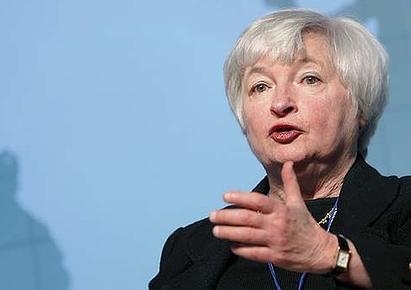

Yellen’s real-world focus a solid fit for the Fed

It is significant to have a woman at the head of the US Federal Reserve for the first time, but in terms of monetary policy it's probably business as usual. And that is a good thing for us all, writes Geoffrey Garrett.