Brain scans and the science of crime

Can you identify a criminal by looking at their brain? Should head scans be admissible in a defence case? Can, and should, neuroscience help predict criminal behaviour?

Can you identify a criminal by looking at their brain? Should head scans be admissible in a defence case? Can, and should, neuroscience help predict criminal behaviour?

Can you tell who's a criminal by looking at their brain? Should head scans be admissible in a defence case? Can, and should, neuroscience help predict criminal behaviour?

These are some of the questions UNSW Law student Armin Alimardani explores in a PhD examining the intersection of neuroscience and the law.

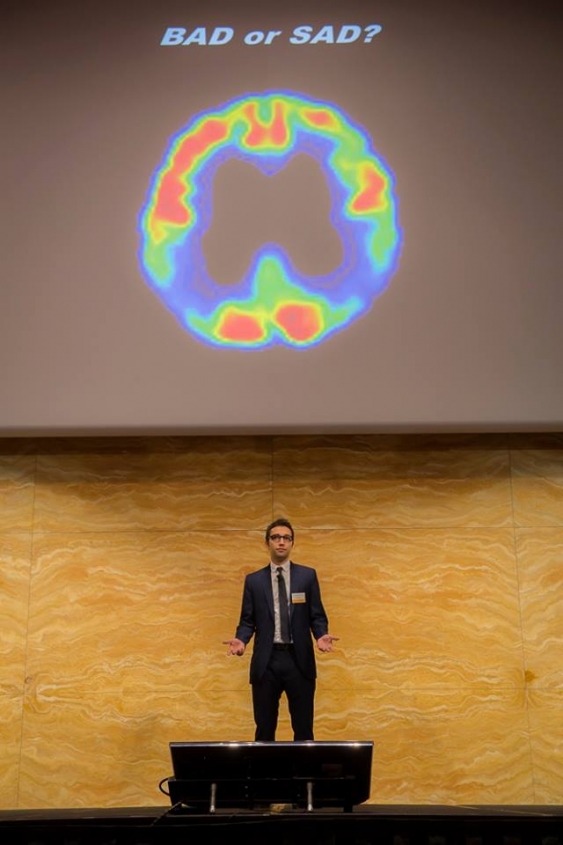

Alimardani won the 2015 Monash Criminology Postgraduate Prize for the most outstanding research presentation at the Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology’s postgraduate conference in November.

His talk looked at applying “fuzzy logic” – a non-binary way of coding information in computer engineering – to grade the severity of mental disorders among people accused of a crime.

“In cases where the accused has a mental disorder, experts use vague concepts like ‘poor’, ‘severe’ and ‘mild’, which can have different meanings for different judges and juries, and result in different sentences in similar cases,” says Alimardani, who was also a finalist in the 2015 UNSW Three Minute Thesis competition.

Can, and should, neuroscience help predict criminal behaviour? Armin Alimardani on stage at the 2015 UNSW Three Minute Thesis competition

“To address this problem, I proposed using ‘fuzzy logic’ – a common approach in electrical engineering – to more accurately determine the degree of a mental disorder.”

Instead of categorising information as a binary of either 0 or 1, fuzzy logic expresses data in increments between 0 and 1. For example, instead of seeing a glass as full (1) or empty (0), fuzzy logic can express the glass as being 0.3 full or 0.7 empty.

Using such a scale adds areas of grey to an otherwise black or white assessment

Alimardani’s PhD marries two of his great passions. The Iran-born and educated student had such an affinity with maths and engineering that he studied Information Technology alongside his law degree and was undecided about his path until discovering the field of criminology and the work of Cesare Lombroso.

Lombroso was a 19th century Italian physician who drove a paradigm shift in criminology towards the scientific study of criminals, positing that criminality was inherited and physically detectable.

Though now largely controversial, Alimardani believes that Lombroso’s work is relevant to both current genetic and neuroscientific studies of crime.

As scientific and technological advances creep into the courtroom, Alimardani is exploring what role neuroscientific evidence such as brain scans ought to have in criminal proceedings and how this can be reflected in the law.

It’s been 30 years since the first brain scan was submitted in a criminal trial, when John Hinckley used a CT scan to prove a defence of insanity in his attempted assassination of US President Ronald Reagan, but “we still don’t know how we should use this evidence”, says Alimardani.

Some areas of the brain, notably the frontal lobe, have been linked to disorders in impulse control and brain scans could be used to support a claim of diminished responsibility, resulting in a lesser sentence.

Alimardani says brain imaging could also be used to help identify criminals at risk of reoffending and target them for additional support, improving justice and outcomes for society.

Though not yet widely accepted in Australia’s legal system, he says the related field of behavioural genetics is already having an impact in courts overseas

For example, reduced sentences have been handed down in the US and Italy to offenders with variations in the monoamine oxidase-A gene. Low MAO-A expression has been linked to aggressive and violent behaviour.

Despite their growing place in the justice system, neuroscience and biology are just one dimension of criminal behaviour, with environmental and psychological factors deservedly prominent, Alimardani says.

“I believe we are missing so many useful approaches from other fields which can help us to improve justice, and finding these connections excites me.

“In many cases studying law without considering other disciplines is just trial and error. We can’t sit at our desk and wonder what makes a crime happen: we need other disciplines to really understand the problem.”