Under the sea: weird and wonderful creatures to look for while snorkelling this summer

Overseas travel might be off the table this summer, but why not travel under it?

Overseas travel might be off the table this summer, but why not travel under it?

Australia’s oceans are filled with creatures that seem too magical to be true.

From the tasselled beard of a wobbegong shark, to the changing colour of a mourning cuttlefish, there are countless spectacular creatures that move and interact in ways not seen on land.

“Beyond fish, there are a vast array of wildly different animals and plants reflecting billions of years of evolution in our oceans,” says Professor Emma Johnston, marine ecologist and Dean of Science at UNSW Sydney.

“Diversity at the very highest levels is greater in the ocean than on land.”

Ahead of the summer holidays, we spoke to six UNSW Science researchers about their favourite creatures to look for while snorkelling. Not only do they share why these creatures are fascinating, but they also give tips for swimmers and snorkellers trying to find them.

Prof. Johnston says Australia’s marine ecosystems are treasure troves of biodiversity but if you want to see lots of big fish you should snorkel in a marine park sanctuary zone.

“In just 10 minutes underwater you can see animals from 10 different phyla – for example, sponges, flatworms, shellfish, sea squirts, roundworms, anemones, urchins, lace corals, tube worms, and comb jellies,” she says.

The creatures listed below are just a hint at the diverse lifeforms under the surface. While some of these species might take longer to find, with a bit of patience, you might be lucky enough to spot all of them.

Nudibranchs are famous for their vibrant, eye-catching colours. Photo: Niki Hubbard.

“Nudibranchs – the teeny-tiny slugs of the sea – are a real underwater treasure,” says marine and behavioural ecologist, Mr Niki Hubbard.

“They are usually tiny but make up for lack of size with their magnificent colours and patterns.”

Nudibranchs are a group of jelly-bodied molluscs known by their vibrant appearance. The colourful creatures are also hermaphrodites, with the ability to mate with any other member of their species.

There are over 3000 known nudibranch species worldwide and around 700 in Australia. Nudibranchs can be tricky to spot – but finding them is all part of the fun.

“It can be so rewarding to spot that tiny flash of colour making its slow and steady way across one of the rocky reefs around Sydney,” says Mr Hubbard, who is currently studying the impact of artificial light on coastal ecosystems for his PhD.

Why so blue? A Bennett's Hypselodoris nudibranch spotted in Gordon's Bay, Coogee. Photo: Niki Hubbard.

He suggests looking for nudibranchs in one of Sydney's many tidepools or while snorkelling in the shallows just off a rocky shore.

“Nudibranchs can be as small as a few millimetres in length, so you really need to look hard and explore their worlds up close,” says Mr Hubbard. “Try looking on rock faces just beneath the surface of the water.

“Many nudibranchs and sea slugs tend to have a favourite food, so a bit of prior research before your snorkel can help to narrow down your search.

“Finding their favourite sponge snack, for example, can definitely increase your chances of spotting nudibranchs hanging around.”

Crayweed 'teens' growing in Malabar, Sydney. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

When research assistant Ms Madelaine Langley emerges from the water after a snorkel, passersby often stop to ask her if she saw anything exciting.

They usually think she is joking when she responds: lots of seaweed!

“Most of us can appreciate the beauty of the tall eucalypts as we go bushwalking over the summer,” says Ms Langley. “We admire the way the light shines through the foliage, the way they sway in the wind, and the animals that call them home.

“I hope people can apply that same appreciation to our underwater forests this summer, which provide similarly crucial habitat.”

Ms Langley’s favourite type of underwater forest is formed by the golden-green Phyllospora comosa, commonly known as crayweed. The species became locally extinct in Sydney in the late 20th century, but Ms Langley is part of a team of scientists trying to change that.

Craybies in their early stages in life. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

“Operation Crayweed, run by UNSW and the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, is transplanting crayweed back to the reefs where they used to thrive,” she says. “We started by restoring small patches of crayweed from nearby healthy forests just outside Sydney and are now starting to see crayweed spreading hundreds of metres away.”

The first sign of this spread is the appearance of crayweed babies, or ‘craybies’. Craybies appear nestled below existing seaweed canopy a few months after re-planting.

“Craybies may look insignificant, but to me these tiny fronds represent resilience, growth and hope in a sea of uncertainty,” says Ms Langley, who suggests looking for craybies at Shelly Beach, Freshwater, North Bondi and Malabar.

“Swim along the rocky reef until you locate the restoration mats,” she says. “On these mats you will find crayweed ‘transplants’ attached with rubber materials. Work outwards from here, checking underneath nearby seaweed canopy for craybies.”

