Engineers from UNSW Sydney are using their best-practice approach to restore our wetlands.

When soil goes acid, the downstream effects on ecosystems and waterways can be devastating – but UNSW Sydney engineers have developed best-practice methods to turn our wetlands into areas where aquatic life and bird populations can thrive again.

Over the past 20 years, the Water Research Laboratory (WRL) at UNSW has undertaken on-ground projects to rehabilitate, repair and restore large wetlands across Australia.

Their approach, widely accepted as best practice, is to return disturbed environments back to the most natural state with the greatest environmental value, requiring as little human maintenance as possible.

The team does this by understanding the constraints of the site, such as tidal rage, rainfall, topography and adjacent landholders as well as learning from nature to ensure that local species will naturally repopulate at the site once the hydrology has been restored.

A key factor to the Laboratory’s success is their engagement with partners, such as landholders, councils and adjoining farmers, to ensure that all issues are taken in account before designing their restoration strategy.

The Big Swamp

One site that has been given new life is the Big Swamp, a series of drained agricultural floodplains on the Manning River estuary on the mid-north coast of NSW.

The seven-year collaborative project saw the WRL partner with Greater Taree City Council and WetlandCare Australia to restore the area which was once known as one of the worst Acid Sulfate Soil hotspots in NSW. The soil near the surface there has a pH of three, which can turn the surface waters that flow onto downstream waterways extremely acid, often leading to a loss of aquatic life.

Associate Professor Will Glamore, team leader on the project and chief investigator of eco-engineering at the WRL, says that working so closely with partners was the key to their success.

“The Big Swamp Restoration Project is a great example of what can be achieved with large-scale restoration,” said Glamore.

“Working with our partners at Council, we were able to turn a polluted site into a valuable asset for future generations. Having partners like the Council and National Parks, who are willing to take a risk on research, has helped us to develop a method that is now being applied countrywide.

“In the end it’s about getting the right amount of water in the right places for the right amount of time. If you get this right, nature responds, and everyone is a winner.”

Principal engineer in the WRL, Duncan Rayner, says that they’ve already seen a major improvement in the water quality, which has reduced impacts to the downstream estuary.

“We established freshwater and intertidal wetlands, and now fish, prawn and bird populations have increased – with inter-tidal mangrove and saltmarsh wetlands acting as the fish nurseries of the estuary and creating primary habitat that supports both recreation and commercial fishery in the area,” says Rayner.

WRL engineer and Manning Valley local, Jamie Ruprecht, says that the benefits of restoring the wetland areas are evident in the local area. “These improvements have resulted in benefits across the Manning River valley, as previously lost wetland habitats are restored and connectivity between key fish and bird habitats improved,” said Ruprecht.

Implementing their best practice approach

To achieve this, the team first analysed the constraints of the site such as tidal range, rainfall, topography and adjacent landholders. They also looked at the natural habitat to ensure that the local species would naturally re-populate the site once it had been restored.

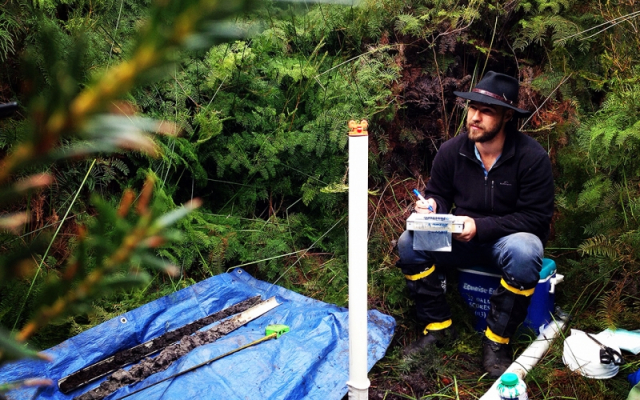

As part of the design process, they collected data over a 12-month period which included on-site monitoring of surface and groundwater quality, and testing soil characteristics by digging soil profiles by hand.

Their results showed that the water acidity has improved from a pH3 to pH6, allowing natural vegetation to repopulate and setting the foundations for local fish and bird life. They were also able to re-establish oyster farming for the first time since the 1970s.

The team now provide support to the maintenance of the area: since implementing the restoration strategy, the WRL still work with Council to monitor the water quality improvement and the ecological response.

They are now working with the Council to expand the restoration areas of other sites that still have low environmental value and impact the downstream Manning River estuary.

A leader in water engineering

The Water Research Laboratory (WRL) is a world-leading fundamental and applied research organisation, tackling the most challenging water engineering problems faced by the world today. Based on Sydney’s Northern Beaches and part of the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UNSW, the globally-esteemed laboratory spans four hectares and is home to state-of-the-art facilities, equipment and personnel comprising the most experienced and creative engineers and researchers in their respective areas of research and industry.