Does music improve overall health and wellbeing?

The positive health effects of music suggest it’s time to get your ABBA on.

The positive health effects of music suggest it’s time to get your ABBA on.

What’s your favourite genre of music? Do you prefer Bach over Metallica? Or perhaps David Bowie is more your jam than Ed Sheeran?

When it comes to the most impactful music in terms of health and wellbeing, does genre matter? Not really, according to current research. There is clear evidence that listening to the music you like can help improve your mood and decrease anxiety, for example.

Dr Matt McCrary from UNSW Medicine & Health says engaging with music – which includes listening to music, playing an instrument or singing – elicits an emotional response, which also has a physiologic component.

“The specific 'how's' and 'whys' regarding music's ability to elicit this emotional response is still the topic of much debate but it appears to be related to the creation of an emotional connection between musicians, who create sound with an emotional intention, and listeners, who receive this emotional information,” explains Dr McCrary, who is an Adjunct Lecturer at the Prince of Wales Clinical School, UNSW Sydney.

Dr McCrary says the physiologic implications of this emotional response are a broad activation of many brain regions and autonomic nervous system activation – specifically, of the 'fight or flight' (sympathetic) response during most music engagement, followed by increased 'rest and digest' (parasympathetic) activity after the music stops.

“My working hypothesis is that repeatedly engaging with music and eliciting these autonomic nervous system activation patterns increases our ability to respond effectively to stress, which in turn improves our overall health and wellbeing.”

And coming back to whether you prefer contemporary pop, heavy metal or classical music, there is currently no evidence to support whether a particular genre is better than another, just as long as it’s music you enjoy.

“The most impactful music on health and wellbeing appears to be the music that you like the most, as playing and listening to it corresponds to the strongest emotional and physiologic response. For some, this may be classical music, and for others, it may be heavy metal,” says Dr McCrary.

Interestingly, engaging with music elicits similar autonomic nervous system activation patterns that we experience when participating in exercise. However, Dr McCrary says the magnitude of these responses to music is of a lower amplitude when compared to exercise.

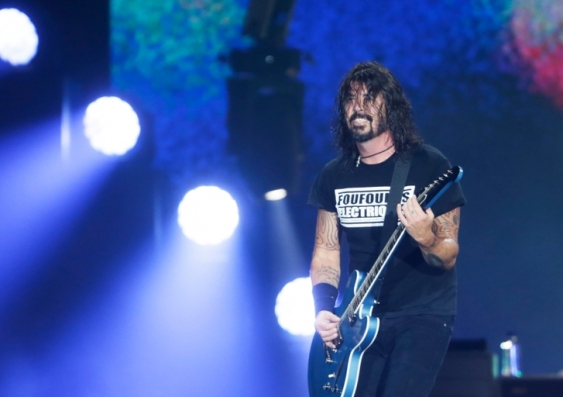

Mozart? Sure. But if listening to the Foo Fighters brings you joy, that also works. There is currently no evidence to support whether a particular genre is better than another, just as long as it’s music you enjoy. Photo: Shutterstock

In a recent paper published in JAMA Network Open, Dr McCrary and his colleagues revealed that repeatedly engaging with music – which could be listening to music, playing an instrument, or singing – has a real, tangible positive impact on our overall health. This tangible positive impact of music appears to be about half the impact of the positive health effects of regular exercise.

“This study provides the first quantitative evidence of clinically significant improvements in wellbeing and health-related quality of life associated with music engagement. Additionally, by focusing on studies that used the SF-36 – the most widely used short-form health survey – this analysis enabled the magnitude of the impacts of music interventions to be compared and contextualised for the first time against established interventions such as exercise and weight loss.”

Based on the findings of the study, Dr McCrary says he was pleasantly surprised to find the impact of music interventions is, on average, tangible, quantifiable, and statistically and clinically significant.

“The most exciting thing about these results is the insights they provide into the potential impact of music on our overall health. For example, exercise is associated with the prevention of 1.6 million annual deaths. If music can have half this impact, we're looking at the prevention of 800,000 annual avoidable deaths. So, the potential here is exciting if we can figure out how to target and maximise music's effects,” explains Dr McCrary.

Read more: Why you should learn a musical instrument

“Previous systematic reviews used narrative methods to synthesize the broad range of, often conflicting, results regarding music's health impact. This is to say, this study aimed to be very direct and quantitative, taking a 'cold', impartial approach to music's effects, and I wasn't sure that the impact of music on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) would be quantifiably significant.”

The researchers acknowledge that the individual variation in results is broad, meaning the impact of engaging with music at an individual level is still unclear. The analysis also couldn't provide any insights into how to optimise music 'prescriptions', for example how long or often to engage with music.

“The practical implication of these limitations is that, while we now have a better sense of the average impact of music interventions, much more work needs to be done to enable music to be reliably prescribed for maximum health benefits in a given individual.”

Dr McCrary says the next big step to realising music's health potential is the creation of a framework to enable music's health effects to be reliably prescribed across individuals.

“This framework has been developed theoretically, adapting key insights from the development of reliable exercise prescriptions. The immediate next step is to empirically test this prescription framework and see if it can consistently produce positive health outcomes in various real-world settings, for example clinical rehabilitation and public health programs. The aim is to begin doing it by the end of this year.”

In the words of the great Swedish supergroup ABBA, thank you for the music.