Arts festival brings healing to a town impacted by suicide

The arts festival in Warwick, Queensland, curated by UNSW Sydney researchers, brought hope to people dealing with the devastating impact of youth suicide.

The arts festival in Warwick, Queensland, curated by UNSW Sydney researchers, brought hope to people dealing with the devastating impact of youth suicide.

Can trauma be transformed through arts-based interventions? The results are in, and the answer is yes.

In April 2022, after months of collaboration between researchers and both the local community and health care providers, members of the Warwick community gathered to take part in The Big Anxiety festival.

Trauma and suicide – particularly prevalent and devastating within the First Nations community in Warwick – were having a devastating impact on the town in regional Queensland. The high rate of youth suicide meant many people in the community had lost a son or daughter, niece or nephew, and many more had lost friends too.

The local community and healthcare providers were desperate for support to fill the gap in mental health and trauma services available.

“There is no medication for trauma,” says Prof. Bennett. “You can take medication for some symptoms, but it really needs a cultural and social response rather than just a medical one."

They sought help from the Big Anxiety Research Centre (BARC), an Australian Research Council-funded lab based at UNSW, that seeks to address mental health and wellbeing through community-based interventions. BARC’s founder director, Scientia Professor Jill Bennett, and her team published a paper ‘Transforming Trauma through an Arts Festival: A Psychosocial Case Study’ outlining the resulting collaboration and its outcomes this year.

BARC provides social and cultural responses to mental health needs, filling a gap in Australia’s mental health system noted by the Australian Productivity Commission in a report in 2020, which criticised the health system as being insufficiently people-focused with a “disproportionate focus on clinical services – overlooking [social and cultural] determinants of, and contributors to, mental health”.

“There is no medication for trauma,” says Prof. Bennet. “You can take medication for some symptoms, but it really needs a cultural and social response rather than just a medical one. Trauma is not an ‘illness’; it comes from your exposure to events, and to neglect and abuse.”

Edge of the Present – a mixed reality environment designed to cultivate future thinking in place of suicidal ideation – was presented at the Warwick Art Gallery as part of the festival program.

“Do you find life exhausting and overwhelming?” read the invitations. “Feel like there is never enough time and there must be more to life than the daily grind? If you’ve experienced trauma, loss or distress – or are just generally disillusioned by the state of the world and the hardship around us – The Big Anxiety is for you.”

The Warwick Big Anxiety program was initially centred on an exhibition at the Warwick Art Gallery named Edge of the Present – a mixed reality environment designed to cultivate future thinking in place of suicidal ideation. (Pilot work exploring its impact showed significant increases in positive mood and decrease in hopelessness.) An accompanying two-day workshop program was designed with three integrated parts:

Just two weeks before the festival was due to start, a 16-year-old First Nations young man died by suicide after visiting Warwick Hospital seeking help for his mental health. His death had a profound effect on the community, who were left feeling “angry, sad, and more hopeless”.

“We realised that this required a response,” says Prof. Bennett. “So we hosted a Long Table, which is an open community discussion, for the evening before Big Anxiety. And that built a lot of trust and allowed for a lot of issues and emotion and anger to be aired.”

It was “a fantastic opportunity to talk about mental health and suicide,” said one participant. “Suicide has been happening in this community since I was a child.”

“Out of that,” explains Prof. Bennett, “came a group within the community who were very keen to move forward and use some creative techniques to work with trauma, and intergenerational trauma, and to work collectively in the community to turn things around.”

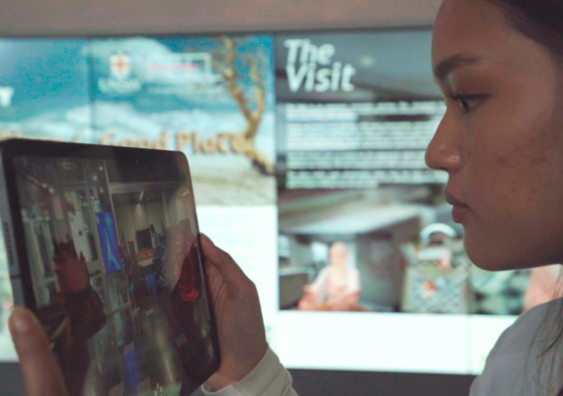

"We make tools that enable people to think about what's happening internally," says Prof. Bennett. "The arts are very sensory and can attune people to emotional states, and that can then help change, and regulate emotional states." Image: Steph Vajda.

