Can art really make a difference?

Artists have long tackled global issues, from war to human rights. But what, asks Joanna Mendelssohn, does this actually achieve?

Artists have long tackled global issues, from war to human rights. But what, asks Joanna Mendelssohn, does this actually achieve?

In 1936 Karl Hofer painted the work that best encapsulates the dilemma of German artists in the first half of the 20th century. Kassandra is a bleak vision of the prophetess of Ancient Troy, doomed always to foresee the future, and doomed never to be believed. In 2009 it was exhibited in Kassandra: Visionen des Unheils 1914-1945 (Cassandra: Visions of Catastrophe 1914-1945) at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin and its message has haunted me since.

The exhibition included some of the best of German art from the 1920s, when many intellectuals, especially those working in the arts, foresaw the extent of the Nazi nightmare that would become the new normal. Some recognised what they were seeing and left the country. The majority experienced the consequences of disbelief. British comedian Peter Cook’s cutting remark on “those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the second world war” is often quoted as proof that art is a futile commentary in the face of rising tyranny.

And yet artists persist in challenging assumed knowledge in their attempts to awaken the conscience of the world. Artists can become witnesses for the prosecution of the crimes of our times, as well as enabling some viewers to see the world differently.

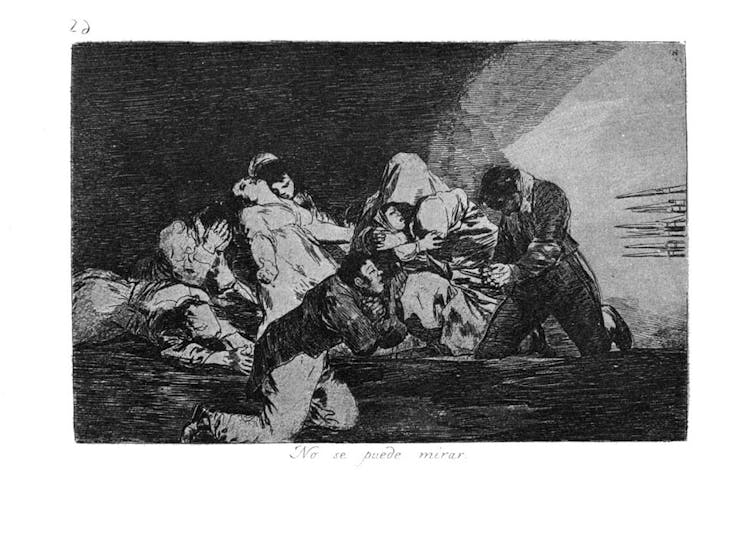

Before the early 19th century, war was most commonly depicted as a heroic venture, while death was both noble and surprisingly bloodless. Then came Goya with his Disasters of War to show the full horror of what Napoleon inflicted on Spain. The art showed, for the first time, the suffering of individuals in the face of military power. After Goya war could never be seen as a truly heroic venture.

A century later Otto Dix, who volunteered for the First World War and was awarded an Iron Cross for his service on the Western Front, was loathed by the Nazis for his 1924 suite of etchings, Der Krieg (The War). Consciously working in the tradition of Goya, he drew the most intense evocations of the full horrors of his experiences in the muddy bloody trenches where madmen roamed and poppies bloomed from the skulls of the dead.

Dix’s harsh realism was incompatible with any propaganda about death as glory. His 1923 painting, Die Trench (destroyed during the Second World War), was immediately condemned by the Nazi Party as art that “weakens the necessary inner war-readiness of the people”. A Cassandra indeed.

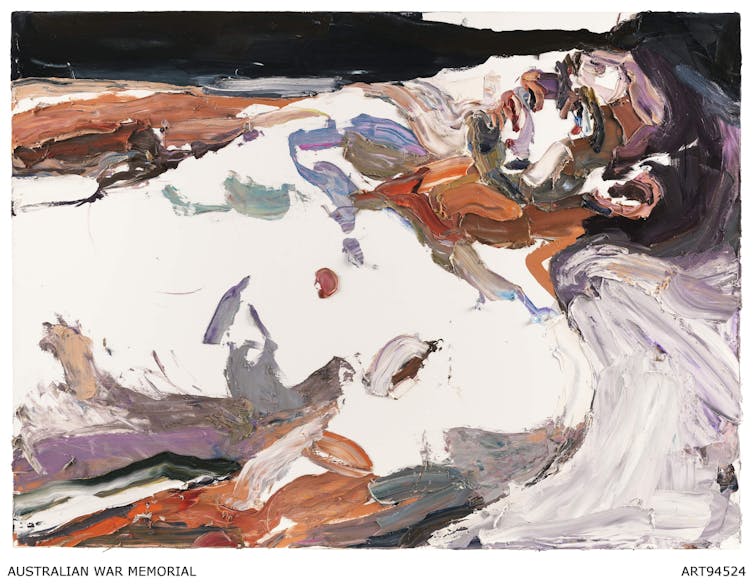

The intensity of Dix’s response to that first terrible conflict of the 20th century has become an inspiration for more recent art about war and its consequences, including that of Ben Quilty and George Gittoes. Quilty’s After Afghanistan series, which came from his work as Australia’s official war artist, presents the ongoing trauma of soldiers returned from the ongoing act of military futility.

