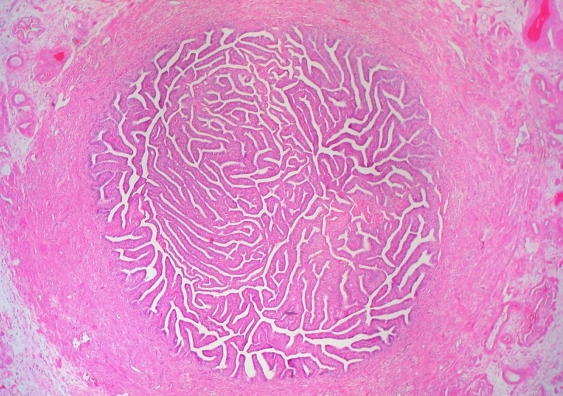

World-first fallopian tube biobank provides insights into failed pregnancies

A world-first biobank of human fallopian tube samples, established by the Royal Hospital for Women and UNSW, will give new insights into ectopic and failed pregnancies, ultimately leading to improved fertility outcomes.