Team provides insight into Nobel Prize winner’s polymer theory

A team of international scientists has discovered there is something missing from a Nobel Prize winner’s theory on polymers.

A team of international scientists has discovered there is something missing from a Nobel Prize winner’s theory on polymers.

A team of international scientists, including Dr Stuart Prescott from UNSW Australia, has discovered there is something missing from 1991 Nobel Prize winner French physicist Pierre-Gilles de Gennes’ theory on polymers.

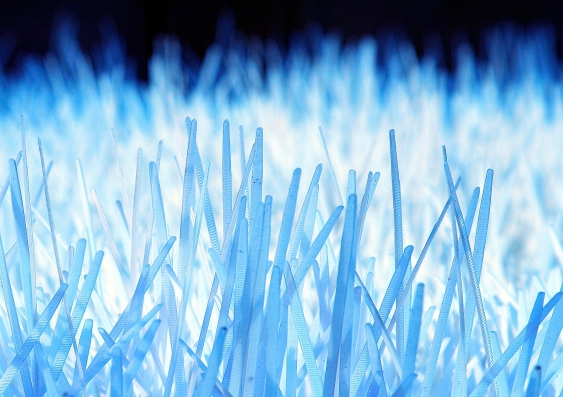

De Gennes put forward a theory that described the properties of polymer brushes, advanced polymer coatings for surfaces, and how they could be applied to surfaces as an adhesive, lubricant or as an anti-fouling agent.

Polymers are long chain-like molecules consisting of thousands of links and are widespread in consumer products, ranging from common plastics and rubbers to money and superglue. Polymer brushes are dense arrays of polymers grafted at one end to an interface to form a carpet-like structure.

But Dr Prescott’s study, published in the journal Macromolecules, found that the potential lubricating effect of polymer brushes, as put forward in de Gennes’ theory, does not fit with the available evidence.

Dr Stuart Prescott

“There's plenty of experimental evidence suggesting polymers are suitable as lubricants, however based on our data we now know the existing explanation of this is incorrect.

“The findings are quite surprising. When we realised we’d discovered there was an element missing from de Gennes’ theory it sent a real buzz through the team,” Prescott says.

“This study has changed our understanding of surface coatings and how polymer molecules behave when they are confined.”

The research was prompted by the significant gaps in the scientific literature regarding the behaviour of polymer surface structures. The UNSW-led team includes researchers in France, United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Australia.

“Before we can fully realise the potential of polymer brushes as surface coatings in commercial products, we need to fully understand how polymer brushes behave when they are manipulated,” Prescott says.

“This is what prompted us to focus on the molecular forces at play between two surfaces bearing polymer brushes.”

Using the research nuclear reactor at the Institut Laue-Langevin in France for their key experiments, the team measured what would happen to a polymer brush when it was squashed.

A polymer brush should withstand a pressure of around 100 times atmospheric pressure before collapsing, however the UNSW study showed this occurred at just one atmosphere of applied pressure.

“This tells us that there is a knowledge gap. Polymer brushes are suitable as a friction reducing coating on a surface, but we don’t know why,” Prescott says.

“While there are still plenty of gaps in our knowledge, such as understanding exactly why polymers are suitable as lubricants, we can say the science is finally catching up with the technology on polymers.”

“This research is likely to lead to better efficiency and performance of polymer products and change the way polymer-based surface coatings are designed in the future.”

Prescott and his team will continue their research using a grant from UNSW Engineering.