Both Quilty’s and Gittoes’ art encourages empathy with individuals caught in war, but in no way challenges the policies that lead to violent conflict. The Australian Army still upholds our national tradition of fighting in other people’s military adventures.

The futility of art as a weapon of protest seems to be borne out by that most famous anti-war painting of them all, Picasso’s Guernica, painted for the Spanish Pavilion of the Paris World Fair 1937. On April 26, 1937, German and Italian forces bombed the Basque town of Gernika in support of the Fascist General Franco’s conquest of Spain. Guernica was painted with the full force of raw grief, by an artist who was well aware that he was working in the polemic tradition of Goya and Dix.

Its huge scale, drawn with passionate line and painted with deliberate thin ragged paint in black, white and grey to honour the newsprint that first told the tale, means that even now, over 80 years after it was painted, it still has the capacity to shock.

In 1938, in an effort to raise funds for the Spanish cause, Guernica toured Britain where, in Manchester, it was nailed to the wall of a disused car showroom. Thousands flocked to see it, but to no avail. The British government refused to intervene. In 1939 the victorious Franco gave Spain a Fascist regime that only fully ended with his death in 1975.

In the years after World War II mass reproductions of Guernica with its strong anti-war message hung in schoolrooms around the world. Those who saw it were a part of the generation who saw the United States bomb Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

The great crisis of our times, human-caused climate change, has already played a role in wars and famine alongside the usual social and political factors. The effect of these disasters has been a global mass migration of refugees. This diaspora is one of the themes of the current Biennale of Sydney.

Three of the seven locations at the biennale are dominated by the work of Ai Weiwei, who in recent years has turned from using his iconoclastic aesthetic to expose corruption within China to the global distress of millions. His giant sculpture, Law of the Journey, evokes the many rafts that are beached on the shores of the Mediterranean. Some carry their human cargo to unwelcoming hosts, others foundered on the way. Many drown trying to escape to some kind of future. Ai Weiwei has placed an inflated crowd of anonymous refugees into his giant boat, so that the viewer gets a sense of the enormity of it all.

While it fits so well in the cavernous space of the Powerhouse on Cockatoo Island, Law of the Journey was originally a site-specific work for the National Gallery of Prague in Czechoslovakia, a country that once sent refugees to the world and now declines to receive them. Around the base of the boat are inscriptions commenting on the attitudes that have led to this international tragedy. They range from Carlos Fuentes’ plea to “recognise yourself in he and she who are not like you and me”, to the Czech literary and political hero Václav Havel.

From 1979 to 1982, when he was in prison, Havel wrote letters to his wife, Olga. Because of the terms of his imprisonment these could not be overtly polemical. Nevertheless he wrote a remarkable commentary on the nature of modern humanity, which was later published. His observation, “The tragedy of modern man is not that he knows less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothers him less and less”, is appropriately placed here.

There is a sense of ambiguity in what is really a companion piece, located in the intimacy of Artspace. A giant crystal ball rests on a bed of faded life-jackets, discarded on the shores of Lesbos. It implies that the world is at the crossroads. Governments and people must decide which direction to follow in a time of crisis.

Ai Weiwei’s film Human Flow presents that crisis in a way that cannot be denied. Its first Australian screening at the Sydney Opera House was a part of the Biennale of Sydney’s opening festivities, but it is now distributed for general release. It is both overwhelming in its impact and deliberately internally contradictory.

There are sweeping beautiful vistas of a tranquil Mediterranean Sea – that then zoom in on a rubber boat overfilled with orange life-jacketed figures, all risking their lives to go to a dream of Europe. As people are helped ashore on the rocky beaches of Lesbos, one passenger tells of boats following and his fear that they will not arrive because of the rocks. So many die at sea. There is terrible beauty in the billowing smoke of the burning oil fields that ISIS left as their legacy in Mosul, and magnificent dust storms filmed in Africa where climatic changes continue to drive many from their lands.

For Australians, there are echoes of the cruelty of our government in the attitudes and actions of the governments of Macedonia, France, Israel, Hungary and the USA. The film argues that today there are approximately 65 million refugees, most of whom will spend over 20 years without a permanent home. The great humanitarian project of post-World War II Europe, that gave a future for its refugees, has ended with barbed wire, tear gas and drownings at sea.

We are at one of those times in human history where the simplistic answer to a problem only creates disaster. Turning people back at borders or returning them to an unsafe home creates another long march, or more drownings. Creating an army of young men without hope is a recipe for recruitment for ISIS and their successors. People who see a future for themselves and their children are less likely to become suicide bombers.

Human Flow argues that ultimately the responsibility for the problem (and the solution) for refugees lies with those presidents and parliaments who see no need to adapt to the changing world.

