What is the latest advice on avoiding and treating monkeypox?

There are steps to avoid infection and a vaccine is likely, says a public health expert from the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney.

There are steps to avoid infection and a vaccine is likely, says a public health expert from the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney.

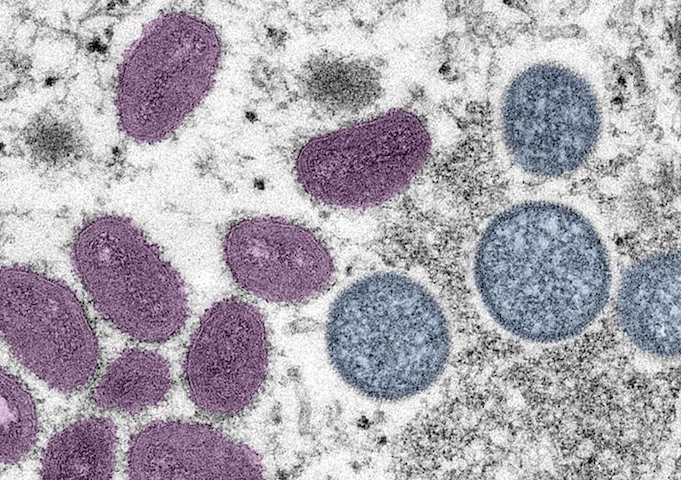

Monkeypox is a virus that was first discovered in Africa in 1958, but until recently widespread transmission has not been seen outside that continent. The virus is related to smallpox, but is far less likely to cause serious disease.

The sudden proliferation of monkeypox cases in nearly 80 countries, however, has caused the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’. This declaration is a global call to contain monkeypox – through identification, treatment and prevention – to prevent it becoming endemic.

As of 24 July, there were 44 confirmed or probable cases of monkeypox in Australia. This means that Australians should be alert and ready to respond thoughtfully to any increase in community transmission.

Australia's Chief Medical Officer has declared the increasing presence of monkeypox in the country a “communicable disease incident of national significance”.

The symptoms of monkeypox are similar to its more virulent cousin smallpox, but milder. They include fever, headache, swollen lymph nodes, chills, muscles aches and backache, and a rash that can look like pimples or blisters. This rash can appear on the face, inside the mouth, and on other parts of the body. In the current epidemic, the majority of people have lesions in the anogenital and oral areas.

Monkeypox is transmitted primarily through direct contact with infectious rash, scabs, pustules, and infectious bodily fluids, and through respiratory secretions and possibly droplets.

In essence, this means it is infectious through close physical contact. While it is not generally considered a “sexually transmissible infection”, ongoing investigations are evaluating its presence in and transmission by sexual fluids. Even if not classified as a STI, it is likely transmitted by the close contact that accompanies sex. It can also be transmitted through bed linen, clothing and towels that have been in contact with infectious secretions.

The vast majority of the cases of monkeypox outside Africa have been in populations of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), which raises the issues of potential stigma and discrimination. Lessons learned from HIV demonstrate that working in partnership with affected populations to address emerging infectious diseases is highly effective for developing acceptable, feasible approaches to prevention and care.

For example, in the early 1980s gay men in the US were advocating for condom-protected sex even before HIV had been identified as the cause of AIDS.

Conversely, stigma and discrimination are powerful barriers to disease prevention. If a disease is stigmatised, a person with symptoms may be less likely to seek medical care and to notify partners who may have been exposed. This stymies prevention initiatives.

Cooperation between affected communities and policymakers builds trust, allows for the sharing of information and the development of strategic approaches for prevention and to ensure that affected individuals and groups have access to treatment and care.

Currently Australia’s national HIV organisations and state -based LGBTQ organisations are collaborating with public health authorities and publishing up-to-date guidance on monkeypox prevention and treatment.

Access to a vaccine for monkeypox is likely. Photo: Unsplash

Specific vaccines for monkeypox have not been widely used, but vaccines developed for smallpox have some efficacy against monkeypox due to the similarity of the viruses.

Increased access to vaccines in Australia is likely, including those specifically developed for monkeypox. A smallpox vaccine is available, but given side effects particularly in immunocompromised people, including people with HIV, it is only recommended for high-risk contacts. In the very near future a specific monkeypox vaccine without these concerns should be available and would be used more broadly for populations at-risk, including GBMSM populations.

Preventive measures include avoiding skin contact and kissing, wearing masks and avoiding gatherings with people wearing little clothing (where skin contact might be hard to avoid).

The World Health Organization has also recommended people – particularly men who have sex with men – continue to learn about the virus, monitor themselves or others for symptoms, and to seek medical attention as needed.

People with the virus should isolate and follow health directives about accessing care (from an ethical perspective, such isolation should always be accompanied with reciprocal provision of care, support, and compensation for financial disadvantage).

Read more: Monkeypox in Australia: what is it and how can we prevent the spread?

Health system preparedness is needed to ensure that clinicians know when to test, to ensure that cases are identified swiftly so that appropriate treatment and prevention interventions can be deployed.

Once there is sufficient supply of the specific monkeypox vaccine, bio-behavioural approaches like ‘ring’ vaccination – vaccinating all known contacts of a case – may be effective in stopping transmission. Vaccination of GBM with multiple partners is occurring in North America and Europe and will be required in Australia.

For people with severe disease, or those with monkeypox who might be at risk of severe disease, antivirals are available in Australia, although they are still experimental. The preferred antiviral agent is Tecovirimat, which is held in the National Medicine Stockpile.

People who have had recent vaccination for smallpox may have some immunity to monkeypox. People who received smallpox vaccination more than 10 years ago however may no longer have protection. This may be important to consider with ‘ring’ vaccination strategies.

Dr Bridget Haire is a senior research fellow at the Kirby Institute, and an Associate of the Australian Human Rights Institute, UNSW Sydney. She lectures in public health and medical ethics. Prior to academia, Bridget worked in HIV and sexual and reproductive health for more than 20 years as a journalist, editor, policy analyst and advocate.

This article was prepared with additional input from The Kirby Institute’s Professor Andrew Grulich, Scientia Professor Gregory Dore and Cherie Bennett.