“Creative arts experiences are resources that people can make use of,” says Prof. Bennett. “We make tools that enable people to think about what’s happening internally. It’s not that people need to do any art, it’s about using powerful creative means: images, music, stories. The arts are very sensory and can attune people to emotional states, and that can then help change, and regulate emotional states.

“Another thing creative arts can do is make people feel creative. I don’t mean that they will want to go and create a great painting, but that they feel they can be creative about their life, that they come to realise the possibilities.

“We are informed by a vast knowledge base in psychotherapy, that says if you understand your own internal process and become attuned to yourself, you can recognise what’s happening and make adjustments. That’s the goal of therapies. In many ways we are facilitating something similar outside the health framework with lots of powerful audio-visual stimuli to work with. It’s not just a little creative add-on to ‘real therapy’.

“Immersive media can drop you into an experience that might take years to even begin to articulate and then you can share that experience and really start to examine it.”

One of the workshops, Road Trip, was created by Marianne Wobcke, an Indigenous midwife and trauma worker. If you stumbled into the immersive audio-visual workshop, it might look like a music festival, with some familiar songs playing as images are projected on large screens. Using a carefully created playlist of music, Wobcke leads participants on a journey through birth/creation taking in the beautiful and the challenging, and then bringing people back to a place of peace and potential.

“My experiential workshop introduces people through relaxed, mindful awareness, to the unconscious realms of their psyche,” she said. “From birth, our perceptions program us for a life of constant struggle; alternatively with our Songline intact we may create a sense of limitless potential. We can all delight in our unique contribution to our lives, our families and greater community, inspired from a sense of abundance, wholeness, wellness and wellbeing.”

For many participants the process opens up new ways of thinking about what has happened in their lives, changing how they think about the future.

"I feel like there's been maybe 10 years of growth in a short span of time — that you would maybe not even get in a lifetime," says community organiser and festival participant Cynthia. "I feel it's really great that we've got that support coming into our community." Image: Steph Vajda.

Following the festival, participants (through surveys and/or interviews) reported a range of beneficial effects. Strikingly, these were frequently described as significant or life-altering shifts.

“Something happened in those workshops which allowed me to focus on what I need to do to heal rather than just survive,” shared one participant.

“I feel like I have gone through a journey of self-growth, but mainly self-acceptance,” offered another.

“Hope … was rebirthed in me. I feel like I discovered parts of me that were never allowed to flourish. So excited for the future.”

“This heals. It’s tailored to everyone because it’s you doing it for yourself. The gap this fills is a very big gap in the market.”

“Working with The Big Anxiety, I feel like there’s been maybe 10 years of growth in a short span of time … that you maybe wouldn’t even get in a lifetime.”

Says Prof. Bennett: “Trauma often causes us to shut down. Feeling able to take in new experiences is often the key to what we might call recovery or growth, and I think doing that in community generates a bit of passion and excitement and enthusiasm within the community.

“It’s not us doing it. It’s a collaborative sort of facilitation and then people discover their own strengths or reconnect with themselves. In fact, that’s how someone put it, ‘It’s just connected us back to ourselves and that what connects us to country and our community.’”

The BARC research team are continuing to work in Warwick. On October 21-22 they will return to host a workshop with the new virtual reality experience, Perinatal Dreaming – and to premier the film Changing Our Ways, which documents the project.

They are also working with a community in Western Australia, and communities in other regional Queensland towns to curate their own Big Anxiety programs.

“The festivals are always very adaptive and essentially community led,” says Prof. Bennett. “It’s exciting to see how our work has an impact on individuals and communities but more than that how it’s impacting the way we think about mental health services and pointing to new ways of supporting people in communities. I think that’s really going to be part of a long-term change.

“People deal with trauma and suicide in communities all the time, they don’t necessarily need a specific bunch of experts, they need some facilitation and resourcing and then they build on their strengths.”

If this story has raised issues for you, and you or someone you know needs support, please call:

In an emergency call 000 (triple zero).