Too hot in the city

Our concrete jungles are getting so hot they could eventually become uninhabitable. But a team of UNSW researchers is working hard to cool them down.

Our concrete jungles are getting so hot they could eventually become uninhabitable. But a team of UNSW researchers is working hard to cool them down.

In the middle of winter, Australians enjoy a brief respite from the crushing heat, and silently vow to better protect their homes next time summer comes around. But as more of us live in cities, there is another hurdle to overcome – the concrete jungles of our urban environment.

Nowhere is this more pronounced than in western Sydney. Deprived of the cool ocean breezes that soothe Sydney’s coastal areas, the city’s western sprawl suffers from the urban heat island effect, where dense building materials absorb more of the sun’s energy, where fewer trees provide shade, and waste heat from car engines and air conditioners intensify air temperatures.

More than 500 cities worldwide are currently dealing with this perfect storm of conditions, which has resulted in increased electricity demand, surging energy consumption in buildings, and higher mortality rates, particularly among the elderly.

It’s predicted the number of summer heatwave days experienced in some Australian cities could triple by 2050.

“Urban heat islands are the most documented phenomenon of climate change,” says UNSW Built Environment’s Professor of High Performance Architecture, Mat Santamouris, who has spent the past 15 years mapping urban heat islands in 200 cities, including a collaboration with the European Union that led to the first complete study of urban heat islands in European cities.

“The focus is often on the global impact of climate change but we also need to understand what is happening at a local level, in our own cities,” says Santamouris. “If we can’t find a way to make our cities cooler, they will eventually become uninhabitable.”

Formerly the Director of the Laboratory of Building Energy Research at the University of Athens, Santamouris has brought his expertise to major heat-mapping projects in Australia as UNSW’s inaugural Anita Lawrence Chair in High Performance Architecture.

After analysing data from six weather stations across a 10-year period in the Greater Sydney Area, he describes western Sydney as “a catastrophic scenario waiting to happen”.

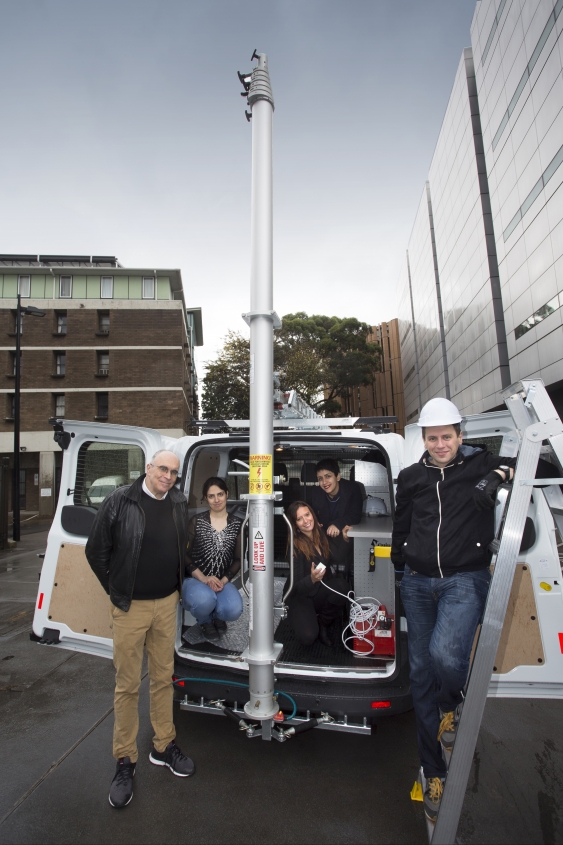

Professor Santamouris with his team and the Energy Bus. Photo: Quentin Jones

“It's hard to remember that kind of heat when we’re in the middle of winter, but last summer the temperature in Penrith was above 40 degrees Celsius for about 20 days, reaching even 46 degrees Celsius. It was unbelievable.

“That is on average, eight to nine degrees Celsius higher than the medical risk threshold. People were really suffering, and most people in these areas can’t afford air conditioning.”

He recalls the 2003 heatwave in Europe that resulted in more than 50,000 deaths and the power failure during Adelaide’s heatwave this year, saying electricity demand in our already over-heated cities could cause these situations to happen more frequently.

However, Santamouris prefers to focus on the solution rather than the problem. As the former president of Greece’s national body for the promotion of renewable energy sources and conservation, he has plenty of experience.

