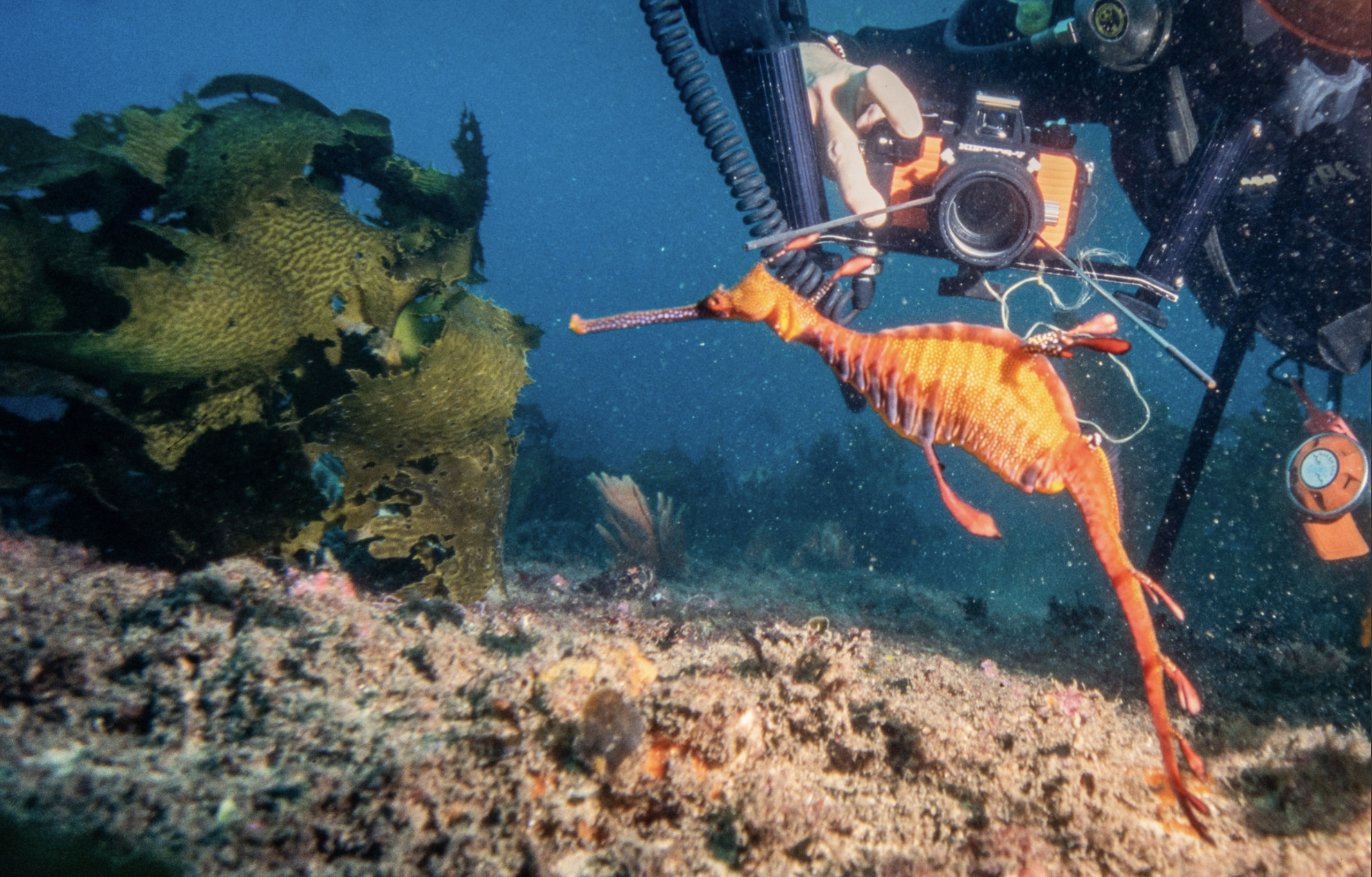

Old diving photos wanted for underwater research

Scientists from UNSW Sydney hope to document how marine life has changed at dive sites over the years by using photos and observations from the public.

Scientists from UNSW Sydney hope to document how marine life has changed at dive sites over the years by using photos and observations from the public.

Divers in Sydney and the NSW North Coast are being asked to contribute their old and new diving photos, videos, observations and knowledge to a new UNSW Sydney research project.

It is hoped that the images and recollections collected for the In Bygone Dives project will lead to a better understanding of how the underwater world has changed over recent decades.

“Old dive photos hold a wealth of information, and potentially valuable scientific data on the past health of reefs and the species that were present,” lead researcher and PhD candidate in the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences at UNSW Sydney, Chris Roberts says.

“We can use these photos and observations to document how the marine life at dive sites has changed from the past and also to monitor them into the future,” Mr Roberts says.

Mr Roberts will launch the project at the Manly Seaweed Forests Festival this Sunday, April 18.

The In Bygone Dives project is currently focusing on two study regions, Sydney and the NSW North Coast, but may expand to include more regions at a later stage.

The researchers are particularly interested in photos or videos from these Sydney dive sites: Shelly Beach, Fairy Bower, Camp Cove, Fairlight, Clifton Gardens, Gordons Bay, Clovelly Pool, Shark Point, Bare Island, Kurnell and Ship Rock.

They are also keen to track the timing and location of the loss of underwater forests such as kelp from NSW North Coast, between Byron Bay and Tweed Heads.

“We also hope to understand the southward range extension of tropical herbivorous fish, which may have contributed to the Kelp loss,” UNSW marine ecologist, Associate Professor Adriana Vergés says.

Many underwater changes may have gone undocumented as they occur over time scales that are beyond most scientific studies, she says.

However, many recreational divers will have likely observed and recorded such changes over many years or even decades while visiting their favourite dive sites.

Currently most of this valuable information is stored in personal archives and collections, often largely unused.

Mr Roberts is hoping to motivate people to recover these valuable underwater photos from forgotten drawers or hard-drives so that they can be used for research.

Project co-leader Professor Alistair Poore from UNSW Science says that by obtaining a better understanding of the past, this project aims to unlock information that can help conserve reefs into the future.

“Recreational divers gathering and sharing photographs and videos, combined with image recognition technology, could enable increased monitoring of marine life at many reefs rarely visited by professional scientists” Prof. Poore says.

Divers who want to contribute photos to the project should upload them to the In Bygone Dives iNaturalist page.