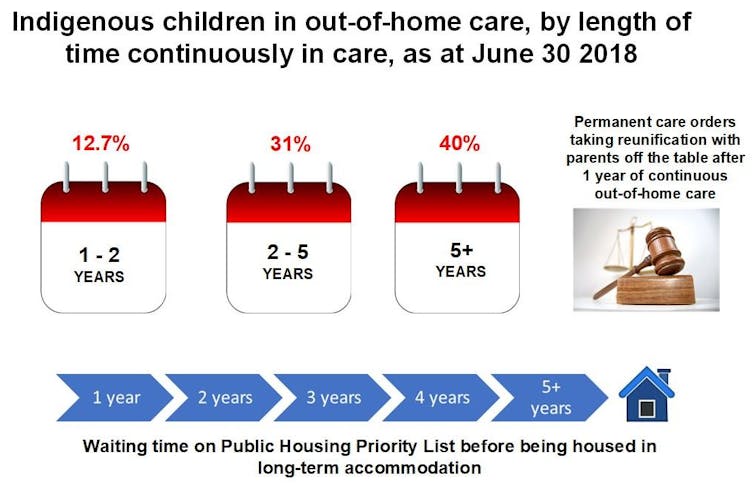

Another stolen generation looms unless Indigenous women fleeing violence can find safe housing

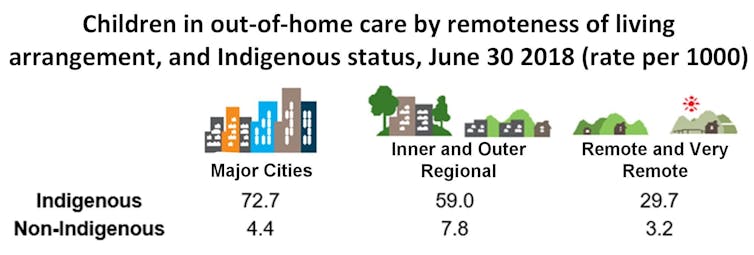

Indigenous children are admitted to out-of-home care at 11 times the rate for non-Indigenous children. The lack of safe housing for mothers fleeing family violence is a key factor.