Life, the universe and everything: some of our most-read science stories of 2020

The most-read stories of 2020 take us from the depths of the mind to the edges of the universe.

The most-read stories of 2020 take us from the depths of the mind to the edges of the universe.

2020 might have been the year that we stayed home, but it hasn’t stopped researchers at UNSW Sydney from communicating their important scientific research to the public.

From addressing the challenges of today (like learning how to parent during a pandemic), to identifying the challenges of tomorrow (like the risks facing platypuses and sea levels), UNSW academics and researchers have been helping readers build their knowledge of the world around us.

To celebrate the end of the year, we look back at some of the science stories that captured our readers’ attention.

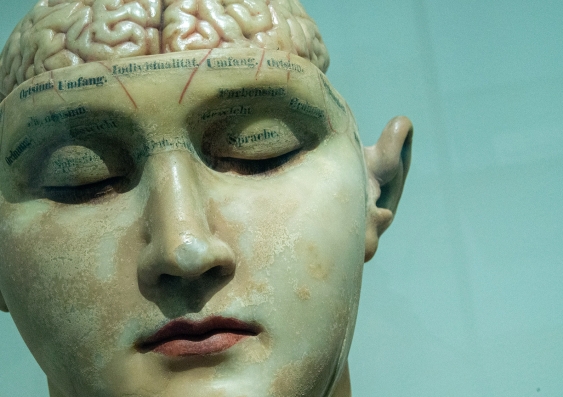

Aphantasia – being blind in the mind’s eye – may be linked to more cognitive functions than previously thought, new research from UNSW Sydney shows.

Up to one million Australians could have aphantasia, but we know very little about the condition. Photo: Unsplash.

Picture the sun setting over the ocean. It’s large above the horizon, spreading an orange-pink glow across the sky. Seagulls are flying overhead and your toes are in the sand.

Many people will have been able to picture the sunset clearly and vividly – almost like seeing the real thing. For others, the image would have been vague and fleeting, but still there.

If your mind was completely blank and you couldn’t visualise anything at all, then you might be one of the 2-5 per cent of people who have aphantasia, a condition that involves a lack of all mental visual imagery.

A new study led by researchers at UNSW Science surveyed over 250 people who self-identified as having aphantasia. It found that aphantasia isn’t just associated with the absence of visual imagery – but also with a widespread pattern of changes to other important cognitive processes.

Dr Georgie Fleming recommends five “pandemic parenting” strategies – including how to best use special play, praise, rewards, consequences and self-care.

Increased parenting time and responsibilities and less self-care almost guarantees that parents will experience more stress and anxiety - but there are ways to work against this. Photo: Shutterstock

I am a researcher and clinical psychologist specialising in childhood disruptive behaviour problems and when I first heard that schools in some parts of the country were closing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, my first thought was “oh man, what about the parents?”.

As part of my clinical research, I’ve spent the last six years in weekly sessions with families, helping parents develop strategies to more effectively manage their kid’s defiance and aggression. Parenting is hard. But parenting in a pandemic? Well, that’s next level.

There is good news, though. There are practical strategies that parents can use to stop their household descending into a Lord of the Flies-esque scenario where the kids are in charge and it’s your head on the stick.

Not only does a universal constant seem annoyingly inconstant at the outer fringes of the cosmos, it occurs in only one direction, which is downright weird.

Scientists examining the light from one of the furthermost quasars in the universe were astonished to find fluctuations in the electromagnetic force. Picture: Shutterstock

Those looking forward to a day when science’s Grand Unifying Theory of Everything could be worn on a t-shirt may have to wait a little longer as astrophysicists continue to find hints that one of the cosmological constants is not so constant after all.

In a paper published in Science Advances, scientists from UNSW Sydney reported that four new measurements of light emitted from a quasar 13 billion light years away reaffirm past studies that found tiny variations in the fine structure constant.

UNSW Science’s Professor John Webb says the fine structure constant is a measure of electromagnetism – one of the four fundamental forces in nature (the others are gravity, weak nuclear force and strong nuclear force).

The electromagnetic force keeps electrons whizzing around a nucleus in every atom of the universe – without it, all matter would fly apart. Up until recently, it was believed to be an unchanging force throughout time and space. But over the last two decades, Professor Webb has noticed anomalies in the fine structure constant whereby electromagnetic force measured in one particular direction of the universe seems ever so slightly different.

Rising ocean temperatures drove the melting of Antarctic ice sheets and caused extreme sea level rise more than 100,000 years ago, a new international study led by UNSW Sydney shows.

Fine layers of ancient volcanic ash in the ice helped the team pinpoint when the mass melting took place. Photo: AntarcticScience.com

Mass melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was a major cause of high sea levels during a period known as the Last Interglacial (129,000-116,000 years ago), an international team of scientists led by UNSW’s Chris Turney has found. The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The extreme ice loss caused a multi-metre rise in global mean sea levels – and it took less than 2˚C of ocean warming for it to occur.

