Bring Them Home, Keep Them Home: reunifying Aboriginal families

An Aboriginal-led research project is developing greater understanding of the complex challenges Aboriginal families face reunifying with children removed to out-of-home care.

An Aboriginal-led research project is developing greater understanding of the complex challenges Aboriginal families face reunifying with children removed to out-of-home care.

Improving strategies for reunifying Aboriginal families is integral to reducing the over-representation of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care, says UNSW’s Dr BJ Newton. Dr Newton is leading a project to address the evidence gap in the lived experiences, successful pathways, and the scale and patterns of Aboriginal child removals and restorations at a population level.

The project, Bring Them Home, Keep Them Home, is the first Aboriginal-led research into the reunification of Aboriginal families worldwide. It will consider all Aboriginal children born in NSW since 2004. The research will enable greater knowledge and empowerment for Aboriginal people navigating the child protection system.

Bring Them Home, Keep Them Home supports the paradigm shift – from separating to sustaining Aboriginal families – needed to affect real-world change, says Dr Newton, a Wiradjuri woman and Scientia Senior Research Fellow at UNSW Arts, Design & Architecture.

“In Australia, Aboriginal children are 10 times more likely to be removed than other children,” she says. “With national reports estimating just 15 per cent of Aboriginal children in care likely to return home, such low rates are unacceptable given the priority outcome for children following removal is restoration to parents.”

The four-year project is a partnership between UNSW’s Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC), AbSec – the NSW Child, Family and Community Peak Aboriginal Corporation, Waminda – the South Coast Women’s Health and Welfare Corporation, South Coast Medical Services Aboriginal Corporation (SCMSAC), Illawarra Aboriginal Corporation and the University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

The project is funded by an ARC Discovery Indigenous grant and the interdisciplinary research team includes Associate Professor Kyllie Cripps (UNSW Law & Justice), Dr Kathleen Falster (UNSW Medicine & Health), Professor Ilan Katz (UNSW SPRC), and Associate Professor Paul Gray (UTS).

Read more: UNSW Arts & Social Sciences researchers receive ARC Discovery Indigenous grants

The project will produce a practical roadmap for Aboriginal parents whose children have been removed as well as accessible resources to help families, communities and caseworkers support and navigate sustainable restoration.

Insights obtained through rich interviews with Aboriginal parents and key stakeholders, along with Aboriginal-led community forums, will build sector understandings of the complex systemic challenges and facilitators to successful Aboriginal family reunification.

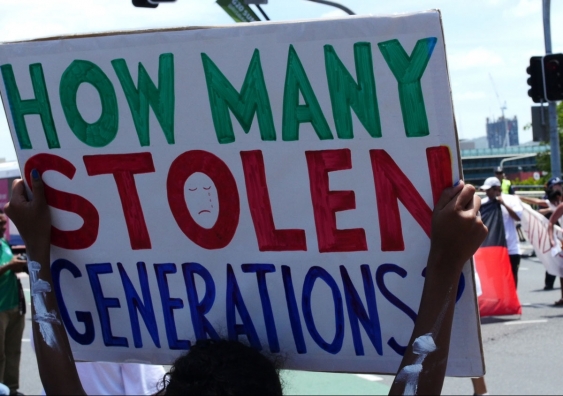

Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children make up 42 per cent of the total children in out-of-home care (OOHC), despite representing just 3.3 per cent of the Australian population.

Children growing up in OOHC are more likely to experience depression and suicidal ideation, suffer an interrupted education, and come into contact with the criminal justice system, Dr Newton says. “For Aboriginal children, it also disrupts their connection to kin, culture and land, which is essential to their sense of identity, health and wellbeing.”

The Closing the Gap report aims to reduce the rate of over-representation by 45 per cent by 2031. However, while family restoration is identified as the preferred pathway, in practice supporting families to achieve this is still in its infancy, Dr Newton says.

“Working with birth families, developing restoration programs, even family finding [locating Aboriginal family to support the family and care for the child, if necessary] – all that is a relatively new way of doing family casework. The research asks how we create an environment where reunification is prioritised.”

The relationship between Aboriginal communities and the child protection system is complicated by the legacy of colonial paternalism, she says. “Concerns around Aboriginal children can be exacerbated by systemic racism rooted in assimilation policies that promoted the erasure of Aboriginal culture. Being Aboriginal and living in poverty is historically [seen to be] synonymous, and living in poverty and being neglected has also been seen to be synonymous.”

