Politicians need expert help to change culture of sexual violence, not yet another review

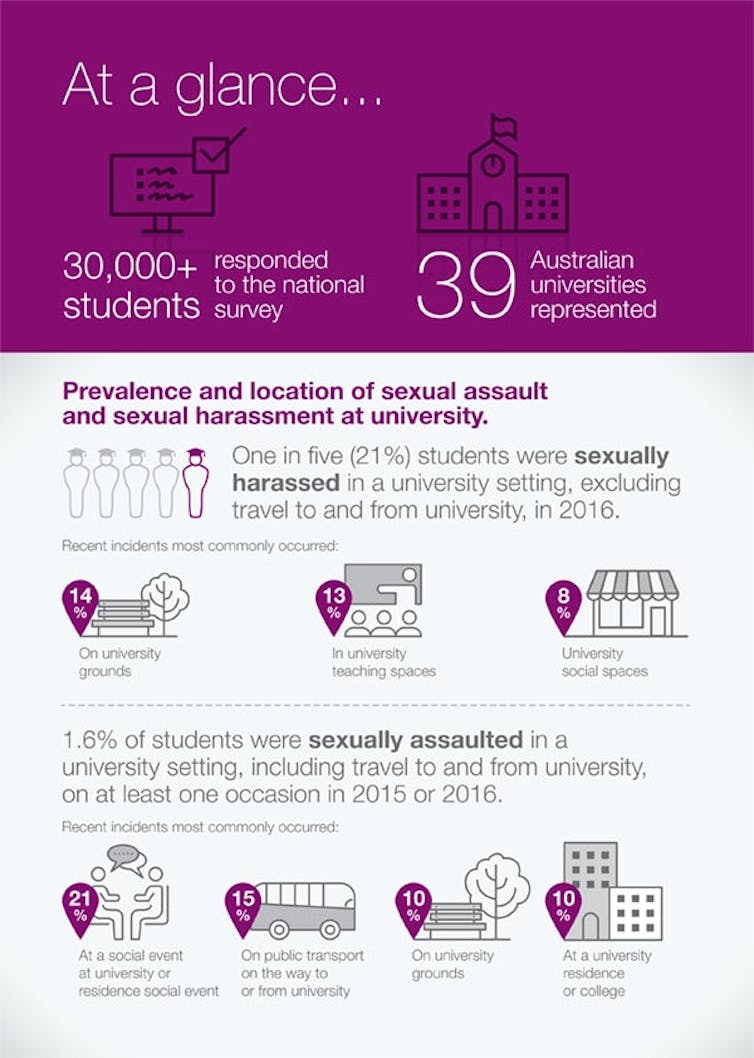

Universities are a step ahead in having adopted a number of practical changes, but it's clear transformative cultural change in our institutions requires all the expertise they can muster.