What history can teach us about pandemic management

How do responses to infectious diseases throughout history stack up today?

How do responses to infectious diseases throughout history stack up today?

Ben Knight

UNSW Media & Content

(02) 9065 4915

b.knight@unsw.edu.au

While the word unprecedented has become part of the rhetoric around COVID-19, this isn’t the first pandemic to hit the world, even in recent times. In fact, there are many similarities between the COVID-19 pandemic, and its management, and others throughout history, UNSW historians say.

Researchers from the UNSW Laureate Centre for History & Population are investigating the laws and regulations that have restricted people’s movement within Australia during epidemics and pandemics over the past 120 years in an ARC Special Initiative Project, Rethinking Medico-Legal Borders: from international to internal histories. UNSW Arts, Design & Architecture Professor Alison Bashford, ARC Laureate and Director of the Centre undertaking the project, and UNSW Law & Justice Scientia Professor Jane McAdam, Director of the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, are leading the initiative.

Anti-lockdown protests and sporadic breaches of COVID-19 restrictions have been widely covered by media – and the researchers say history tells us people have flouted public health rules in previous pandemics, too.

“Mask non-compliance was certainly a feature of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, but one important difference between this behaviour in 1919 and during the COVID-19 pandemic is the way that information is disseminated,” says PhD student Tiarne Barratt.

“In 1919, public health information was spread via daily newspapers and word of mouth, unlike today, where we are experiencing an overload of information and misinformation via social and online media that is enabling anti-mask messaging to reach a significantly larger platform.”

Dr Chi Chi Huang, Postdoctoral Fellow, says that the post-war context of World War I also contributed to messaging and compliance in 1919, as governments used the rhetoric of a collective effort to great success.

“Troops were still returning home, and civilians were emerging out of a war mentality where there was already a heightened sense of ‘doing your part’.”

Read more: OPINION We’ve become used to wearing masks during COVID. But does that mean the habit will stick?

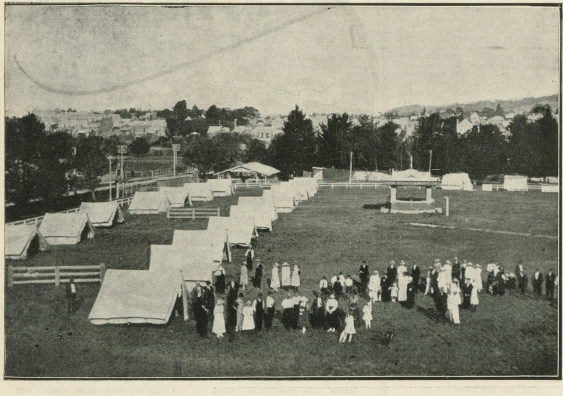

Attempts to regulate movement like social distancing, isolation, lockdowns today are also comparable to measures in the past. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic is perhaps the easiest comparison to COVID-19 internal border control in Australian history.

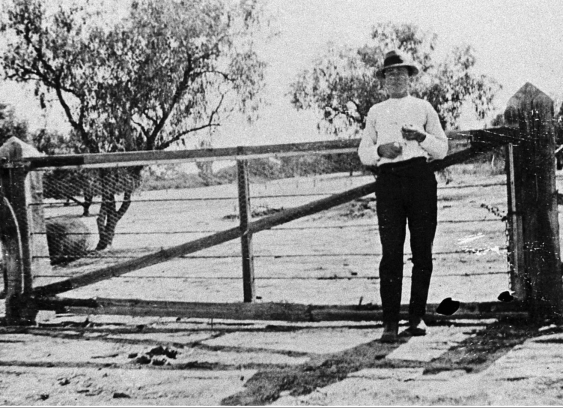

“[We] saw the closure of state borders and the regulation of intra-state borders to protect regional communities from city outbreaks. Beyond this, there were highly localised measures designed to regulate movement at a district level, such as the refusal of hoteliers to provide accommodation to travellers,” Ms Barratt says.

