OPINION | We're all better off if ASPI has time to think

This weekend marks the 20th anniversary of the first council meeting of the government-funded think tank, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

This weekend marks the 20th anniversary of the first council meeting of the government-funded think tank, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

This weekend marks the 20th anniversary of the first council meeting of the government-funded think tank, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). Established by the Howard government, ASPI was declared an independent strategic policy institute and an alternative source of advice to the Department of Defence. Over the past 20 years, ASPI has championed a range of security causes and its work has had a major impact on national policy.

It was influential in calling for a regional aid mission in the Solomon Islands. Its tracking and analysis of the Defence budget and purchases is widely read and highly regarded. It has prosecuted a closer understanding of Chinese intervention in Australian political and educational institutions, to such an extent that Chinese state media has singled out ASPI as a malign influence. And it ranks as one of the world's best think tanks in a global index.

ASPI, according to its founding director Hugh White, now an ANU strategic studies professor, was thought necessary as Defence remained one of the "few remaining bastions of non-contestability in public policy in Australia".

ASPI was not the first government think tank of its kind in Australia. In March 1973, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam delivered a speech outlining his new government's proposed reforms to public administration. After one year in office, and beset with political challenges, Whitlam decried the lack of time for thinking on important national policy. To tackle this problem, he created an in-house think tank, the Priorities Review Staff.

He also announced the changing role of ministerial advisers. Challenging the traditional public service "advice" model, Whitlam spoke of "the present need to develop and maintain new policy initiatives involving people outside the department" by providing ministers "with greater help on the policy side". Whitlam established a precedent for the contestability of advice.

Over the next two decades, new mechanisms for supporting the work of ministers were introduced. First was the hiring of ministerial consultants. In 1985, a relatively young British-born academic - Paul Dibb, based at the ANU - was appointed by an equally young Labor defence minister, Kim Beazley, as a ministerial consultant. The appointment was a solution to an entrenched impasse between the government and the Department of Defence. Dibb's review set a precedent for ministers to appoint external advisers to review Defence functions.

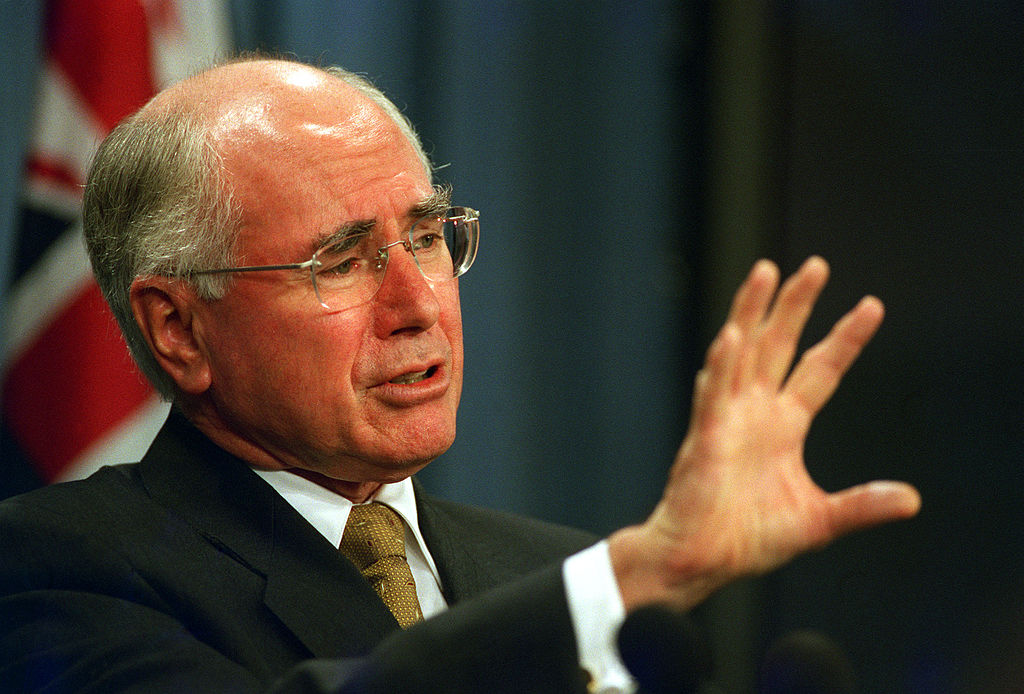

With the election of the Howard government in 1996, more change was to come. While the government had quarantined Defence from spending cuts, it had to prove itself an efficient spender of taxpayers' money. The appointment of Ian McLachlan as Australia's 43rd defence minister was an astute move. McLachlan was to embark on the most radical reorganisation of the Australian Defence Force in 25 years. He identified the provision of advice to government as a key area for improvement, yet Defence was still unwilling to concede the contestability of advice.

McLachlan urged his advisers to develop a proposal for creating a strategic policy institute. He hoped such an institute would stimulate a revitalised debate about defence and security, and that it would prove to be a valuable source of public policy ideas and expertise. It was one of his enduring legacies.

At its 15th anniversary dinner in 2016, past and present ASPI staff and political leaders spoke warmly of ASPI's research capacity, organisational independence, and long-term orientation, but added a surprising call for a change in direction. ASPI's future was questioned by respected Labor thinker, former senator and then-ASPI chair Stephen Loosley. Schooled in the art of politics, Loosley called for the severing of ASPI's formal ties with Defence. He claimed that for ASPI to grow in its second 15 years - and to extend its policy influence outside of Australia - "the RAND model beckons".

I caution against adopting such a model for three reasons. First, like the RAND Corporation, ASPI's research focus has already expanded. It now focuses on defence and strategy, international affairs, cyber security, strategic policing and law enforcement, border security, counterterrorism, and risk and resilience. Second, ASPI was originally to "maintain a very small staff" and was allocated an operating budget of between $2 million and $3 million. ASPI now employs over 60 staff with a $10 million annual operating budget. It is perceived by think-tank academic Diane Stone as being akin to a "small university department". ASPI must be careful not to be consumed by perpetual fundraising. Third, if ASPI continues to grow, it is at risk of burdening its staff with administration and its associated costs.

The proliferation of think tanks over the past 20 years in Australia suggests an ever-increasing need for publicly and privately funded organisations to help do governments' thinking. Given the pressure on cabinet, ministerial overload and modern political processes limiting the discussion of long-term economic and societal issues, "thinking" organisations have secured a permanent seat at the national policy table.

The influence of traditional think tanks on policy development is, however, declining in the face of new competitors and the profile of new media platforms.

Despite its successes, and a broader acceptance of the contestability of advice to government, ASPI is a think tank under pressure. Remaining agile, nimble, and responsive thinkers is paramount. Having no time for thinking could impact on the quality of its own research product and risk reputational harm.

Andrew Blyth is manager of the UNSW Canberra John Howard Prime Ministerial Library and a former chief of staff in the Howard government. He is undertaking doctoral studies in public leadership researching think tanks.

This article was originally published by The Canberra Times.