Operation Crayweed want to hear about any crayweed sightings this summer. To report a sighting, contact the team via their website or iNaturalist page.

It wasn't until Ms Rosie Steinberg checked her camera roll that she realised there were two, not one, octopuses keeping her company. Photo: Rosie Steinberg.

“Octopuses are especially fun because they are so hard to spot,” says marine scientist and coral researcher Ms Rosie Steinberg, who is currently researching the ecology of soft corals for her PhD.

The Sydney octopus, also called the ‘gloomy octopus’, is typically grey or brown with orange-rust red arms. These arms – which can span up to two metres – help the octopus crawl on rocks or to propel through water.

Octopuses can also be territorial, defending their lair during the day and feeding on prey at night.

While there aren’t any tricks to finding octopuses (“They go where they please!” says Ms Steinberg), there are some things you can look out for.

“Look out for any rocks, kelp, or sea squirts that look a little ‘off’, then check for eyes,” she says.

“Once you spot your first octopus, you can usually spot a few more on the same snorkel. It just takes getting your brain to recognise them.

“I didn't realise there were two octopuses in this photo – I thought it was just the one,” she says. “I spotted the second one in the photo, not in the water!”

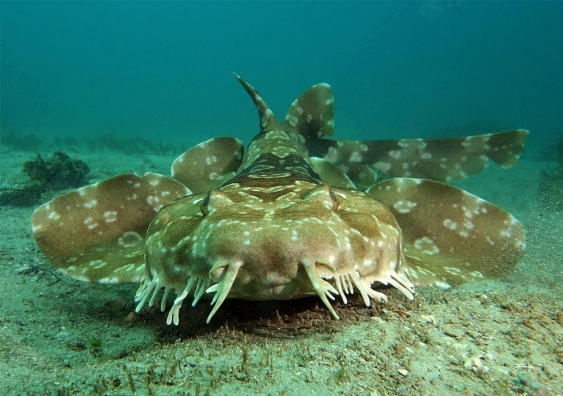

The low-dwelling wobbegong shark is known for its majestic tasselled beard. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

Wobbegongs are flat, bottom-dwelling sharks that live in shallow water. They’re famous for their unique tasselled beards, which act as sensory barbs.

“They are just gorgeous!” says Ms Thayanne Lima Barros, a marine biologist and PhD Candidate at UNSW Science researching the impacts of bushfires on estuaries.

Wobbegongs are often called ‘carpet sharks’ due to the unique symmetrical markings on their backs. The mottled patterns can act as camouflage, helping them stay hidden among rocks and give them an edge for finding prey.

“It’s always a great surprise whenever I see one of them,” says Ms Lima Barros. “Normally, I’m just snorkelling around, looking for weird-looking invertebrates when I see them.”

There are 12 species of wobbegongs, with the two largest types – banded and spotted – commonly found in NSW.

While not usually considered dangerous to humans, wobbegongs have been known to attack if disturbed. Swimmers must take care not to step on or go too close to wobbegongs.

“I’m fascinated by Australia's Biodiversity,” says Ms Lima Barros, who hails from Brazil. “I see wobbegongs as an exotic Pacific Ocean creature.”

Fellow PhD candidate Ms Steinberg suggests looking for wobbegongs at Gordons Bay in Coogee or Shelly Beach in Manly.

“Wobbegongs will be around all summer, but they usually like to hide,” she says.

“At Gordon's Bay there are two large boulders with lots of nooks and crannies for sharks to hide in – I call it ‘wobbegong rock’. If you ask a local, they can probably point it out to you.”

White's seahorse – also known as the Sydney seahorse – can be found across the east coast of Australia. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

White's seahorse, also known as the Sydney seahorse or Hippocampus whitei, are native to the east coast of Australia. They grow to about 16 centimetres and come in different colours, which they can change depending on their mood or habitat.

“The male carries babies during pregnancy – over 100 of them,” says marine biologist and researcher, Dr Steph Gardner.

“Their breeding season is over summer, so if you look close enough you may be lucky to see a pregnant male.”

Male seahorses can be spotted by the pouch on their belly. They can reproduce up to eight times during breeding season, which runs from September to February.

Ms Gardner, who was recently named an Australian Superstar of STEM, usually spots the seahorses along the artificial swimming nets underneath the jetty at Chowder Bay in Mosman.

She recommends practicing your breath holds to stay underwater long enough to spot them.

“I like diving down, then staying motionless and focusing on the nets to see if I can see a little seahorse hanging onto the net with its tail.

“Depending on the direction of the sun, you may even be able to spot the silhouette of the seahorse in the gap of the net – that's one of my favourite sights!”

