Scientists test potential drug developed in Australia to treat common causes of blindness: pre-clinical study

A new chemical compound could become a future tool against retinal vascular disease, a pre-clinical study has shown.

A new chemical compound could become a future tool against retinal vascular disease, a pre-clinical study has shown.

An international team led by UNSW medical researchers has tested a chemical compound in the lab and a range of animal models to progress much-needed treatment options for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy (DR), the main eye complication of diabetes.

While the preclinical studies provide hope to patients with AMD and DR, further work is needed to see if this compound is well tolerated and efficacious in humans.

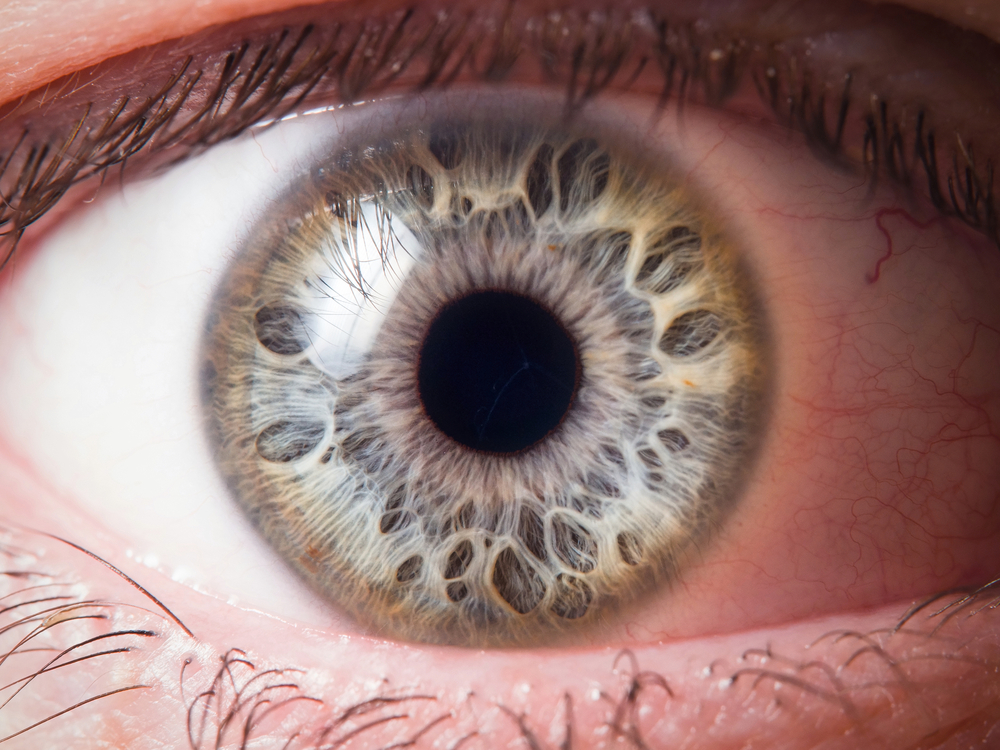

AMD and DR are leading causes of visual loss and blindness in Australia. These diseases involve abnormal leaky blood vessels in the retina.

“All current approved targeted therapies for AMD and DR are antibodies and protein-based drugs that suppress a specific growth factor system called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),” says lead author Professor Levon Khachigian from UNSW Medicine.

“But many patients do not respond optimally to those treatments, or at all, and small molecule therapies aren’t available – that’s why we need alternative approaches to those that only target the VEGF system.”

To help work towards those alternative approaches, Prof. Khachigian and his team have identified a small molecule chemical compound called BT2 that shuts down a key cell signaling pathway that serves as an “on switch” for many diseases.

“Small molecules are potentially cheaper to produce than antibodies and protein-based drugs, and may reduce costs to health systems for AMD and DR,” said Prof. Khachigian.

To explore the potential therapeutic effects of BT2, the team performed studies in mice, rats and rabbits.

“In rodents, we found that BT2 reduced fluid leakage from abnormal blood vessels in the retina at least as effectively as the current first-line targeted therapy for AMD and DR,” Prof. Khachigian says.

“We also found that BT2 is remarkably thermostable. It retains biological activity after boiling or autoclaving and several months’ sitting in a drawer at room temperature. This contrasts with antibodies and other proteins that are typically inactivated by heat.”

The team says they found that BT2 also inhibited a large range of other regulatory genes involved in processes that drive the pathogenesis of retinal vascular as well as other diseases that involve inflammation.

“Our “transcriptomics” analysis shows that BT2 suppressed not only VEGF, but inhibited around 1 in 4 genes activated by a classic mediator of vascular leakiness, angiogenesis and inflammation called interleukin-1beta,” Prof. Khachigian says.

“This suggests that BT2 may potentially offer broader protection than existing drugs that focus solely on the VEGF system,” says Professor Paul Mitchell, internationally renowned ophthalmologist and one of the study authors.

“BT2 could potentially add to doctors’ toolbox of therapeutic options down the track,” says Prof. Mitchell.

“BT2 may serve as a potential new small molecule drug for AMD or DR by inhibiting key pathologic changes beyond those just caused by the VEGF system,” Prof. Khachigian said. “BT2 could potentially be useful to patients who respond poorly to current drugs just targeting the VEGF system.”

“This is early research – the path toward clinical translation will require a lot more work.”

1 in 7 Australians over 50 years old – 1.3 million people – have some signs of macular degeneration. 50 per cent of Australians over age 55 who are blind, are blind because of AMD.

1.7 million Australians have diabetes. 300,000 (between 25-35 per cent of people with diabetes) have some degree of DR and 65,000 have sight-threatening eye disease.

BT2 was wholly developed in Australia with additional preclinical testing performed in Europe.

This study was funded by NHMRC and Cancer Institute NSW.