Robo-pets: a new breed of fur baby

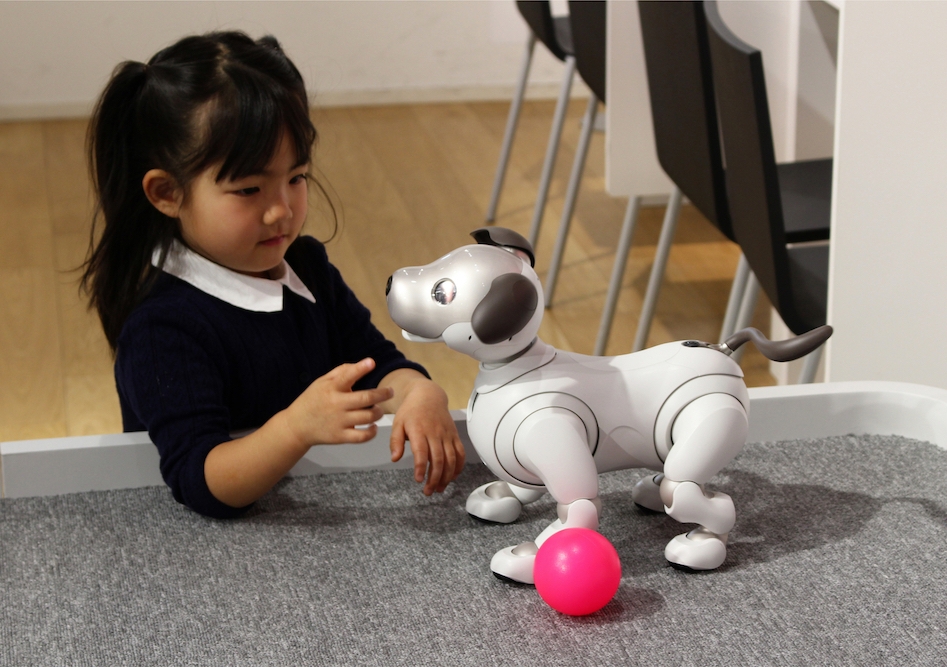

If having a pet just isn’t practical for your lifestyle, could a robotic companion be the next best thing?

If having a pet just isn’t practical for your lifestyle, could a robotic companion be the next best thing?

For many reasons, a pet might not be suitable for your living situation. But that doesn’t mean you need to miss out on the love and affection of a four-legged friend.

Whether you’re an animal lover with a dog-sized heart, or you just want a little more companionship, a robot pet might be for you. Modelled after the image of their real-life counterparts, these interactive companion robots could help fill the void of humankind’s best friend and much more – batteries not included.

Social robotics researchers from UNSW are optimistic about their benefits and believe they could very well enter our homes, and our hearts, very soon.

“Robotic pets can be low maintenance, sterile, hypoallergenic and cannot catch or pass on disease. They work for those who would like a companion, but cannot be in contact with a live animal, or cannot care for one,” says Belinda Dunstan, human-machine interaction lecturer at UNSW School of Built Environment.

Dr Dunstan, who researches social robotics, says while it might sound unusual, it’s actually normal for people to care for a range of objects, including robots. In fact, it has been found that up to 80% of Roomba vacuum cleaner owners name their vacuum.

“It’s quite natural for us to form attachments to embodied objects, and particularly ones that exhibit some sense of sentience,” she says.

“We have a spectrum of care-based relationships and connections: friends, lovers, pets, colleagues, neighbours, houseplants – people even name their sourdough yeast starters. I see robotic pets as fitting into that spectrum and just being another avenue for humans to exhibit care and connection.”

One of the most effective uses of robotic companion pets so far has been in assisted living environments. In scenarios where it’s unsuitable to have real pets, robotic pets can be highly effective companions, such as PARO, an interactive robotic seal, used for animal therapy with dementia patients.

“PARO is successful because there’s a very clear use case for dementia patients who can’t have a real animal in that space,” says Scott Brown, Assistive Technology Lead at the Creative Robotics Lab, UNSW Art & Design says. “It plays well into the limited complexity of robots compared with an animal, so somebody with dementia can cope with it.”

Robotic pets could also be beneficial for those with anxiety around animals. Dr Brown says a robotic companion animal could be used to help overcome fears about interacting with a real dog.

“Interacting with a robot dog first could translate to people being more comfortable around real dogs. It wouldn’t be too dissimilar to what we’re doing with Kaspar, using it as a surrogate for the real-world experience for children with autism…it doesn’t replace interaction, but it would be a stepping stone.”

He says we could be ready to see more robotic companion pets in our homes, too. We’re becoming more receptive to relationships with robots, beginning in childhood.

“[Many of] the toys we see today are on a spectrum of robotics,” he says. “It’s something that is becoming very common, and we’re becoming a lot more comfortable with the idea.”

He says our relationship to a robotic family pet might not be too different from a Tamagotchi (we might even forget to feed it from time to time).

“You have this care responsibility with the Tamagotchi that is key in building that relationship...that is something that is potentially [amplified] with an embodied object like a robotic companion animal,” he says.

However, Dr Brown says we shouldn’t expect robotic pets to replace the real thing anytime soon. In addition to being quite expensive, consumer robotics lack the ability to replicate an animal comprehensively.

“The perception of what a robot can actually do, at this point, is far beyond what robots are able to do,” he says. “I wouldn’t expect in the next five years that we will see the robots that can replicate enough of an animal that it will be a case of one or the other.”

Dr Dunstan also agrees that we won’t see our relationships with robotic pets replace human-pet interactions.

“The direction social robotics is going is collaborative, assistive and augmenting human activity so they exist alongside and help us with things. We do not see a trend towards any relationship replacement, and I think the same could be said for robotic pets.”

She says the most effective use of social robots like robotic pets is not in replacing interaction with animals, but augmenting or sitting alongside our other kinds of relationships.

“Rather than thinking of robotic pets as a poor replacement for a dog, we should broaden our ideas about the types of human relationships that we have, all of which are beneficial, and none of which substitute the other,” she says.

While robotic pets might not necessarily replace pets, they are ultimately another opportunity for caring relationships which, Dr Dunstan says, is always a good thing.

“I’m really optimistic about any form of connection, expressions-of-care opportunities for relationships and varied kinds of caring relationships. I think those are always positive for humans,” Dr Dunstan says.

“Particularly if social isolation is something that continues, or is more common in the future, I think any opportunity for caregiving is very valuable. We’ve seen this year in particular just how essential it really is.”