Chinese students must be welcome in Australia

Recent commentary about China's engagement with Australia's universities has overlooked the enormous benefits our academic links with China generate, write David Gonski and Ian Jacobs.

Recent commentary about China's engagement with Australia's universities has overlooked the enormous benefits our academic links with China generate, write David Gonski and Ian Jacobs.

OPINION: A powerful China is here to stay. The government’s foreign policy white paper makes that point firmly while also positing that China’s continuing rise means friction is all but inevitable – against the backdrop of the US being encouraged to remain active in Australia’s back yard.

These are complex waters to navigate and, as Paul Kelly so rightly pointed out in The Australian on Wednesday, the underlying issues demand a vigorous debate on our values and Australia’s opportunities and risks.

In the white paper, education again emerges as a shining light. The nation’s third largest export earner is positioned at the heart of our foreign policy agenda – somewhat overlooked in the aftermath of the white paper’s release.

This is significant because much of the recent debate may have sullied the reputation and critical importance of international educational links, with allegations of international students driving sinister Communist Party agendas and undermining our independent universities.

Suddenly Canberra has placed education in its rightful place as a serious foreign policy tool for Australia to shape the future of our region and build economic bridges to drive our nation’s prosperity and ties with Asia’s 21st-century superpowers.

While much debate has been about facts, some recent commentary about China’s engagement with Australia’s universities has been sensationalist, and this saddens us.

It has overlooked the enormous benefits that our academic links with China generate.

First, an important group of people in this story are the millions of Chinese students who have invested their trust, and their money, in an Australian education since the first students arrived in the 1980s.

Most of them return to China to pursue their careers with an understanding of Australian culture and society, along with a fondness for the university they attended and our country.

A UNSW Sydney delegation met many alumni during a recent visit to Shanghai and Beijing and was impressed by the positions they held in finance, management, arts, manufacturing and academe, their affection for Australia, and the opportunities created for UNSW in China.

Second, based on the foundation of many years of educational interactions and the mutual understanding and respect that brings, our universities are now able to partner with Chinese businesses to generate economic benefit for both nations.

To cite just one example, UNSW has partnered with China’s Torch Program, an organisation that has established almost 150 science parks across China, generating an astonishing 13% of the gross domestic product of the world’s second largest economy.

The choice of suitable Chinese partners is important and UNSW and other universities do this with substantial due diligence as well as reference to the federal government’s probity requirements and defence trade controls.

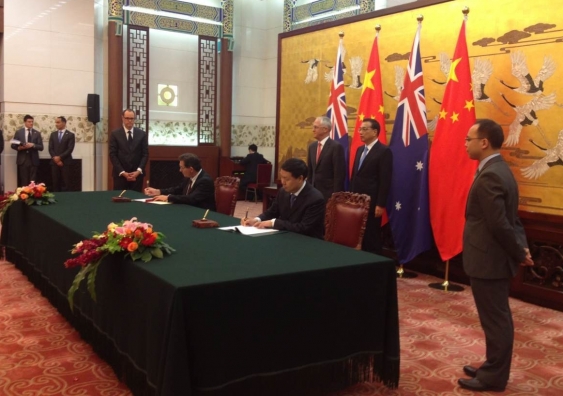

Since last year’s signing of the UNSW-Torch memorandum of understanding, which was witnessed by Malcolm Turnbull and Premier Li Keqiang, this venture has led to business contracts worth more than $80 million. These provide a platform to commercialise technology in health, energy and environmental protection, with shared financial rewards for Australia and China. Other universities have similar ventures.

To suggest that these partnerships provide open, endless opportunities for the foreign partner to “spy” and freely take intellectual property ignores the care that has been taken to provide safeguards in this regard and the nature of these partnerships.

The choice of suitable Chinese partners is important and UNSW and other universities do this with substantial due diligence as well as reference to the federal government’s probity requirements and defence trade controls.

Third, given the complexities of international interactions, the dangers of increasing nationalism and the risks specific to the Asian continent, there is great value in Australian academics and students developing strong relationships with present and future university, business and government leaders in China. The benefits of genuine, established personal relationships, particularly at times of crisis, should not be underestimated.

Rather than making sensational claims about China’s engagement with us, we should emphasise the duty of care Australian universities have for every one of their students, including international students and the 108,260 Chinese students studying here.

We’re proud of our Chinese students and committed to providing them with a safe, high-quality and fulfilling experience. That requires continuing attention to safety, enhancing support for Chinese students to improve their English proficiency, and to facilitate their positive interactions with students from Australia and elsewhere.

Australia’s bilateral relationship with China is complex, dynamic and at times challenging. We rely heavily on China as the world’s economic engine and on trade with China for economic prosperity. China is Australia’s largest two-way trading partner in goods and services and our largest export market, in which Australian education exports are worth $21.8 billion. On the other hand, there are concerns about the rise of the single-party state as a global superpower.

We have much to gain from fostering closer, authentic relationships with the Chinese students we host. The goodwill, understanding and appreciation of Australia’s political and education system this fosters endures as today’s students move into positions of influence back in China.

The alternative risks taking us down a dark road. Misinformed, biased and inflammatory public debate fans violence and bigotry. All of this is quite apart from the reality of the decency, friendliness and ability that we have observed in our Chinese students.

In the meantime, China’s power and the critical importance to Australia of a workable bilateral relationship will not wane.

David Gonski is Chancellor of UNSW. Professor Ian Jacobs is President and Vice-Chancellor of UNSW.

This article was originally published in The Australian.