Hey, tough guy. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

Cuttlefish – or ‘chameleons of the sea’ – have the ability to rapidly change their skin colour. This can help them camouflage, ward off predators, and even communicate with other cuttlefish.

“Like all cephalopods (including squid and octopus), cuttlefish are one of the most intelligent invertebrates on earth,” says social ecologist Mr John Turnbull, a PhD candidate researching environmental stewardship and the impact it has on marine life.

“You can tell when by watching the way cuttlefish interact with you and each other, and by their amazing ability to change colour and texture.”

The reddish-brown mourning cuttlefish pictured above changed colour – within seconds – to the silver pictured here. Photo: John Turnbull / marineexplorer.org

Sydney is home to three cuttlefish species: the giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama), the mourning cuttlefish (Sepia plangon) and reaper cuttlefish (Sepia mestus). Giant and mourning cuttlefish can be found while snorkelling, but the reaper cuttlefish can usually only be found while SCUBA diving.

The Australian giant cuttlefish is the largest cuttlefish in the world. They can grow up to 50 centimetres long and weigh up to 10 kilograms.

“One of the best places to see giant cuttlefish is the sanctuary zone at Shelly Beach, Manly,” says Mr Turnbull.

“Smaller mourning cuttlefish can be found in seagrass and under the jetty at places like Clifton Gardens.”

Lucky swimmers might be able to see mourning cuttlefish change colour. Within seconds, they can change from a brown camouflage mode to a silvery ‘travel’ mode.

“Nudibranchs – the teeny-tiny slugs of the sea – are a real underwater treasure,” says marine and behavioural ecologist, Mr Niki Hubbard.

“They are usually tiny but make up for lack of size with their magnificent colours and patterns.”

Nudibranchs are a group of jelly-bodied molluscs known by their vibrant appearance. The colourful creatures are also hermaphrodites, with the ability to mate with any other member of their species.

There are over 3000 known nudibranch species worldwide and around 700 in Australia. Nudibranchs can be tricky to spot – but finding them is all part of the fun.

“It can be so rewarding to spot that tiny flash of colour making its slow and steady way across one of the rocky reefs around Sydney,” says Mr Hubbard, who is currently studying the impact of artificial light on coastal ecosystems for his PhD.

He suggests looking for nudibranchs in one of Sydney's many tidepools or while snorkelling in the shallows just off a rocky shore.

“Nudibranchs can be as small as a few millimetres in length, so you really need to look hard and explore their worlds up close,” says Mr Hubbard. “Try looking on rock faces just beneath the surface of the water.

“Many nudibranchs and sea slugs tend to have a favourite food, so a bit of prior research before your snorkel can help to narrow down your search.

“Finding their favourite sponge snack, for example, can definitely increase your chances of spotting nudibranchs hanging around.”

When research assistant Ms Madelaine Langley emerges from the water after a snorkel, passersby often stop to ask her if she saw anything exciting.

They usually think she is joking when she responds: lots of seaweed!

“Most of us can appreciate the beauty of the tall eucalypts as we go bushwalking over the summer,” says Ms Langley. “We admire the way the light shines through the foliage, the way they sway in the wind, and the animals that call them home.

“I hope people can apply that same appreciation to our underwater forests this summer, which provide similarly crucial habitat.”

Ms Langley’s favourite type of underwater forest is formed by the golden-green Phyllospora comosa, commonly known as crayweed. The species became locally extinct in Sydney in the late 20th century, but Ms Langley is part of a team of scientists trying to change that.

“Operation Crayweed, run by UNSW and the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, is transplanting crayweed back to the reefs where they used to thrive,” she says. “We started by restoring small patches of crayweed from nearby healthy forests just outside Sydney and are now starting to see crayweed spreading hundreds of metres away.”

The first sign of this spread is the appearance of crayweed babies, or ‘craybies’. Craybies appear nestled below existing seaweed canopy a few months after re-planting.

“Craybies may look insignificant, but to me these tiny fronds represent resilience, growth and hope in a sea of uncertainty,” says Ms Langley, who suggests looking for craybies at Shelly Beach, Freshwater, North Bondi and Malabar.

“Swim along the rocky reef until you locate the restoration mats,” she says. “On these mats you will find crayweed ‘transplants’ attached with rubber materials. Work outwards from here, checking underneath nearby seaweed canopy for craybies.”

Operation Crayweed want to hear about any crayweed sightings this summer. To report a sighting, contact the team via their website or iNaturalist page.

“Octopuses are especially fun because they are so hard to spot,” says marine scientist and coral researcher Ms Rosie Steinberg, who is currently researching the ecology of soft corals for her PhD.