“Not only did we lose a lot of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, but this happened very early during the Last Interglacial,” says Chris Turney, Professor in Earth and Climate Science at UNSW Sydney and lead author of the study.

New UNSW research calls for national action to minimise the risk of the platypus vanishing due to habitat destruction, dams and weirs.

New UNSW research starts to monitor the iconic Australian platypus which faces multiple threats including climate change and human-related habitat loss. Picture: UNSW Science

Australia’s devastating drought is having a critical impact on the iconic platypus, a globally unique mammal, with increasing reports of rivers drying up and platypuses becoming stranded.

Platypuses were once considered widespread across the eastern Australian mainland and Tasmania, although not a lot is known about their distribution or abundance because of the species’ secretive and nocturnal nature.

A new study led by UNSW Sydney’s Centre for Ecosystem Science, funded through a UNSW-led Australian Research Council project and supported by the Taronga Conservation Society, has for the first time examined the risks of extinction for this intriguing animal.

Picture the sun setting over the ocean. It’s large above the horizon, spreading an orange-pink glow across the sky. Seagulls are flying overhead and your toes are in the sand.

Many people will have been able to picture the sunset clearly and vividly – almost like seeing the real thing. For others, the image would have been vague and fleeting, but still there.

If your mind was completely blank and you couldn’t visualise anything at all, then you might be one of the 2-5 per cent of people who have aphantasia, a condition that involves a lack of all mental visual imagery.

A new study led by researchers at UNSW Science surveyed over 250 people who self-identified as having aphantasia. It found that aphantasia isn’t just associated with the absence of visual imagery – but also with a widespread pattern of changes to other important cognitive processes.

Dr Georgie Fleming recommends five “pandemic parenting” strategies – including how to best use special play, praise, rewards, consequences and self-care.

I am a researcher and clinical psychologist specialising in childhood disruptive behaviour problems and when I first heard that schools in some parts of the country were closing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, my first thought was “oh man, what about the parents?”.

As part of my clinical research, I’ve spent the last six years in weekly sessions with families, helping parents develop strategies to more effectively manage their kid’s defiance and aggression. Parenting is hard. But parenting in a pandemic? Well, that’s next level.

There is good news, though. There are practical strategies that parents can use to stop their household descending into a Lord of the Flies-esque scenario where the kids are in charge and it’s your head on the stick.

Not only does a universal constant seem annoyingly inconstant at the outer fringes of the cosmos, it occurs in only one direction, which is downright weird.

Those looking forward to a day when science’s Grand Unifying Theory of Everything could be worn on a t-shirt may have to wait a little longer as astrophysicists continue to find hints that one of the cosmological constants is not so constant after all.

In a paper published in Science Advances, scientists from UNSW Sydney reported that four new measurements of light emitted from a quasar 13 billion light years away reaffirm past studies that found tiny variations in the fine structure constant.

UNSW Science’s Professor John Webb says the fine structure constant is a measure of electromagnetism – one of the four fundamental forces in nature (the others are gravity, weak nuclear force and strong nuclear force).

The electromagnetic force keeps electrons whizzing around a nucleus in every atom of the universe – without it, all matter would fly apart. Up until recently, it was believed to be an unchanging force throughout time and space. But over the last two decades, Professor Webb has noticed anomalies in the fine structure constant whereby electromagnetic force measured in one particular direction of the universe seems ever so slightly different.

Rising ocean temperatures drove the melting of Antarctic ice sheets and caused extreme sea level rise more than 100,000 years ago, a new international study led by UNSW Sydney shows.

Mass melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was a major cause of high sea levels during a period known as the Last Interglacial (129,000-116,000 years ago), an international team of scientists led by UNSW’s Chris Turney has found. The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The extreme ice loss caused a multi-metre rise in global mean sea levels – and it took less than 2˚C of ocean warming for it to occur.

“Not only did we lose a lot of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, but this happened very early during the Last Interglacial,” says Chris Turney, Professor in Earth and Climate Science at UNSW Sydney and lead author of the study.

New UNSW research calls for national action to minimise the risk of the platypus vanishing due to habitat destruction, dams and weirs.

Australia’s devastating drought is having a critical impact on the iconic platypus, a globally unique mammal, with increasing reports of rivers drying up and platypuses becoming stranded.

Platypuses were once considered widespread across the eastern Australian mainland and Tasmania, although not a lot is known about their distribution or abundance because of the species’ secretive and nocturnal nature.

A new study led by UNSW Sydney’s Centre for Ecosystem Science, funded through a UNSW-led Australian Research Council project and supported by the Taronga Conservation Society, has for the first time examined the risks of extinction for this intriguing animal.