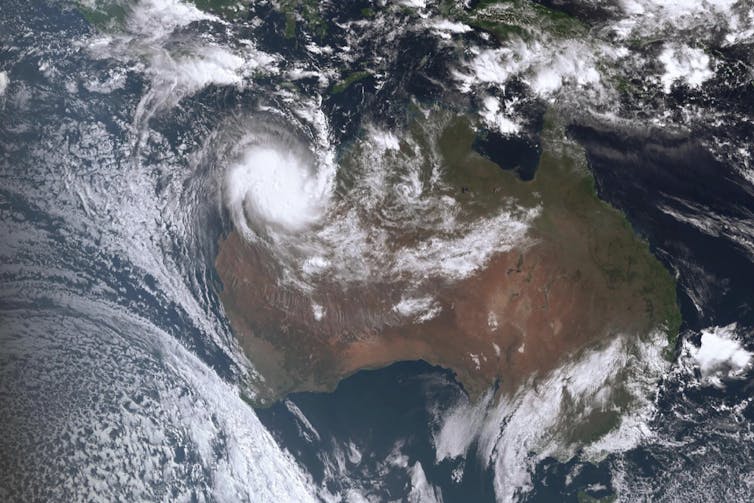

Cyclone Ilsa just broke an Australian wind speed record. An expert explains why the science behind this is so complex

Do record-breaking wind speeds mean a particularly catastrophic storm? Not always – and it can be tricky to get precise measurements.