This art will not change Australia’s inhuman policies towards asylum seekers. On the night of the Sydney Opera House premiere, Ben Quilty asked Ai Weiwei if he felt that his film might make a difference. His answer was: “For a very short moment, maybe.”

The ultimate value of Human Flow is as a witness statement if ever governments are called to account for their folly. Ai Weiwei has gathered material to show a mass audience that he has the evidence to convict our times of gross neglect of humanity. He is a modern Cassandra, telling truth to power through art. The powerful then admire his art’s aesthetic qualities while placing it in the official art collections of all those countries that prefer not to see what he is trying to say.

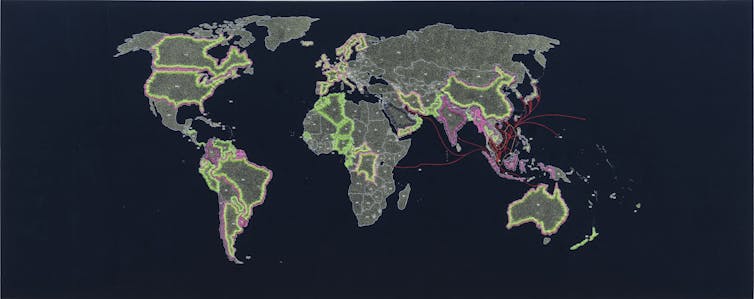

Other artists in the Biennale take a slightly different and perhaps more subtle approach. Tiffany Chung, who left Vietnam as a refugee in the great exodus of the 1970s, is also exhibiting at Artspace. Her meticulous embroidery of a map of the world charts the routes of the boat people from Vietnam and Cambodia, while accompanying documentation shows how they were received with the same level of suspicion that greets today’s refugees.

Chung’s current homes in both the US and Vietnam are a reminder that those countries that do open their hearts to refugees can benefit from their presence, and that, in time, many conflicts end in reconciliation. It is asking too much of art to expect it to change government policies or human destiny, because the experience of seeing art is so individual. It is possible that art can change people’s attitudes to life, but this is more likely to happen on an individual basis.

In a large tin shed, high on Cockatoo Island, Khaled Sabsabi’s installation Bring the Silence continues a trajectory he began long ago – honouring the creative tradition of Sufism and using it as a pathway between cultures. Even before entering the shed, the visitor notices the enticing perfume of rose petals. Inside the dark, the luscious smell is almost overwhelming, while the floor is covered with carpets sourced from that home of all that is good in Middle Eastern shopping, Auburn in Sydney’s western suburbs. The viewer is surrounded by the softened chatter of street noise while being seduced by the intensity of colour from the giant suspended screens and the smell of roses.

Bring the Silence is an eight-channel video with each screen showing a different view of a Delhi tomb, the shrine of the great Sufi saint, Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya. Some men are casting rose petals and brightly coloured silk cloths onto the mound that contains his body, while others pray. Women and unbelievers are not allowed in this sacred space; Sabsabi had to ask special permission to film. Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya was one of the most generous of medieval saints who saw that a love of God led to a love of humanity, and spiritual devotion combined with kindness.

Sabsabi has spent many years exploring this most joyous of all Islamic traditions. To those in his home in Sydney’s western suburbs, he shows how art can cross cultural barriers between Muslim and non-Muslim Australians. For non-Muslims, he provides a window into an aspect of Islam that is both creative and mystical, as well as more accepting than the image of faith regularly denounced by the shock jocks.

That same visual advocacy is why it is no surprise to find Sabsabi is exhibiting in Adelaide at Waqt al-tagheer: Time of change. The artists, who call themselves eleven, represent the diversity of Islamic Australia as they challenge stereotypes through the variety of their art. Their exhibition strategy is modelled on that of the very successful Aboriginal collective ProppaNOW, which for the past 15 years has collaborated to project the concerns and art of urban Aboriginal people. Their subsequent success as artists has been both individual and collective. Just as importantly they have overseen a shift in attitudes as to what an Aboriginal person may be.

Transformation through art is not just about objects. In Tasmania, David Walsh’s eccentric creation of MONA has been credited as the most important element in the revival of that state’s fortunes. It is not the only reason – green islands in temperate climates are increasingly attractive as the world warms – but even the most cynical will admit the changes he has wrought through art.

![]() The changes art and its practitioners make are not instant. Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton will not reverse his attitude to refugees as a result of seeing Human Flow. But he is not necessarily the target audience. Ai Weiwei has written: “Art is a social practice that helps people to locate their truth.” Maybe that is all we can ask of it.

The changes art and its practitioners make are not instant. Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton will not reverse his attitude to refugees as a result of seeing Human Flow. But he is not necessarily the target audience. Ai Weiwei has written: “Art is a social practice that helps people to locate their truth.” Maybe that is all we can ask of it.

Joanna Mendelssohn is Honorary Associate Professor, Art & Design, UNSW Australia and Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, UNSW.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.