Sunswift 7: Driving technology forward

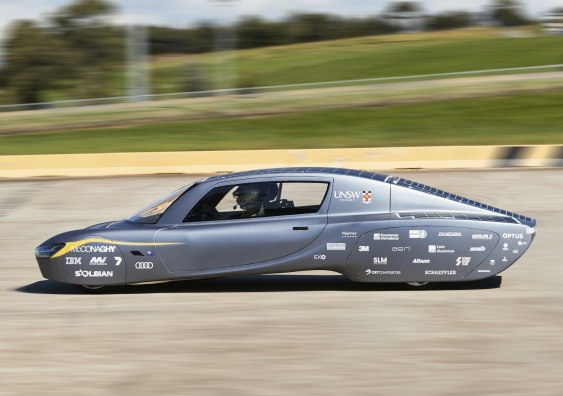

UNSW's latest high-performance solar-powered car, designed and built by students, is now on track for an incredible Guinness World Record attempt.

UNSW's latest high-performance solar-powered car, designed and built by students, is now on track for an incredible Guinness World Record attempt.

When Sunswift 7 lines up to potentially break a new world speed record in December, it won’t just be the culmination of thousands of hours of work by a team of UNSW students over a period of 18 months through the perils of Covid and its associated lockdowns.

Instead, it will be the product of more than 25 years of heritage when it comes to producing high-performance solar-powered racing cars.

Sunswift Racing, which officially unveiled its latest car this week, has been pushing the boundaries of solar vehicle technology since 1996 and enjoyed success in numerous races, most notably the World Solar Challenge, and collected motorsport records along the way.

The seventh car to be produced will aim to set the Guinness World Record for the fastest electric solar car over 1000km at the Australian Automotive Research Centre in Victoria, with the team hoping they can achieve an average speed of over 120km/h for the entire distance.

The Sunswift 7 solar-powered car was built on campus at UNSW Sydney by a team of around 50 students. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

That will be just one reward for many months of hard work designing and building the car, which would have been difficult enough without the additional challenges of the pandemic.

Which is why Sunswift team principal, Professor of Practice Richard Hopkins, is immensely proud of everything the students have achieved just to get the car out onto the track.

“This is the result of the hard work of 50 undergraduate students who are very dedicated, very focused and very talented,” he said.

“They were given the freedom to create. The criteria was simply: build a car that has solar powers and a battery. I had very little influence over what they chose to do within that – I just wanted them to make the best engineering decisions.

“Sunswift 7 is the manifestation of their collective minds, who on day one probably had very little idea what they were doing. And now to produce this amazing car is just insane.

“Let’s remember, this is not the best paid professional car makers in Stuttgart working for Mercedes. This is a bunch of very smart amateurs who have taken all the ingredients and put it together in a brilliant way."

Sunswift 7 should have been racing since the start of 2021, with events such as the prestigious World Solar Challenge on the schedule.

All that had to be shelved when Covid lockdowns severely delayed the build, and then also wiped out the majority of high-profile events as international teams were simply unable to travel.

But Prof. Hopkins, formerly Head of Operations for the Red Bull Racing Formula One team, was able to draw on his experience in the top levels of motorsport to guide the team through the challenges.

“That whole period of going in and out of Covid lockdowns reminded me very much of when I was in Formula One.

"In that high-pressure environment, when you are losing you can feel as if you are at rock bottom, but you know you have to retain your focus and work exactly the same as if you were winning," he says.

“You draw on a resilience you never knew you had. I think in that situation, it was just important for the Sunswift team to continue to communicate.

"If we weren't in a lockdown, we had to absolutely maximise the time we had because you never knew when something else was going to happen.”

For team manager, Mechanical Engineering student Andrea Holden, working on the Sunswift project from start to finish has been a massive thrill – albeit extremely demanding.

And she believes it is something every student should aspire to be involved with.

"I remember in the interview to join the Sunswift team, they said it would be the most challenging thing I could do. At the time I thought that was a bit dramatic, but it is absolutely correct,” Ms Holden says.

Sunswift 7 team manager Andrea Holden. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

"But as much as it is challenging, and also stressful, the benefits and the learnings from it outweigh that by 100 per cent.

"Meeting deadlines for university coursework is one thing – if you don't meet that deadline then the only person affected is yourself.

"But with a project like Sunswift, if you don't meet a deadline then it has a knock-on effect for many other people.

"I think that level of responsibility is a really good thing, though, and not many people experience it at university level.