In Australia, Aboriginal children are 10 times more likely to be removed than other children. Photo: Shutterstock.

Additionally, what constitutes ‘neglect’ is very subjective, she says. For example, when a child witnesses domestic and family violence (DFV), this can be considered neglect despite parents – most usually mothers – also being victims themselves. DFV also often impacts housing stability, another criterion for reunifying with your children.

Carers can also impede reunification, prioritising instead personal attachments to removed children, she says. For example, in a case where a primary-school-aged child in OOHC and her family were working towards reunifying, her foster family moved her five hours away without consultation, causing family visits to break down.

Social services and court processes can also be inaccessible, with some families denied the opportunity to appear in court: “They’re not empowered to make their own argument,” Dr Newton says.

“When your child is removed, the expectation is that the parents are going to pick themselves straight back up and march into court and be able to advocate for themselves. But the fact is, they're grieving,” Dr Newton says.

With no overarching restoration strategy, the sector is subject to inconsistencies in approach, under-resourcing and disparate levels of skill and experience. Support services needed at the prevention stage are often not initiated until a crisis is reached, she says.

Reunification programs typically operate on a deficit model, placing blame with the parents; “but we know many children are removed for unjust reasons,” she says. Additionally, timeframes do not allow for contingencies, such as waitlists for housing, drug and alcohol treatment, even the grieving process and potential shame of having your children removed.

“When your child is removed, the expectation is that the parents are going to pick themselves straight back up and march into court and be able to advocate for themselves. But the fact is, they're grieving,” Dr Newton says. “So, how do you get back your kids? The cycle of oppression just makes it that much harder for families to be able to move forward.”

Dr Newton specialises in participatory and community-based methods to develop the knowledge and evidence base of Aboriginal people from their perspective.

“My passion is to amplify the voices of Aboriginal peoples and communities so that their world views and experiences are heard, respected and are catalysts for change,” she says.

The project is guided by an Aboriginal advisory panel and consists of a series of community forums led by Aboriginal organisations, to ensure Aboriginal community needs, priorities and cultural protocols are met. The project’s Aboriginal partners led the initial forum in March, exploring what restoration from out-of-home care looks like for Aboriginal families, communities and services in the Illawarra Shoalhaven area.

Participants reflected on the typical, most challenging and ideal scenarios of child removal and family restoration and identified key factors impacting these pathways. A lack of fair opportunity for parents to achieve restoration was acknowledged as well as the need for greater support for families and children prior to removal (through early preservation work), while children are in care and post-reunification.

“The aim of the forum was not to ‘educate’ non-Aboriginal participants, but to cultivate an open discussion and gather a collective voice across the sector to prioritise restoration,” says John Leha, Chief Executive Officer from AbSec. “Restoration is both an outcome and a process that begins with early preservation work and ends with our children ‘going home’.”

The cycle of oppression just makes it that much harder for families to be able to move forward, says Dr BJ Newton. Photo: Dr BJ Newton

The project will also hold practitioner forums state-wide to understand restoration across the different geographic and demographic contexts. Fostering a community of practice will support these new legacies of collaboration beyond the life of the project.

Working with Aboriginal organisations Waminda and AbSec ensures the research translates into real-world needs, Dr Newton says. The project is working on a Know Your Rights resource for women whose children have been removed with Waminda and a policy document for practitioners and policy workers working with Aboriginal communities with AbSec.

“Research collaborations that bridge the gap between Aboriginal communities and services and the child protection system are fundamental to achieving sustainable family restoration,” a statement from Waminda says. “Creating strategies that recognise and support Aboriginal kinship models, strategies that actively engage with Aboriginal families, that give them a voice, offer the best opportunity for reunification and prioritise the ongoing welfare of our children.”

The research has personal resonance for Dr Newton whose grandfather was removed at 11 years old.

“He talks about two men in black suits rolling up to where he was living. His mum and his cousin trying to stop it... They took him, and they took his baby brother, and his sister hid under the bed, and then, to protect her, they ended up sending her to live with white family members. It was awful.”

It’s time to end the cycle of separating Aboriginal children from family, culture and Country, Dr Newton says. By identifying and showcasing successful pathways to restoration, the research will empower Aboriginal peoples to sustain their communities.

“This research will be key in generating knowledge for how to bring our children home and keep them home.”

Read more: Reunifying First Nations families: the only way to reduce children in out-of-home care