Reclaiming language is key to Aboriginal cultural identity and wellbeing

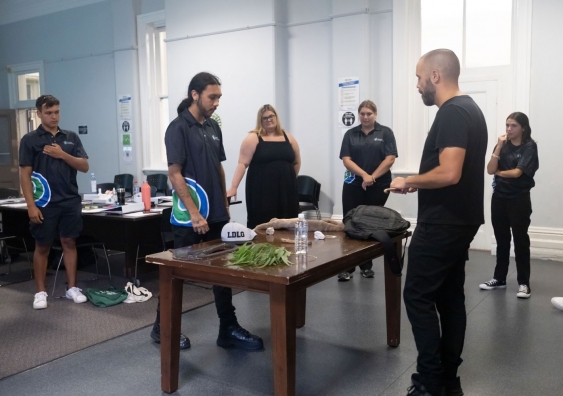

The Dharawal language is being learnt by younger generations thanks to a partnership between UNSW and the La Perouse Aboriginal community.

The Dharawal language is being learnt by younger generations thanks to a partnership between UNSW and the La Perouse Aboriginal community.

A new UNSW Sydney community partnership will support the revitalisation of the Dharawal language within the La Perouse Aboriginal community.

The partnership between the Gujaga Foundation and UNSW will use archival resources to describe the language and undertake language projects in collaboration with Dharawal language knowledge holders and Dharawal Elders. It will help widen use of the Aboriginal language across Dharawal Country and support the community’s rich cultural heritage.

The Gujaga Foundation (Gujaga) is the peak organisation for language, cultural and research activities within the La Perouse Aboriginal community. It works with Elders, senior knowledge holders and academics to foster a strong community identity.

Revitalising language, with its connections to country, spirituality and kinship, is integral to improving Aboriginal wellbeing, says Mr Ray Ingrey, Chairperson of the Gujaga Foundation.

“Spirituality is at the core of who we are on so many levels. It really connects us to all things within our country. And language for us facilitates that connection.”

Mr Ingrey will be working with Dr Clair Hill, a linguist from UNSW Arts, Design & Architecture who specialises in Australian languages, and Associate Professor Kevin Lowe, a Gubbi Gubbi man and expert in Aboriginal language policy and school curriculum implementation.

Dr Hill researches the interaction between language, cognition and culture, and collaborates with communities to translate this research into practical language documentation and language revitalisation products.

“When you hear people talk about the grief of that loss of language … and then you work on the languages and discover how much of the semantics – the meanings of the words and other interactional aspects – express important cultural views and cultural knowledge … the cultural value in revitalising these languages is self-evident. It's not only essential to these communities, but also for the whole of Australia,” she says.

Also, building capacity around language increases self-worth and strengthens cultural identity in Aboriginal communities, A/Prof. Lowe says.

“Our research in education has clearly identified that when Aboriginal kids have access to quality language and cultural programs, it really resonates with kids’ sense of identity and belonging in schools and their communities,” the UNSW Scientia Indigenous Fellow says. This has long-term benefits at an individual and a community level, he says.

Dharawal country stretches from Sydney Harbour to Shoalhaven, with the La Perouse Aboriginal community established as a permanent Aboriginal settlement in 1883 through the actions of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board.

Aboriginal people from the coastal areas adjacent to Sydney were forcibly housed on the mission as part of state government policies across Australia. Communities were heavily policed, with Aboriginal people prohibited from practising language and culture.

Today, the community still has families with ancient and unbroken roots to coastal Sydney. Revitalising Dharawal language means this cultural knowledge is captured for future generations, Mr Ingrey says.

The partnership will identify the best practices for language learning in revitalisation contexts. It will build on the strengths of Gujaga’s existing language program for adults and children.

Gujaga has run a semi-immersion language program through the Gujaga Early Childhood Learning Centre for almost 20 years and the Dharawal language is embedded in the centre’s daily activities.

Mr Ray Ingrey, Chairperson of the Gujaga Foundation. Photo: Rob Hookey.

“We have Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal kids access our service,” Mr Ingrey says. “So the Aboriginal kids are learning about their own cultural belonging in the world that we live in, and the other kids, they're getting a unique insight into the world’s oldest living culture.”

The project will evaluate the children’s language levels when they leave the centre and examine how best to retain this early language learning. It will conduct focus groups to identify meaningful outcomes for the local community.

The team will gauge community interest in partnering with local primary and high schools to explore the value of a language program that follows children from early childhood learning to achieve fluency by primary school end. This would allow career development to take priority in the later school years, Mr Ingrey says.

Read more: Closing the other gap: instilling Indigenous knowledge in young hearts and minds

The partnership will also support opportunities for later-year linguistic students to undertake collaborative research projects with the community. Students will lend their linguistic expertise to the language program, under the direction of Mr Ingrey and supervised by Dr Hill, analysing recordings, performing literature reviews and developing language resources that can be fed back into the community.

“It's going to be wonderful, hands-on work experience working with a community organisation, and putting the skills that they've developed through their degree into action and understanding the real-world issues in running a community-based language program,” Dr Hill says. “The move from the cerebral to the real space – it’s a powerful moment to build that into someone's degree experience.”

The community recognises having this ongoing linguistic support is important for the continued reclamation of Dharawal language, Mr Ingrey says. “[Also] some of our young ones are getting involved in [language] training and starting to ask how they can become linguists and so we … wanted to create those pathways with UNSW.”

Aboriginal languages are rich in linguistic diversity, increasing the value but also the challenge of maintaining them, Dr Hill says. While New Zealand has one heritage language, Australia has 28 distinct language families and at least 250 distinct language nations. Finding the resources required to service this is a challenge, she says.

“Ninety-four per cent of Europe is made up of one language family, so Australia has 28 times more linguistic diversity than the whole of Europe,” Dr Hill says. Also, there's a lot of new linguistic diversity emerging in creoles and contact languages – languages that mix English with local heritage languages, she says.

“Some First Nations kids come to school speaking an Indigenous language. Then they have an English-as-a-second-language learning experience, where they don't speak standard Australian English – they’ve had limited access [to it] and then they’re having their schooling in it and they're learning it at the same time,” she says.

“That has repercussions for that child's education experience and flow-on effects to employment, engaging with the world … all the things that we want for everyone in Australia.

Revitalising Aboriginal languages is key to Aboriginal cultural identity and wellbeing. Photo: Rob Hookey.

“We need to better understand the local language expertise kids bring into the classroom and how kids acquire languages in different ways for different uses, like formal education or community language revitalisation.”

By supporting communities to develop language materials and resources, research can facilitate community benefits beyond just the revitalisation of language, says A/Prof. Lowe.

“If a kid comes out of a language program, fluent in – as best as can be – language, it has multiple effects,” he says. “On the student in the immediate short term – in their engagement with school – but also in the longer term and building resilience within the whole community.”

This partnership is about investing in real-world change for the long term, says A/Prof. Lowe. “[It aims] to improve the capacities of communities to push back and to carve out a space for themselves based around, not just the aspiration for language and culture, but its actualisation,” he says.

Gujaga is committed to developing strong networks to benefit the community into the future, Mr Ingrey says. “Our challenge is to grow and continue to support our families. As old Gumbayngirr Elder Uncle Ken Walker would say, ‘It’s a long road to hope’. … It’s a long journey but it’s satisfying to hear Dharawal being spoken in our community, to hear kids singing children’s songs in language and greeting one another in language.”

Read more: Aboriginal language could help solve complex AI problems