Myth busted: China’s status as a developing country gives it few benefits in the World Trade Organisation

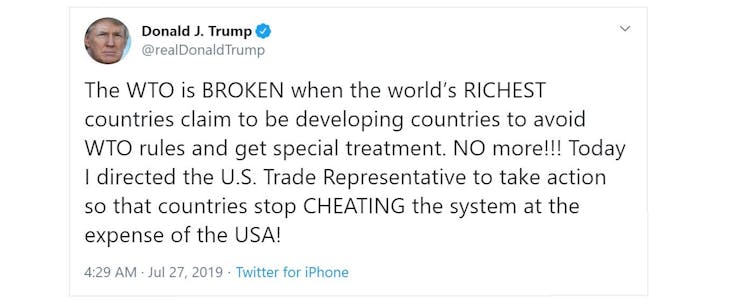

In complaining about China's alleged special treatment by the World Trade Organization, US President Donald Trump and Australia's Scott Morrison are pointing to something that isn't really there.