future autonomous fishing vessels could help eradicate modern-day slavery in the industry,” says Prof. Klein.

Prof. Klein says it may be some time before tourists are willing to board autonomous cruise ships. However, the International Maritime Organization is working on regulatory frameworks for autonomous vehicles to ensure international law keeps up with evolving technology.

“We will need to continuously monitor how well the international law frameworks stand the test of time,” says Prof. Klein.