Recycling goes to landfill while technology sits idle

People are losing confidence in recycling and overwhelmingly want government to support solutions such as UNSW's groundbreaking microfactory technology, a new survey shows.

People are losing confidence in recycling and overwhelmingly want government to support solutions such as UNSW's groundbreaking microfactory technology, a new survey shows.

Stuart Snell

0416 650 906

s.snell@unsw.edu.au

The effectiveness of recycling services across Australia is being seriously questioned as new research shines a critical light on waste management efforts.

The findings of the first of a series of surveys by UNSW Sydney to better understand community attitudes to important issues, come as the growing waste problem around Australia and globally intensifies after a ban in January by China on accepting certain recyclable materials it had been taking from other countries.

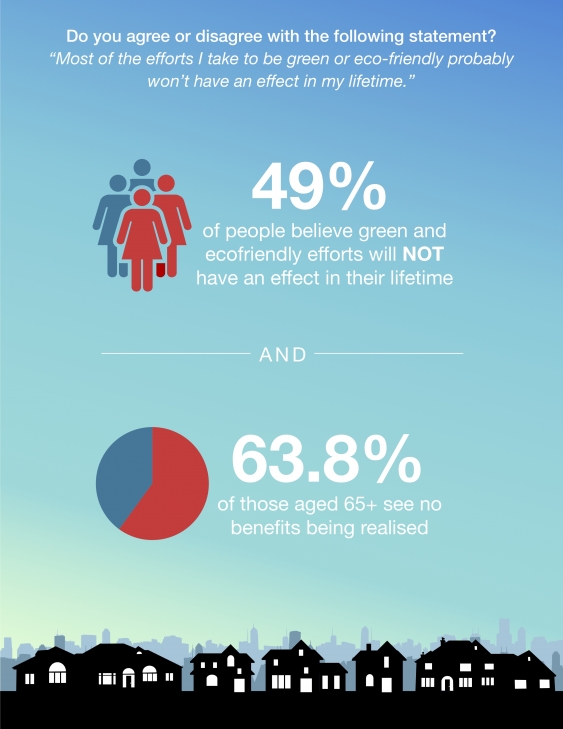

Most people, across all states and demographics, believe the recyclables they put out in their council bins are ending up in landfill.

Professor Veena Sahajwalla, Director of UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) Centre, said rising stockpiles and increasing use of landfill – in the absence of a coordinated government solution to our growing waste problem – had not been lost on consumers and they wanted action.

“Each council is fending for themselves right across Australia and while the meeting of federal and state environment ministers earlier this year made an important announcement about a new National Waste Policy, stating that by 2025 all packaging will be re-usable, compostable or recyclable, we don’t have to wait another seven years for this decision to come into effect,” Professor Sahajwalla said.

“There is much that can be done right now given that scientifically-developed and proven methods are currently available through the green microfactory technology, yet the federal government is now also pushing on with an investment of $200 million into so called ‘waste to energy’ projects that actually destroy forever waste materials that can be used over and over as a renewable resource.”

Key findings show:

People are also confused about which levels of government – local, state, federal, or all three – are responsible for their local waste and recycling services. In fact, some people think industry, not government, is responsible for waste management.

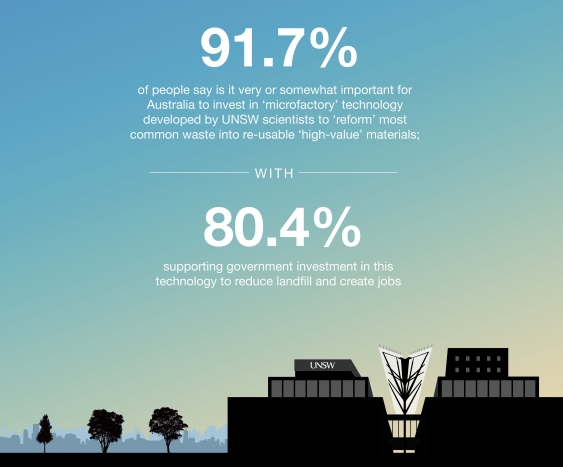

But what is overwhelming is the Australian public’s determination for our governments to do much more to better manage recycling and investment into technology such as microfactories.

91.7% of people say is it very or somewhat important for Australia to invest in microfactory technology to ‘reform’ most common waste into re-usable ‘high-value’ materials, and 80.4% support government investment in this technology to reduce landfill and create jobs.

“It is clear on this issue that people want action, and they want governments to invest and do something now,” Professor Sahajwalla said. “A number of councils and private business are interested in our technology but unless there are incentives in place, Australia will be slow to capitalise on the potential to lead the world in reforming our waste into something valuable and reusable.

“Rather than export our rubbish overseas and to do more land fill for waste, the microfactory technology has the potential for us to export valuable materials and newly manufactured products instead. Through the microfactory technology, we can enhance our economy and be part of the global supply chain by supplying more valuable materials around the world and stimulating manufacturing innovation in Australia.”

Gabrielle Upton, NSW Minister for the Environment and Professor Veena Sahajwalla at the launch of the world’s first e-waste microfactory. Photo: Quentin Jones.

The NSW Environment Minister Gabrielle Upton launched the world’s first demonstration e-waste microfactory in April this year. This showcases a process developed by the UNSW SMaRT Centre, which transforms the components of discarded electronic items like mobile phones, laptops and printers into new and reusable materials that can then be used to manufacture high value products. There is no need to dump this e-waste, when it can be used to produce high value metal alloys, carbon and products such as 3D printer filament.

UNSW is also finalising a second demonstration microfactory, which converts glass, plastics and other waste materials into high value products. Mixed waste glass is used to create engineered stone products, which look and perform as well as expensive marble and granite. Wood, plastic and textile waste is used to create valuable insulation and building panels.

Our e-waste microfactory involves a number of small machines for this process and they fit into a small room. The discarded electronic devices and items are first placed into a module to break them down. The next module may involve a special robot to extract useful parts. Another module uses a small furnace to separate the metallic parts into valuable materials, while another one reforms the plastic into filament suitable for 3D printing.

A microfactory can involve one or a series of modular machines and be easily transported or relocated to where a stockpile or suitable site exists. Costings show an investment in some microfactory modules can pay off in less than three years. Glass stockpiles alone amount to more than one million tonnes per year nationally. In total, Australia produces nearly 65 million tonnes of industrial and domestic solid waste each year, but it is now cheaper to import than recycle glass here. About 60 per cent of waste is reportedly recycled but much of this is low value.

“Our new recycling and reforming process via what we call a microfactory has the potential to deliver economic and environmental benefits wherever waste is stockpiled,” Professor Sahajwalla said. “The main impediment to deploying these new methods is the lack of incentive by governments for industry to adopt them.”

Professor Sahajwalla said green microfactories can not only produce high performance materials and products, they eliminate the necessity of expensive machinery, save on the extraction from the environment of yet more natural materials, and reduce the impact of burning waste and dumping it in landfill.

UNSW, through its ARC Green Manufacturing Hub, has developed this technology with support from the Australian Research Council and is in partnership with several businesses and organisations including recycler TES and manufacturer MolyCop. And through the Commonwealth funded CRC-P initiative, SMaRT is partnering with Dresden, which makes spectacles, in the use of recycled plastics.

Audio, images and vision: Infographics, broadcast quality grabs and video by Professor Sahajwalla as well as photos of the e-waste microfactory in our laboratory and the full poll results are available via this link or the contact listed below.

Media contact: Stuart Snell, UNSW External Communications, 0416 650 906 s.snell@unsw.edu.au.