“It is critical that we turn the urban heat island challenge into an opportunity, by working out how it can benefit the economy. Focusing on the negative impacts doesn’t help, we need to find a better solution.”

Much of his research involves developing heat-mitigation technologies to help cool our cities in the future. “Reflective materials on buildings can help reduce the urban heat island effect, as can cooling pavement technologies, street shading, greenery and installing fountains, ponds and sprinklers,” he says.

“But there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Every city has its own set of issues so we often need to use a cocktail of different solutions.”

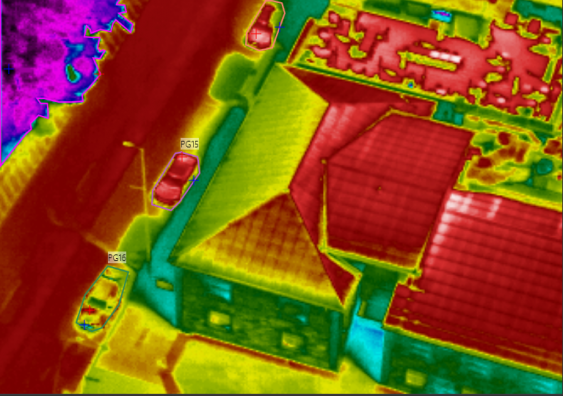

Santamouris and his team use a mobile lab called the Energy Bus to record the scientific data they collate when mapping urban heat islands. The bus, combined with the thermal imaging provided by an accompanying drone, allows data to be visualised and transmitted in real time via a 20m extendable aerial.

The Energy Bus, the first of its kind in Australia, was used in Santamouris’s latest project which aims to reduce the temperature in Darwin’s CBD by three degrees.

Funded with $100 million by the Northern Territory government, and an equal budget by the Commonwealth Government, Santamouris says the Darwin project is the largest heat-mitigation study in the world. Using thermal imaging and drone aerial monitoring to map the city’s hotspots, the team has recommended ways to retrofit the entire CBD to achieve the maximum cooling effect.

Shading, cool roofs and new-generation, cool pavements that absorb less solar radiation, green roofs (where vegetation is planted on rooftops to absorb carbon dioxide and pollutants) and water sprinkling (where a light mist is sprayed directly into the air and then descends) have all been recommended.

But Santamouris is acutely aware that new heat-mitigation technologies need to be developed quickly.

“The goal now is to develop heat-mitigation materials and solutions capable of reducing urban temperatures by five degrees.”

“When I started my research 15 years ago the aim was to reduce urban temperatures by 2.5 degrees Celsius but now we’re running to catch up. The goal now is to develop heat- mitigation solutions capable of reducing urban temperatures by five degrees, and in the case of western Sydney it needs to be by seven degrees.”

Santamouris isn’t just racing against the global warming clock, he’s also committed to educating the local community about the impacts of climate change while there’s still time to make a change. “We need to initiate people into the problem of climate change, and get them involved,” he says. “That has far more influence than an expert telling them.”

As part of a university collaboration with RMIT, Santamouris and his team have been successful in the Citizen Science Grants scheme run by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science as part of the National Innovation and Science Agenda.

The project, which is worth $670,000, will allow Santamouris and his team to work with 12,200 residents from 22 local councils across Australia, by providing them with the technology to measure the thermal performance of their neighbourhoods.

“This is the first large-scale project in the world to involve people in the understanding of heat mitigation,” Santamouris says.

As part of the two-year study, citizen scientists will use portable wireless sensors to measure temperature, humidity, wind and solar radiation in 2,200 areas across 22 councils in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane, the Gold Coast, Canberra, Darwin and Perth.

“People understand climate change in that it’s an increase in temperature, but they don’t know how it personally affects their neighbourhood, their home and their life. For example, if they plant a tree how does that lower the temperature of their house?” he says.

In the final stage of the project, participants will be taught how to design heat-mitigation techniques to cool their homes.

Santamouris says UNSW is at the forefront of developing heat-mitigation techniques that will make our cities more livable, protect vulnerable populations and save lives.

“Urban overheating is perhaps among the more severe climatic phenomena that humanity faces, but I’m confident that in a three- to five-year period, we will be able to decrease peak ambient temperatures by up to four or five degrees Celsius.”