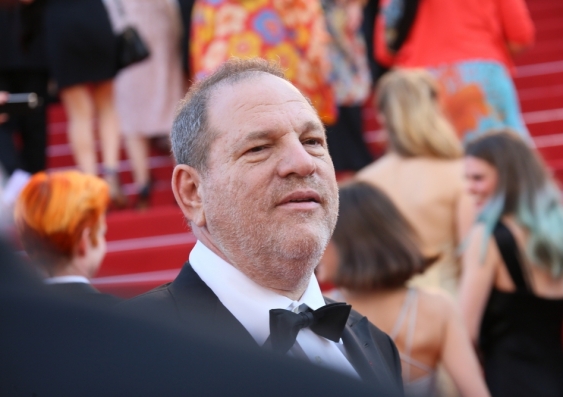

What the Harvey Weinstein case tells us about sexual assault disclosure

The power disparity between Harvey Weinstein and his alleged victims plays into a range of myths and stereotypes about women, writes Bianca Fileborn.

The power disparity between Harvey Weinstein and his alleged victims plays into a range of myths and stereotypes about women, writes Bianca Fileborn.

Explosive reports from The New York Times and The New Yorker in recent days have revealed decades of alleged sexual harassment and assault perpetrated by high-profile Hollywood movie executive Harvey Weinstein. In the wake of these reports, a flood of disclosures from celebrities, including Angelina Jolie and Gwyneth Paltrow, has emerged.

The Weinstein case follows an emerging pattern of powerful men being outed for their sexually violent behaviour. In such cases, men have been able to abuse with relative impunity, despite many in the entertainment industry appearing to know or have suspicion of their behaviour.

These instances raise several pertinent questions about sexual violence and harassment. They include:

why it’s so difficult for victim-survivors to come forward;

why they aren’t believed when they do;

why we tend to see a flood of reporting once the case is broken;

how men such as Weinstein are able to offend with impunity for so long; and

most importantly, what we can do to prevent such cases from reoccurring.

Victim-survivors face a wide range of barriers to disclosing their experiences, regardless of the context in which the assault occurred. Commonly identified barriers include:

fear of not being believed;

fear that their experience will be dismissed or trivialised;

belief that the incident wasn’t “serious” enough to tell anyone about;

fear of retaliation from the perpetrator;

believing there was nothing that could be done about it;

wanting to move on from or forget the incident;

confusion about what happened;

shock; and

self-blame.

Many barriers are heavily informed by misconceptions and stereotypes about sexual violence. The narrow framing of “real” rape as involving extreme violence or physical force and penetrative sex, or that the perpetrator is a stranger, can prevent victim-survivors from speaking out or even identifying and labelling their experience as sexual violence in the first place.

Although victim-survivors face substantial barriers to disclosure, most eventually tell somebody about their experience. How that person reacts can be vital in informing what happens next.

Positive responses, such as an expression of belief and validation, can aid in recovery and encourage further disclosure and reporting to authorities. Negative responses, such as blaming the victim or disbelief, can shut down any further discussion or disclosure.

All forms of sexual violence feature an imbalance of power. This is heightened in Weinstein’s case. As a high-ranking Hollywood producer, he was often in direct control of the careers of his victims, many of whom were young women.

It is reasonable to assume that many did not disclose for fear of losing their careers, or otherwise facing the wrath of a well-connected, wealthy and powerful man. Weinstein’s position enabled him to reportedly buy the silence of several victims.

However, this is not to say these women did or said nothing in response to Weinstein’s actions. It appears his behaviour was an open secret among women in Hollywood, who warned each other about him.

Rather than not disclosing, it would seem that Weinstein’s victims were selective about who they told. Their disclosure practices sought to protect other women, rather than openly exposing their perpetrator.

The power disparity between Weinstein and his victims plays into a range of myths and stereotypes about women. Namely, there is a myth that women routinely lie about sexual assault as a form of revenge or – in the case of wealthy perpetrators – as a means of “gold-digging”, attention-seeking, or advancing their own status.

These myths are not borne out in the substantial research evidence on sexual violence. False reporting is rare. Victim-survivors are often blamed for their own experiences, routinely dismissed or disbelieved, and the criminal justice system is commonly encountered as a site of retraumatisation.

It is difficult to conceive what benefit victim-survivors may garner from “false” disclosure in such circumstances. And perpetrators in a position of such cultural and economic power can overtly exploit this to facilitate and enable their offending with relative impunity.

Research has illustrated how perpetrators draw on their position to silence victims, often by reinforcing the notion that no-one will believe them if they do disclose, or by threatening to destroy their reputation or livelihood.

Under these circumstances, it is unsurprising that many of Weinstein’s victims did not disclose widely earlier. It is equally unsurprising that the initial media reports have sparked a flood of disclosures from women who Weinstein targeted.

In taking women’s experiences seriously, this reporting – and the subsequent public outcry – has opened up a space for other women to disclose. It signifies to these women that they will be believed and taken seriously, with the weight of collective disclosure making it more difficult for their experiences to be dismissed or downplayed.

Given that Weinstein’s actions were an open secret for so long, this also raises questions of how he was able to continue offending with impunity.

Weinstein’s position of power played a key role here, and ensured that many of his victims were effectively silenced. However, it is also apparent that others within the industry condoned or at least tolerated his behaviour. It is vital that we imbue bystanders with the confidence and skills to intervene.

Weinstein’s actions were further enabled by a cultural context that normalised abusive behaviour through references to the “casting couch” and stereotypes of the lecherous industry figure who “takes advantage” of young actresses as a matter of course.

Such attitudes normalise and rationalise the occurrence of sexual harassment and assault, reframing it as acceptable. This can prevent potential bystanders from stepping in, and obscures the problematic nature of such behaviour. It is vital that we work to disrupt and challenge cultures that normalise sexual violence.

Finally, we must ensure women are able to disclose their experiences without fear of disbelief, blame or dismissal. Such systematic and widespread abuse might be avoided if only we were willing to believe women, and listen when they do disclose.

Finally, we must ensure women are able to disclose their experiences without fear of disbelief, blame or dismissal. Such systematic and widespread abuse might be avoided if only we were willing to believe women, and listen when they do disclose.

Bianca Fileborn is Lecturer in Criminology at UNSW. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.