The secrets of 3000 galaxies laid bare

The completion of an Australian-led astronomy project has shed light on the evolution of the Universe.

The completion of an Australian-led astronomy project has shed light on the evolution of the Universe.

The complex mechanics determining how galaxies spin, grow, cluster and die have been revealed following the release of all the data gathered during a massive seven-year Australian-led astronomy research project involving UNSW.

The scientists, including UNSW Science astronomer Professor Sarah Brough, observed 13 galaxies at a time, building to a total of 3068, using a custom-built instrument called the Sydney-AAO Multi-Object Integral-Field Spectrograph (SAMI).

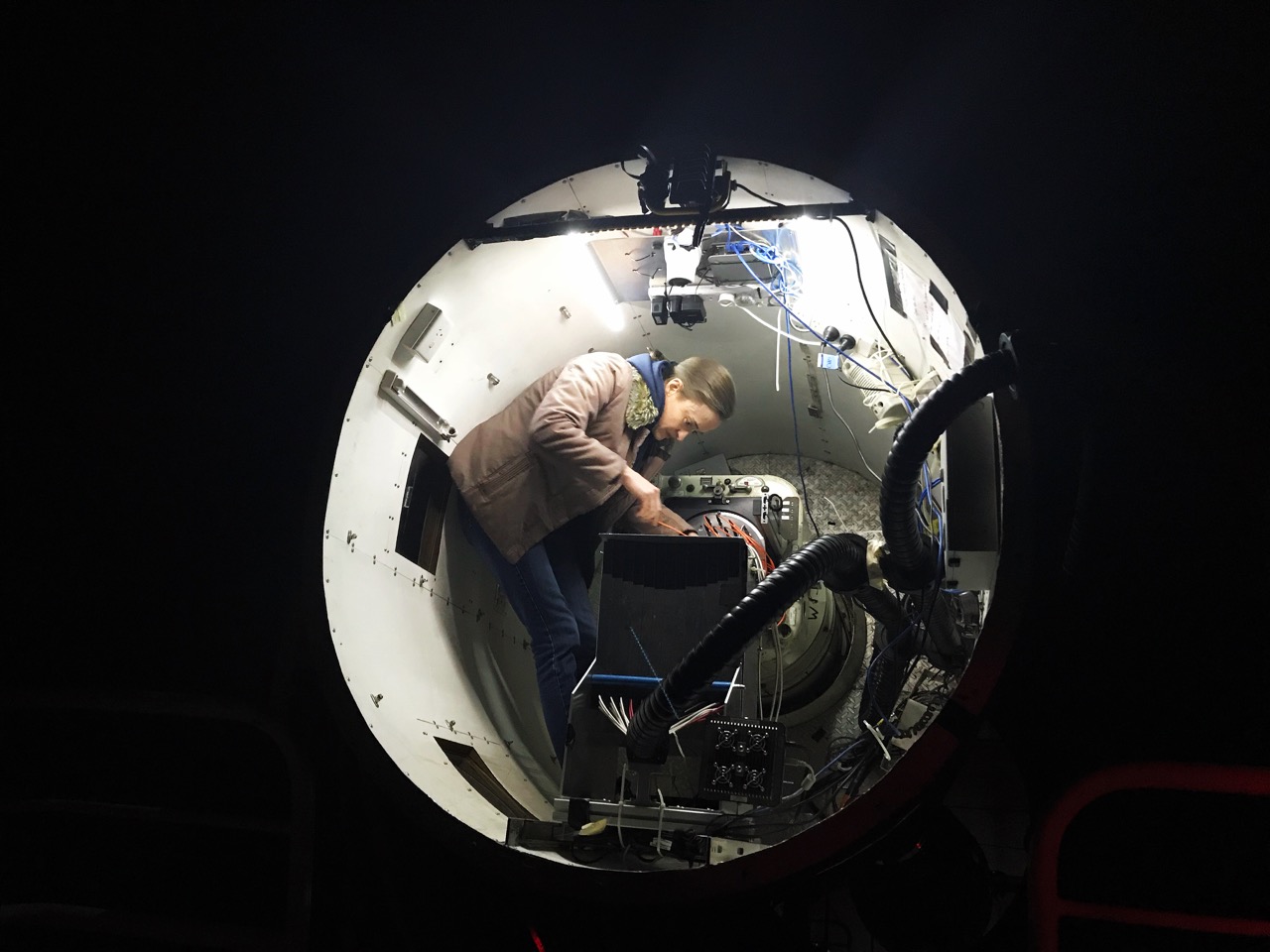

SAMI was connected to the 4-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. The telescope is operated by the Australian National University.

Overseen by the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), the project used bundles of optical fibres to capture and analyse bands of colours, or spectra, at multiple points in each galaxy.

The results allowed astronomers from around the world to explore how these galaxies interacted with each other, and how they grew, sped up or slowed down over time.

No two galaxies are alike. They have different bulges, haloes, disks and rings. Some are forming new generations of stars, while others haven’t done so for billions of years. And there are powerful feedback loops in them fuelled by supermassive black holes.

“The SAMI survey lets us see the actual internal structures of galaxies, and the results have been surprising,” lead author Professor Scott Croom from ASTRO 3D and the University of Sydney said.

“The sheer size of the SAMI Survey lets us identify similarities as well as differences, so we can move closer to understanding the forces that affect the fortunes of galaxies over their very long lives.”

The survey, which began in 2013, has already formed the basis of dozens of astronomy papers, with several more in preparation.

A paper describing the final data release – including, for the first time, details of 888 galaxies within galaxy clusters – was published today on the arxiv pre-print server and in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“The nature of galaxies depends both on how massive they are and their environment,” Prof Croom said.

“For example, they can be lonely in voids, or crowded into the dense heart of galactic clusters, or anywhere in between. The SAMI Survey shows how the internal structure of galaxies is related to their mass and environment at the same time, so we can understand how these things influence each other.”

Research arising from the survey has already revealed several unexpected outcomes.

UNSW’s Prof Brough showed that the amount of rotation a galaxy has is primarily determined by its mass, with little influence from the surrounding environment.

Another group of astronomers showed that the amount of a galaxy’s spin depends on the other galaxies around it, and changes depending on the galaxy’s size.

A second looked at galaxies that were winding down star-making, and found that for many the process began only a billion years after they drifted into the dense inner-city regions of clusters.

“The SAMI Survey was set up to help us answer some really broad top-level questions about galaxy evolution,” co-author Dr Matt Owers from Macquarie University said.

“The detailed information we’ve gathered will help us to understand fundamental questions such as: Why do galaxies look different depending on where they live in the Universe? What processes stop galaxies forming new stars and, conversely, what processes drive the formation of new stars? Why do the stars in some galaxies move in a highly ordered rotating disk, while in other galaxies their orbits are randomly oriented?”

“The survey is finished now, but by making it all public we hope that the data will continue to bear fruit from many, many years to come,” Prof Croom said.

“The SAMI Survey provides one of the most complete samples for exploring how galaxies change depending on where they live. My PhD student Giulia Santucci and I are still exploring interesting questions about the internal properties of galaxies in this survey,” Prof Brough said.

“The next steps in this research will make use of a new Australian instrument – which we’ve called Hector – that will start operation in 2021, increasing the detail and number of galaxies that can be observed,” Co-author Associate Professor Julia Bryant from ASTRO 3D and the University of Sydney said.

When fully installed in the AAT, Hector will survey 15,000 galaxies.

The final data release paper has 41 authors, drawn from Australia, Belgium, the US, Germany, Britain, Spain and The Netherlands.

The full data set is available online through Australian Astronomical Optics (AAO) Data Central.