Can the law truly protect consumers from data profiling?

It is clear that consumers expect the law to protect them when it comes to how their data is collected, shared and used. But is the law enough?

It is clear that consumers expect the law to protect them when it comes to how their data is collected, shared and used. But is the law enough?

As avid Australian consumers, many of us think our personal information is protected by the Privacy Act. However, what some UNSW experts have found in their research is that the effectiveness of this regulation is severely compromised by the drafting of the Privacy Act, and inadequate enforcement.

“The Privacy Act is drafted very poorly. Enforcement agencies also have few powers and few incentives to enforce it well,” says Dr Kayleen Manwaring, who specialises in legal implications of the use of emerging technologies for consumers and businesses.

Consumers’ perception, she says, is also a real problem.

With the omnipresence of digital platforms such as Google and Facebook in our daily life, many consumers consent to providing their personal data to commercial entities.

“But this is not because they are not worried about their privacy. It’s because they perceive that they don't have any real alternative,” Dr Manwaring says.

‘Consent’ usually involves consumers accepting a set of take-it-or-leave it standard form terms – with little comprehensible information provided about how their data is collected and disclosed by the business providing the product or service.

Loopholes in the Privacy Act – which can be quite technical – have also been extensively used by commercial entities when drafting privacy policies in a vague and open-ended manner. This in turn has made it more difficult for people to change their privacy settings, or to have any choice in changing their privacy settings.

“There are deeply embedded privacy settings that are often difficult to change, and in some cases have been misleading, just like in the most recent court case with Google,” Dr Manwaring says.

The use of these practices by data brokers and suppliers of adtech (advertising technology) is particularly concerning. Big data mining, consumer profiling and behavioural advertising all drive vastly increased collection, use and transfer of personal data.

“Consumers have no reasonable way to discover the hundreds, often thousands, of companies who are receiving data about them as a result of their online browsing and purchases.

“Companies have effectively kept the nature of this profiling and disclosure hidden from us as consumers, while our lives are made increasingly transparent to those companies,” says Dr Katharine Kemp, an expert in data privacy regulation. Dr Kemp is a co-author of the report titled ‘(mis)Informed Consent in Australia’ along with Dr Manwaring and UNSW Business School Associate Professor Rob Nicholls.

Where businesses have been misleading or deceptive in privacy matters, the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) has recently been of some benefit. For example, in April this year the Federal Court held that Google had breached the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) by misleading Android users about whether Google saved user location history collected on their mobile devices.

“This was a promising development for consumers, but any deterrent effect is uncertain until any appeals processes are exhausted and a penalty decision is made, especially on business entities with vast resources like Google,” Dr Manwaring says. Monetary penalties under the ACL can go up to A$10 million or 10% of Google’s local turnover.

In the report, Dr Manwaring explores how businesses deal with consumer data and whether it can truly protect individuals in Australia. This is assessed against current business practices, consumer expectations and enforcement activities, as well as general economic, social and behavioural factors.

To safeguard consumers’ privacy, the report suggests that changes have to be made not only to the drafting of the Privacy Act, but also to enforcement procedures. Some examples of these include changes to key definitions, making the OAIC’s non-binding guidelines on informed consent mandatory, prohibiting concerning data practices such as bundling consents, a direct right of action for individuals, and extended investigative powers, remedies and resources for the regulator.

Other areas such as website design, and better integration of laws and enforcement bodies can also help.

“We don't only have the Privacy Act that applies, but the ACL as well. So, we're looking at how these two Acts need to integrate better and how relevant enforcement bodies also need to work better together.”

Dr Manwaring says this research finding is particularly relevant now in the lead-up to the second round of review of the Privacy Act later this year.

“It’s a fact that a couple of platforms are being prosecuted for breach of data protection, breach of consumer rights in relation to data protection, although it's mostly been under the ACL.”

The report highlights how consumers are unaware of the extent of commercial dealings with their personal data.

“It is clear that people often do not understand what data about them is being collected by businesses and to whom it is being disclosed. However, they are very concerned about the potential for misuse of personal information.”

“They frequently feel helpless about controlling commercial use and disclosure of personal information; and expect both reputable companies and the government to protect the rights of individuals,” Dr Manwaring says.

