A type of bacteria not routinely tested for has been discovered as the second most common cause of bacterial gastroenteritis, in a study of over 300,000 patient samples.

A group of scientists at UNSW Sydney have discovered that a type of bacteria known as Aeromonas are the second most prevalent bacterial pathogen found in patients with gastroenteritis.

Gastroenteritis – commonly known as gastro – is a contagious short-term illness triggered by the infection and inflammation of the digestive system that causes vomiting and diarrhoea.

In a recent study led by Associate Professor Li Zhang, from the School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, surprising results have provided new information on the types of enteric bacteria – bacteria in the intestine – that can cause the stomach bug.

Until now, it has been believed that after Campylobacter, the most common cause of bacterial gastro is Salmonella infection.

“Our results have found that Aeromonas are the second most prevalent enteric bacterial pathogens across all age groups, and are in fact the most common enteric bacterial pathogens in children under 18 months,” says A/Prof. Zhang.

The latest findings, published today in Microbiology Spectrum, could have an impact on the diagnostic process for gastroenteritis and ultimately lead to more targeted treatment.

“With further research, once we’re able to figure out the source of infection, we may eventually be equipped with the knowledge of how best to prevent Aeromonas infection.”

A distinct infection pattern

“Historically, Aeromonas species have been largely overlooked and understudied, but they are increasingly recognised as emerging enteric pathogens globally,” says A/Prof. Zhang.

The team, which included PhD student Christopher Yuwono, analysed data from 341,330 patients with gastroenteritis in Australia between 2015 and 2019.

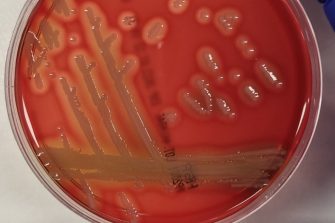

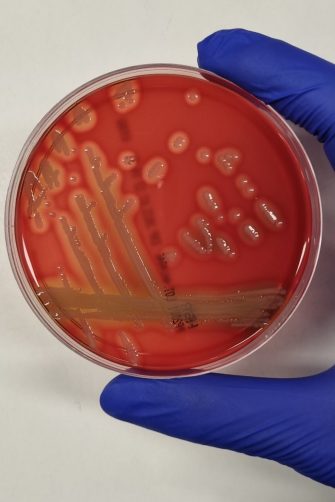

Using a method known as quantitative real-time PCR, faecal samples from these patients were tested to detect the presence of bacterial pathogens.

To get further insights into the factors influencing gastroenteritis infection, patient samples were grouped based on age groups.

On their analysis, the research team identified a unique infection pattern, characterised by three distinct infection peaks associated with patient age.

“The occurrence of Aeromonas enteric infections was predominately observed in young children and individuals over 50 years old, suggesting a higher susceptibility to these infections during stages where the immune system tends to be weaker,” says A/Prof. Zhang.

Additionally, there was an increase in Aeromonas enteric infections among patients aged 20-29 years, which could possibly be attributed to increased exposure to the pathogen at this age.

“These findings suggest that both human host and microbial factors contribute to the development of Aeromonas enteric infections.”

A change to diagnostic processes

Currently, when stool samples from gastro patients are sent to diagnostic laboratories Aeromonas enteric pathogens are not routinely detected.

“But the high rate of Aeromonas infection discovered in our study, and significantly, how they are impacting different patient age groups, suggest that Aeromonas species should be included on the common enteric bacterial pathogen examination list,” says A/Prof. Zhang.

The next step for A/Prof. Zhang and her team is to identify Aeromonas pathogens at a more detailed level. “We already know of at least five different species of Aeromonas cause gastrointestinal infections in Australia,” says A/Prof Zhang. “And we know that they have different virulent genes – with that some are more virulent than others. So if Aeromonas bacteria are identified to species level, it could lead to even more targeted treatment.”

The second challenge that faces A/Prof. Zhang is to identify the source of the pathogen. Previous research from the Zhang team demonstrated that the majority of Aeromonas enteric infections in Australia were locally acquired, with no history of overseas travel.

“Future research is needed to identify the sources of Aeromonas infections in Australia, so that effective strategies can then be implemented to reduce these infections.”