Targeting stem cells: towards improved treatment for poor-prognosis leukaemia

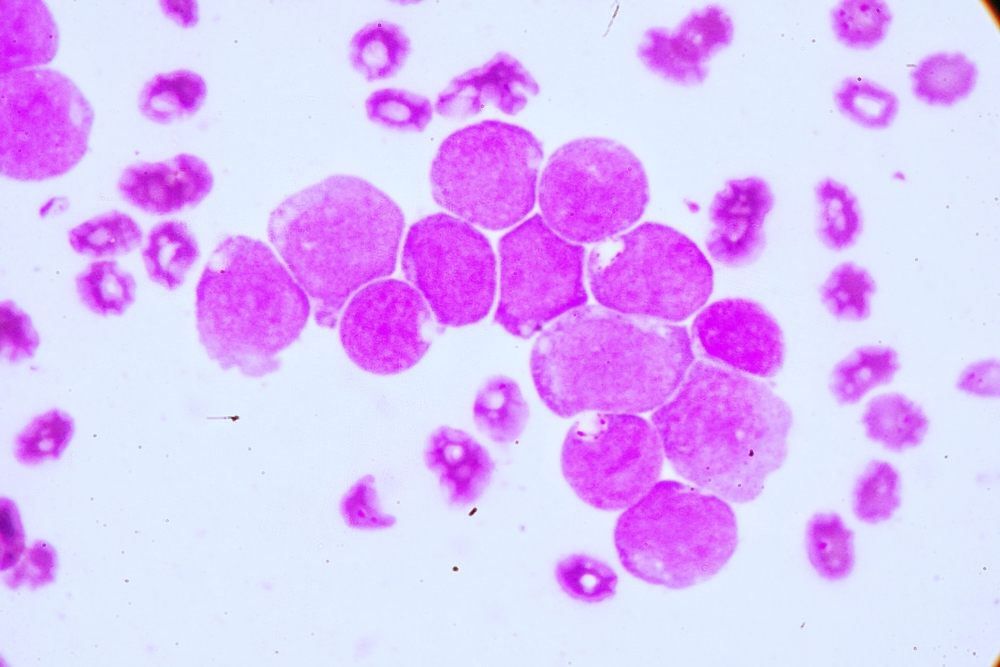

Researchers at Children’s Cancer Institute and UNSW have discovered in mice what could one day develop into a new and improved way to treat the poor-prognosis blood cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia or AML.