The Mitchells vs The Machines shows 'smart' tech might be less of a threat to family bonds than we fear

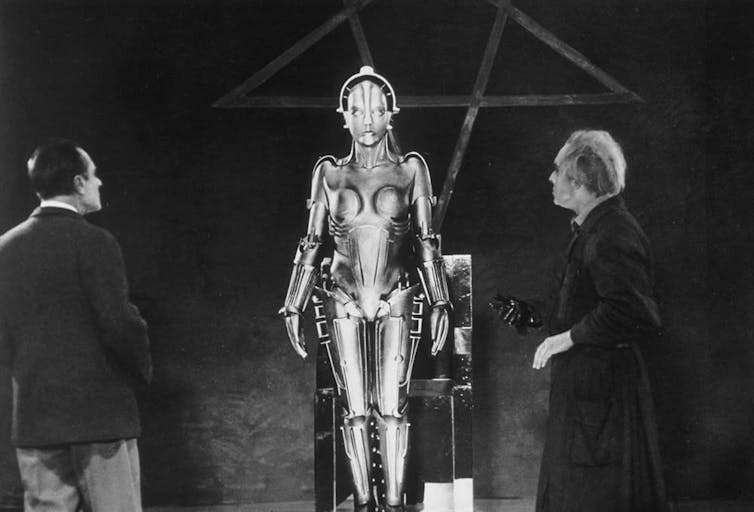

Fictional screen robots have long represented our fear of technology. A new animated family film combines this trepidation with many parents' fear of losing offline connection with their kids.