You probably wouldn’t be surprised to hear that people who use heroin, methamphetamine or crack cocaine are heavy users of emergency departments. The daily challenges of using these drugs mean that appointment-only services are difficult to navigate, and health is not always the top priority. Hospital-based studies appear to support this view, showing that frequent patients often use drugs and alcohol. But these perceptions might just reflect the patients who happen to turn up in hospital rather than the whole population.

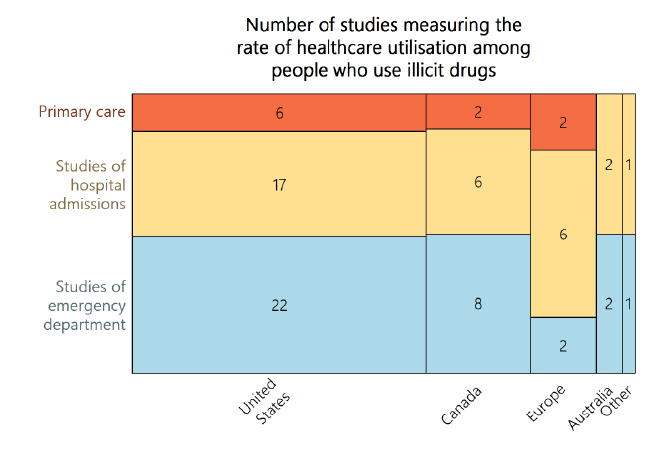

To get a better understanding of healthcare for this group, we conducted a systematic review of 92 studies that recruited people who use illicit drugs from the community and then followed them up to see how often they used health services.

The rate of emergency department use was high for people who use illicit drugs, on average five times the general population. The rate of hospital admission was typically seven times the general population. In part, this reflects the poor health outcomes and well-documented high mortality rates associated with long-term drug use. But the results also told us a lot more.

The rate of emergency department use was high for people who use illicit drugs, on average five times the general population. The rate of hospital admission was typically seven times the general population. In part, this reflects the poor health outcomes and well-documented high mortality rates associated with long-term drug use. But the results also told us a lot more.

- We need to understand how GPs work with patients who use drugs. Primary care is the front line of the health service and accounts for about a third of health spending. But there is minimal research into how often and why people who use drugs visit GPs. While there is a perception that GPs are not well-designed for marginalised groups, the few studies that included data from primary care found that patients who use drugs visit often. The lack of research in this area means that it is difficult to determine whether the high rate of hospital use is related to poor primary care, or whether it is simply because people who use drugs have poorer health.

- Local health systems can be very different in terms of accessibility. Health systems vary around the world, so you would expect variation in rates of healthcare use. In Germany, for example, people are admitted to hospital three times more often than people in neighbouring Netherlands. But the variation between studies of people who use drugs is much bigger than that, even for similar populations in the same country. For example, within the United States, the rate of hospital admission for people in treatment for opiate dependence ranged ten-fold, from 51 to 592 per 100 person-years. This suggests that local health systems vary widely in terms of their accessibility for people who use drugs.

- People who use drugs access healthcare for a wide range of infections and non-communicable diseases. It’s not just overdose, withdrawal and opiate substitution scripts. In fact, these issues accounted only 10-20 per cent of hospital episodes in studies in the review. We recently looked at the causes of hospital admission for 6683 people who use heroin in London, and found that only one in seven were 'drug related'. Just like the general population, people who use drugs visit hospital for a very wide range of reasons, with respiratory diseases, liver disease, skin infections and mental health problems all very common.

Most research to date has focused on overdoses and blood-borne viruses, and there are now effective methods of preventing and treating these problems (though these interventions are not always easy to access). However, most excess morbidity and mortality in this group relates to common long-term conditions, which are often undiagnosed and untreated.

Healthcare systems are not always easy to navigate for people who use drugs, and this review shows the resulting high use of hospital services. We need to understand the role of primary care and find models that are accessible, so people don’t end up in hospital.

Citation

Lewer D, Freer J, King E, Larney S, Degenhardt L, Tweed EJ, Hope VD, Harris M, Millar T, Hayward A, Ciccarone D, Morley KI. Frequency of healthcare utilisation by adults who use illicit drugs: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction 2019. DOI:10.1111/add.14892.

About the author

Dan Lewer is a public health registrar in London and an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow at UCL. His research focuses on how the NHS in the UK can provide better care for physical health problems among people who use heroin and crack cocaine. He is a visiting research fellow at the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, where he is researching healthcare quality for people prescribed opiate substitution therapy in Australia.