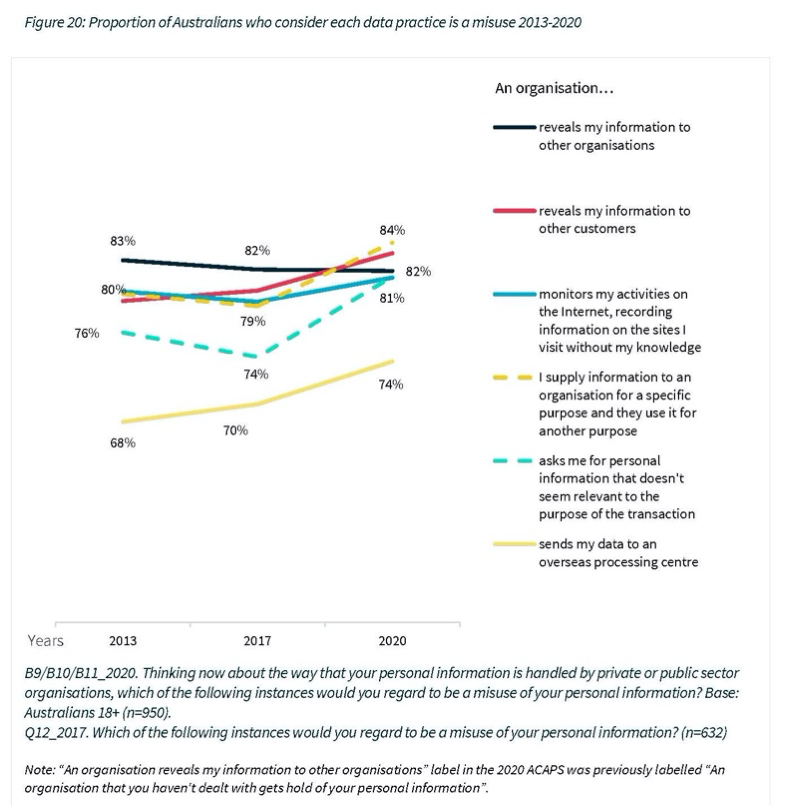

For example, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) found that most Australians consider the following digital data practices to be a misuse of personal information:

However, this ‘misuse’ is common practice amongst many commercial entities. In many cases, they wouldn’t ask consumers for consent. Even in instances where the law does require consent, the consumer consent obtained is not informed, non-negotiable, and is subject to how the business defines ‘consent’.

The research report identified that the use of standard form contracts actually increased information asymmetries and power imbalances between the consumer and service provider.

“This shows a significant disconnect between actual digital data practices by businesses and the expectations of consumers.”

Another key finding is that the consent provisions of the Privacy Act, combined with weak enforcement practices by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), do not meet consumer expectations. The report also pointed out significant gaps in the ACL that could prevent consumers from seeking protection against misuse of their data. For example, unfair data practices by a business may in many circumstances escape liability under all of the following ACL provisions: misleading and deceptive conduct, unconscionable conduct, and unfair contract terms.

The use of bundled consents, vague, open-ended privacy policies, collection through unidentified third parties, and ineffective opt-outs made it all more confusing for consumers to understand the full implications of ‘consent’.

Fundamentally, it is clear that an effective new privacy framework needs an integrated approach that collectively draws on Australia’s competition, consumer and privacy laws.

“For this approach to be truly effective, collaboration between enforcement agencies, competition authorities, information commissioners, and consumer protection agencies will need to be coordinated,” the report says.

“In a more specific sense, a series of solutions … have been proposed, which together will serve to enhance the protection provided through Australia’s privacy framework and the nation’s reputation on the world stage as a country that values a human being’s right to privacy and protection.”

But the reality is that Australia is still lagging behind other countries in terms of setting up its privacy best practice standards. Until Australia has a “satisfactory proposal for ensuring that standards are improved to international best practices, we will continue to suffer as a nation economically, professionally and personally”.

This project was funded by the International Association of Privacy Professionals – Australia/New Zealand Chapter Inc (iappANZ) as part of its legacy grants scheme for research projects advancing professionals in the privacy and data industries. The views expressed in this article and the report do not necessarily reflect the views of iappANZ.