Next-generation solar cells pass strict international tests

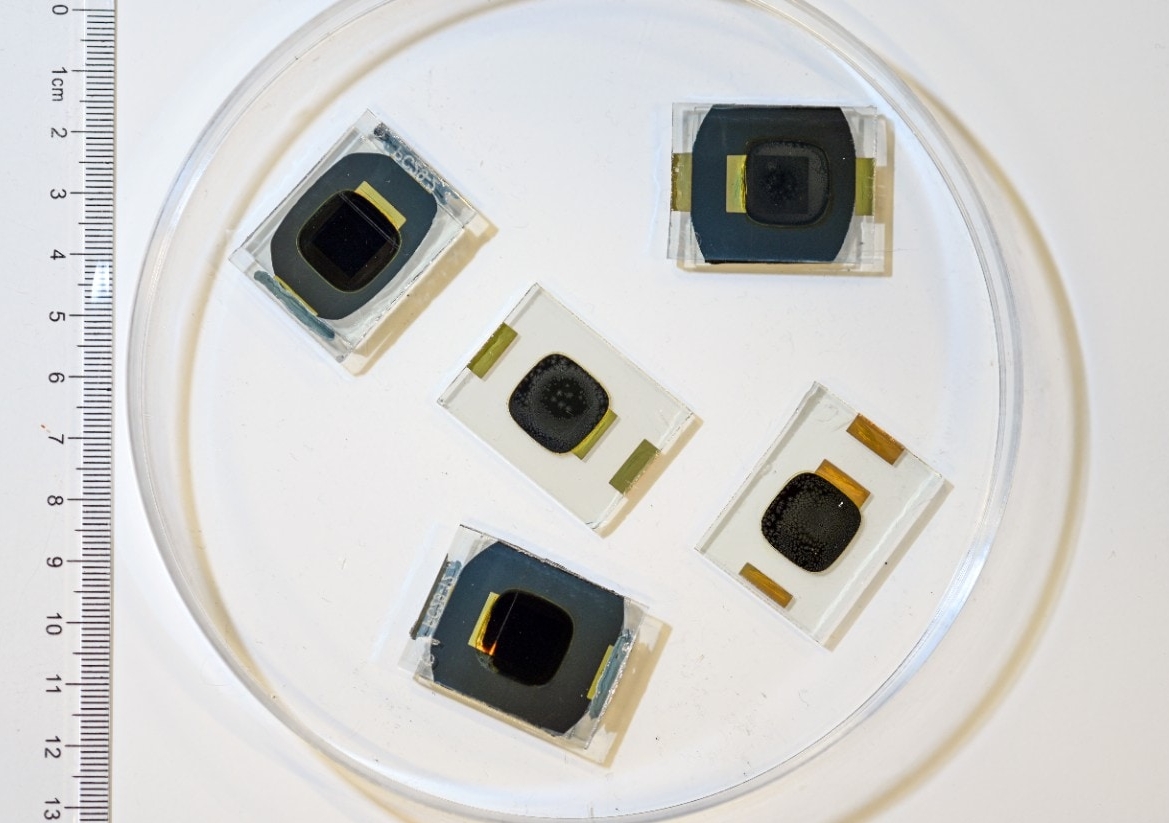

Light-weight, cheap and ultra-thin perovskite crystals have promised to shake-up renewable energy for some time. Research led by Professor Anita Ho-Baillie means they are ready to take the next steps towards commercialisation.