Professor Stephen Foster has more than 60 years of UNSW Engineering in his DNA – so it’s no surprise that he is excited to lead the Faculty into the 2020s.

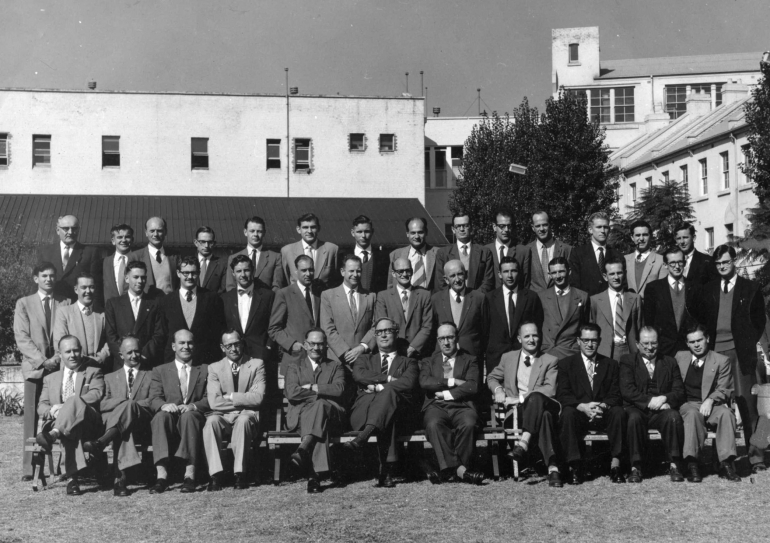

Prof. Foster was officially appointed Dean in April after a 15-month spell in an acting capacity, but he can trace his roots on campus all the way back to 1959 via his father who was an Associate Professor of Civil Engineering.

Indeed, one of the very first photographs taken of the School of Civil Engineering at its Kensington Campus location, after moving from Ultimo, features the senior Foster.

Fast forward more than six decades and the world, as well as the University and the Faculty, has changed enormously.

But Prof. Foster believes the fundamental issues facing society today, and which should be foremost in the mind of modern engineers, remain remarkably similar.

And he is confident the people within UNSW Engineering can continue to do great things, now and well into the future, to help address those major issues.

Q: What do you think are the biggest issues facing engineers in the next 10 to 20 years?

A lot of these issues are the same ones that have been spoken about and discussed for the past 40 years and, indeed, written of by a former Dean of Engineering Professor Noel Svensson.

They are things such as climate change, sustainability, conservation of natural resources, automation while retaining employment opportunities, affordable healthcare, protection from the effects of natural disasters, and the elimination of hazards at work and in the home.

None of the issues really change, just perhaps the emphasis we place on them, or the political will to make them happen.

We have seen throughout the COVID challenge how the research and industrial world, with governments and policy makers, can make enormous strides in vaccine technologies, technologies and solutions driven by science-based decision making to an extent, and at a speed, never before achieved.

We have been equivocating for far too long on rolling out solutions to our changing climate and adapting our industries and livelihoods to meet this challenge.

Many countries around the globe, as well as Australian States and Territories, have announced their objective of sector wide carbon neutrality by 2050 – it is my view that we have in place now sufficient knowledge and understanding on how this can be achieved, and the research needs for the final solutions identified to the extent that within 10 years from when we start, we can have in place the pathway to achieve this.

And we have done this before, in the phasing out of CFCs to address atmospheric ozone. No doubt that this is a much greater challenge than that, but one that we cannot afford to fail in.

Many of my colleagues are sceptical of this view, and maybe they are right to be so, given history. But for me, we just need to start – for every year that we delay, the harder it becomes and, taken as a whole, we know what needs to be done.

That topic gets talked about a lot, but we also must think about privacy and cybersecurity which becomes ever more important as we become more and more reliant on technology in an interconnected world.

Nowadays cyber-criminals can enter our lives, bypassing physical boundaries, and shamelessly target our most vulnerable .

Healthcare has obviously come to the forefront recently with COVID and here in our region we’ve seen the effect of many natural disasters in the past couple of years with drought, bushfires and floods; internationally, earthquakes in Europe and Asia and, most recently, magma flow in Africa, so that always remains important.

But we also need to talk about equity and diversity and assisting those that need the most help, especially our underprivileged. And, in those areas engineering has a vital role to play.

That challenge is immense and not easily solved, otherwise we would have done it already, so there is a lot of work to do.

In Australia, we need to work with the First Nations groups and the rural and regional communities to deal with various issues that often go back generations. And that means bringing together people and resources from across the University, across government and across life, and listening to our communities to really understand the complexity of those issues.

Q: What are the existing strengths here at UNSW Engineering?