The Sydney octopus, also called the ‘gloomy octopus’, is typically grey or brown with orange-rust red arms. These arms – which can span up to two metres – help the octopus crawl on rocks or to propel through water.

Octopuses can also be territorial, defending their lair during the day and feeding on prey at night.

While there aren’t any tricks to finding octopuses (“They go where they please!” says Ms Steinberg), there are some things you can look out for.

“Look out for any rocks, kelp, or sea squirts that look a little ‘off’, then check for eyes,” she says.

“Once you spot your first octopus, you can usually spot a few more on the same snorkel. It just takes getting your brain to recognise them.

“I didn't realise there were two octopuses in this photo – I thought it was just the one,” she says. “I spotted the second one in the photo, not in the water!”

Wobbegongs are flat, bottom-dwelling sharks that live in shallow water. They’re famous for their unique tasselled beards, which act as sensory barbs.

“They are just gorgeous!” says Ms Thayanne Lima Barros, a marine biologist and PhD Candidate at UNSW Science researching the impacts of bushfires on estuaries.

Wobbegongs are often called ‘carpet sharks’ due to the unique symmetrical markings on their backs. The mottled patterns can act as camouflage, helping them stay hidden among rocks and give them an edge for finding prey.

“It’s always a great surprise whenever I see one of them,” says Ms Lima Barros. “Normally, I’m just snorkelling around, looking for weird-looking invertebrates when I see them.”

There are 12 species of wobbegongs, with the two largest types – banded and spotted – commonly found in NSW.

While not usually considered dangerous to humans, wobbegongs have been known to attack if disturbed. Swimmers must take care not to step on or go too close to wobbegongs.

“I’m fascinated by Australia's Biodiversity,” says Ms Lima Barros, who hails from Brazil. “I see wobbegongs as an exotic Pacific Ocean creature.”

Fellow PhD candidate Ms Steinberg suggests looking for wobbegongs at Gordons Bay in Coogee or Shelly Beach in Manly.

“Wobbegongs will be around all summer, but they usually like to hide,” she says.

“At Gordon's Bay there are two large boulders with lots of nooks and crannies for sharks to hide in – I call it ‘wobbegong rock’. If you ask a local, they can probably point it out to you.”

White's seahorse, also known as the Sydney seahorse or Hippocampus whitei, are native to the east coast of Australia. They grow to about 16 centimetres and come in different colours, which they can change depending on their mood or habitat.

“The male carries babies during pregnancy – over 100 of them,” says marine biologist and researcher, Dr Steph Gardner.

“Their breeding season is over summer, so if you look close enough you may be lucky to see a pregnant male.”

Male seahorses can be spotted by the pouch on their belly. They can reproduce up to eight times during breeding season, which runs from September to February.

Ms Gardner, who was recently named an Australian Superstar of STEM, usually spots the seahorses along the artificial swimming nets underneath the jetty at Chowder Bay in Mosman.

She recommends practicing your breath holds to stay underwater long enough to spot them.

“I like diving down, then staying motionless and focusing on the nets to see if I can see a little seahorse hanging onto the net with its tail.

“Depending on the direction of the sun, you may even be able to spot the silhouette of the seahorse in the gap of the net – that's one of my favourite sights!”

Cuttlefish – or ‘chameleons of the sea’ – have the ability to rapidly change their skin colour. This can help them camouflage, ward off predators, and even communicate with other cuttlefish.

“Like all cephalopods (including squid and octopus), cuttlefish are one of the most intelligent invertebrates on earth,” says social ecologist Mr John Turnbull, a PhD candidate researching environmental stewardship and the impact it has on marine life.

“You can tell when by watching the way cuttlefish interact with you and each other, and by their amazing ability to change colour and texture.”

Sydney is home to three cuttlefish species: the giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama), the mourning cuttlefish (Sepia plangon) and reaper cuttlefish (Sepia mestus). Giant and mourning cuttlefish can be found while snorkelling, but the reaper cuttlefish can usually only be found while SCUBA diving.

The Australian giant cuttlefish is the largest cuttlefish in the world. They can grow up to 50 centimetres long and weigh up to 10 kilograms.

“One of the best places to see giant cuttlefish is the sanctuary zone at Shelly Beach, Manly,” says Mr Turnbull.

“Smaller mourning cuttlefish can be found in seagrass and under the jetty at places like Clifton Gardens.”

Lucky swimmers might be able to see mourning cuttlefish change colour. Within seconds, they can change from a brown camouflage mode to a silvery ‘travel’ mode.