Policeman E.P. Ridge standing by the gate at the border of New South Wales and South Australia, Lake Littra, Chowilla, SA. 1919. Photo: State Library of South Australia, B 61162.

“However, all attempts to regulate internal movement ceased by August 1919, where in contrast, we are now more than 18 months into the COVID-19 pandemic episode and still seeing highly regulated inter and intra state movement.”

When it comes to current international border controls, Professor McAdam says: “There is now a strong argument that travel caps are arbitrarily depriving Australians’ of the right to return home, especially since contact tracing has improved, vaccinations have become widespread, community transmission of COVID-19 (not breaches of hotel quarantine) is the primary source of infection, and people who are infected in the community are allowed to self-isolate at home.”

Read more: OPINION The government just made it even harder for Australians to come home. Is this legal?

The researchers say when it comes to public health messaging, there are previous successful examples we could look to draw upon.

“Public health messaging was phenomenally successful in the Australian response to HIV/AIDS. The risk-reduction philosophy that drove the Australian response was highly successful, and globally heralded,” Professor Bashford says. “Especially with regard to the vaccination program, currently underway, this moment in Australian public health messaging might be remembered and utilised.”

However, the source of the public health messaging and the extent to which people trust or distrust that source is something that has been important both historically and today. For example, there generally is a correlation between general trust in government and levels of public health compliance, Ms Barratt says.

While we tend to date pandemics by the year they first emerged, each pandemic lasted decades, and their impacts lasted even longer, says Dr Huang.

“The occurrence of pandemics is an inevitability and dealing with the immediate crisis of a pandemic is, of course, important. But it is a long-term experience as we learn to continually respond to pandemics where public health is at the crux of ensuring a stable globalised society and economy.”

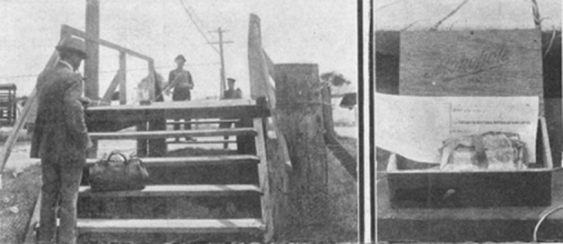

Banking Method at Tweed Heads, 1919. The method used by the manager of the E.S. and A. Bank at Tweed Heads do business with customers at Coolangatta. The depositor puts his cheques, notes, etc. in the cigar box (image on the right), which is drawn across the bridge over the border by means of a string. The manager receives the money, and returns the deposit slip or bank note the same way. Photo: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, 203579.

In terms of social resilience, there was a strong culture of volunteerism in Australia throughout the 1919 influenza pandemic. Indeed, Australia is remembered for demonstrating particularly positive attitudes and high levels of localised community support during the influenza pandemic, says Ms Barratt.

“For example, during home isolation, people were entirely reliant on their local community for survival, as no member of an afflicted household was allowed to leave the house. That meant many households around the country were dependent on their neighbours for food and other essentials such as firewood.”

Read more: Power to the sheeple: why common sense prevails despite COVID-19 uncertainty

Recent commentary has speculated about a post-Covid boom like the roaring twenties following the 1918-19 Flu Pandemic. However, the post-pandemic boom was compounded by the end of World War I, which saw a re-envisioning of the international spirit.

“The boom of the roaring twenties was also not evenly distributed within nations and across nations, where working class people did not share in the prosperity of that decade as memorialised in popular culture,” says Dr Huang.

“Perhaps this is something that history can tell us about any potential post-pandemic boom – that it will be uneven.”

Pandemic episodes of the past have also highlighted existing pressure points and social inequalities, revealing failing social infrastructures more starkly, Ms Barratt says.

“In the same way that experiences of the pandemic will be vastly different, for example between those who have been able to pivot to work-from-home setups, and those who have been faced with long periods of involuntary unemployment, so will any experiences of a post-pandemic boom.”

Read more: Is Australia's coronavirus bill a debt burden future generations must bear?