"Some students might do internships and get real-world experience on projects for three months here or three months there.

"But we have been involved from the design phase, through to the build, then testing and hopefully achieving our goals.

"And I think that it's an absolutely invaluable experience."

Members of the UNSW Sydney student team who designed, built and developed the Sunswift 7 solar car. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

The result of the team’s effort is a car that weighs just 500kg, about one quarter that of a Tesla, and is so efficient that it will complete the 1000km world record attempt on just a single charge of its solar-powered battery.

That is the product of superb aerodynamics, with chief designer Ben Heina going back to the drawing board 57 times before he was happy with the car, as well as high performance in terms of converting energy from the solar cells to the battery, efficiency of the motors and throughout the drive chain, plus incredibly low rolling resistance.

All of which shows what is possible and what can be achieved, albeit with a significant weight advantage over road legal cars which require a host of safety features and also enjoy the benefits of an air conditioning system which Sunswift 7 has stripped out.

But Prof. Hopkins says: “We are using a standard battery and a standard solar panel, but we have focused on making it a super efficient car and shown what is possible.

“That efficiency means once we get up to 100km/h and take the foot off the accelerator I don’t think there is a straight stretch of road long enough, except for maybe somewhere in the Nullarbor, to measure how far it would keep going all on its own.

Sunswift 7 shows off its dihedral doors, inspired by those found on Koenigsegg luxury sports cars. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

“Very little rolling resistance and very little air resistance are what makes this car so efficient. And when you have an efficient car, you don't need a lot of battery to make the whole car work.”

But how does that translate into a regular production car that the general public might be able to purchase in the next few years?

“The technology is largely there to do it,” adds Prof. Hopkins. “Obviously, there are some practical things that would change it from being instantly transferable overnight. This is a prototype vehicle. We don't even have windscreen wipers, let alone air conditioning, let alone ABS or airbags or other safety devices.

“Technology has made production cars more efficient over time, but other things have equalised that and all those safety features which add more weight are a necessary part of that. Nevertheless, even with those safety features removed, we are showing what is possible.

“Personally, I don’t think there is anything to say that in 20 years, even 10 years, we couldn’t have a regular production electric car that weighs 500kg with full safety features included that can travel 1000km on a single charge.

“With the Guinness World Record, if we can prove that we can drive a car at reasonably high speed and do 1000km, it proves the technology exists. We just need to do some polishing with that technology to make it mainstream.

“Yes, there are probably some things required to enable such cars of the future to be built that haven’t even been created yet. That’s the advancement of technology.

“What we are really doing with Sunswift is a feasibility study. It’s an exercise to show what is possible.

“It's there to agitate and disrupt. We can show what is potentially achievable, maybe not with the ingredients that are widely available to everyone right now – but definitely showing what’s possible.”

And even UNSW alumna Robyn Denholm, who succeeded Elon Musk as chair of Tesla in 2018, has seen first-hand what is possible after she visited the Sunswift team – and told the undergraduates what an amazing job she thought they were doing.

As well as the Guinness World Record attempt, Sunswift 7 will push the boundaries of what is technically possible with regards to remote driving.

In association with team sponsor Optus, 5G receivers and cameras will be installed on the vehicle, allowing it to be driven by someone outside the car wearing a virtual headset.

And that someone will be none other than 2021 Bathurst 1000 winner Chaz Mostert who will pilot Sunswift around the famous Mount Panorama track in October.

With the benefit of more than 25 years of solar car development, the next big plan is for UNSW to launch the Sunswift Institute which will bring racing, technological innovation and automotive development all under one umbrella.

Prof. Hopkins believes that will continue to push the boundaries of what is possible for consumer electric vehicles of the future.

“The Sunswift Institute will stand for the advancement of technology in transport and ensure that we are innovators in that space. We want to be prepared to take risks because if we are attempting things that are safe, that’s boring.

“I think now is the time to really go out there and try to shift the needle, be ahead of the curve and do things that people haven’t done. It’s one thing to improve on what’s already been done, but let’s see if there are also completely different ways of doing things.

UNSW Professor of Practice Richard Hopkins talks with the Sunswift team during testing of the car at Sydney Motorsport Park. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

“We want to be known as innovators, but also to help build something here in Australia. We don’t want to teach great students just to have them get on a plane to work for prestigious companies in other countries.

“And I absolutely believe that motorsport and innovation work together to provide benefits to mainstream car buyers. You only have to look at Mercedes and the hybrid technology they have in their road cars which is a direct transition from their Formula One team.”