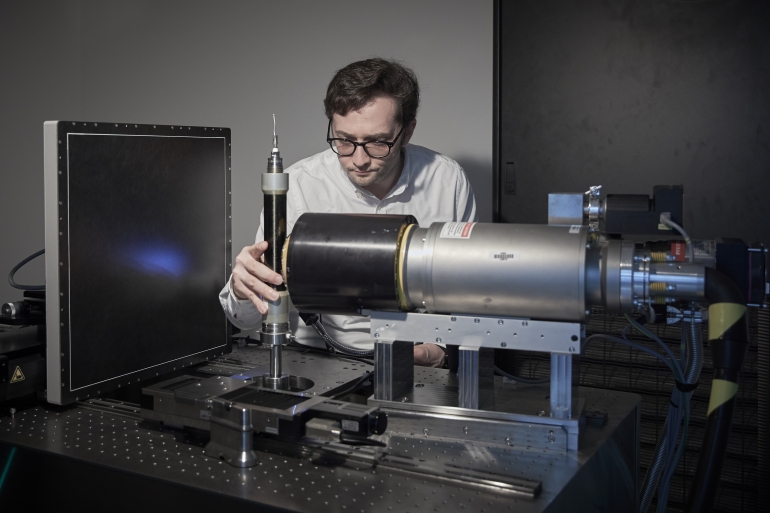

We lead in many of the areas concerning these big issues. For example, we lead in photovoltaics; we lead in the construction materials sector; we have great people working in biomedical engineering and food security; we’ve just set up the Institute for Cyber Security. And, we are leading in the new world of Quantum computing, to name just a few.

Because we are a Faculty of scale and we have Centres of Excellence in and across our Schools in those, and other, core areas, we will continue to play a big role in solving our great societal challenges.

Engineers progress change. And what academic engineers do is give society the tools to progress that change in an economic way.

We’re the number one university for engineering in the country and have been for some time and in many fields we are top 20 and 50 in the world.

In terms of our students, we want the best and brightest to choose to come to UNSW. But we also have to show them that we are providing the best quality education and the chance to learn from, and work with, the leaders in society and the people who are really helping to make the changes.

And I know we have those leaders here, so if students have that ambition to grow and become the person making those big changes for society in five or ten years then I believe this is the best place to be.

The most important thing we do at UNSW is teach our students to learn how to learn. We can’t teach them absolutely everything that they will need through the totality of their professional life as an engineer or computer or food scientist in the three or four or five years that they are here, and in any case we all know that change is inevitable. And, then when things do change in five or 10 or 20 years, they will have the ability to adapt quickly and be at the forefront of the new age.

Q: How has UNSW changed since you started here as a Teaching Fellow in 1987?

I’ve seen it grow and develop so much over that period and I think the way the University has changed also reflects the way society has changed.

Going back 30 years, or so, each individual School, and even each individual Faculty, was quite insular in terms of solving the problems in their own area and not so much working collectively on solving the big issues, together.

That has very much evolved, to the extent that we are now at a point where it’s not just one School, or one Faculty, or even one University trying to solve these major societal problems – with multidisciplinary – pan University teams needed and, indeed, coming together.

Where we need to keep making progress is the engagement between Universities, policymakers, Governments and industry. We are not yet at the point where those core groups are collectively in the room together trying to advance the state of the nation.

I don’t believe we will be truly successful until that happens, until everyone is on the same page, working to the same agenda, trying to solve these big issues collaboratively.

Q: What are your aims and ambitions for UNSW Engineering over the next 5 to 10 years?

By 2031 I hope that we would have helped solve the energy side of the sustainable economy. So that we have grid wide solutions in place.

We will also have played a major role in solving the issue of how the wider industrial sector of our economy deals with carbon and, as a society, be a long way down the track towards a 2050 carbon neutrality goal.

Our work in cybersecurity will help people feel safe in their homes and in their online interactions. And our contributions in quantum computing, the space economy, AI and robotics will be leading the way to even greater discovery.

Our Biomedical engineers, and the work we do here, will help sustain and improve the health of our communities and move us into an era where telehealth is the new norm. And food security and social justice and equity become ever increasingly concerns of the past.

The expertise we have in all our Schools is outstanding and they are all aligned to help address those major issues in society. I don’t think we’ve ever been in a better place, thanks to the strategy we have where everyone – the Faculty, the Schools and individuals – has that big picture view and the vision needed to help deliver big solutions.

Q: What have you already learned during your time as Acting Dean?

I was obviously extremely familiar with many aspects the Faculty already, given the fact I was previously Head of the School of Civil & Environmental Engineering and Acting Head of the School of Minerals & Energy Resources Engineering.

But I think through this role gave me greater insight into the brilliant work we do in so many areas across the Faculty and with all the other Faculties and realising the potential for collaborations where appropriate, which is an area where we can really evolve.

I came into this role in 2020 which was a challenging year for many reasons, not least with COVID and the effects that had on our university, as well as across the education sector.

But I think being an engineer helped to deal with that. As an engineer is about finding solutions to problems. With great challenge comes grand solutions, and major events spark accelerated advancement.

In 2019 we had already recognised that there likely needed to be some transformation in the way we delivered education to our students, but in a normal environment there is always going to be some resistance to change and to dealing with the logistics.

But because of COVID we were forced to change, and in the space of two weeks we made this remarkable switch from face-to-face to online delivery. I’m not saying that there is not a whole lot of work that has yet to be done, but I simply do not see us going backwards from what we have learned during this incredible period of educational advancement. And what the new on-campus experience is for our students remains very much work in progress.

I think the challenge going forward from here is to redefine what the university experience is for students, not so much in content delivery because we have proved we can do that effectively and efficiently, but to increase the personal engagements and continue to develop ideas such as vertically integrated projects, where undergraduates and postgraduates work together on projects with our best professors.

I think there is going to be a new model of what a university education actually is. And we need to be leading that too – as we already are.