'Be alert, avoid complacency,' crowd safety expert says ahead of busy festive period

UNSW Sydney academic Dr Milad Haghani says it’s not impossible for a deadly crush like the one in South Korea to happen in Australia.

UNSW Sydney academic Dr Milad Haghani says it’s not impossible for a deadly crush like the one in South Korea to happen in Australia.

An expert in crowd safety has urged Australians to be vigilant when out celebrating during the busy Christmas and New Year period in the wake of the deadly crush in South Korea.

Dr Milad Haghani from UNSW’s School of Civil & Environmental Engineering has extensively researched the way groups of people interact in large crowds.

And he says the best way for revellers to stay safe in places where large numbers are gathering in confined spaces, such as at specific events or transport hubs, is to be alert to danger and to try to recognise when a crush situation may be imminent.

More than 150 people died, and another 200 were injured, in a crowd crush in October when hundreds of thousands of people were celebrating Halloween in one of Seoul's most popular nightlife districts.

Dr Haghani has warned that although a such a major disaster has never previously happened on Australian soil, that does not mean it’s impossible.

Indeed, just last week there was a crowd incident at a Steve Lacy concert at the John Cain Arena in Melbourne which did not result in any injuries but did spark an internal review by Melbourne and Olympic Parks which manages the venue.

“Knowing what happened in South Korea, and knowing what has happened in events similar to that in many different countries around the world, there is no reason for people not to think that there could be a similar incident here in Australia.

“We also need to learn from near misses that have happened in Australia, including the incident at the Steve Lacy concert. If we don’t learn from near misses, then we will have to learn from real catastrophes and this is an outcome that everyone should try to avoid,” Dr Haghani says.

“It is good not to have a feeling of complacency – that this is Sydney, or Melbourne, so it’s not an issue.

“Unfortunately, my research has shown that these crush events have been increasing in frequency globally over the past two decades. They are particularly happening more often around the world since COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted.

“And while it is true that Australia generally has a good record – even though we have a lot of big events where large crowds gather – we cannot be complacent. Just because there were no deaths or injuries it does not necessarily mean an event was 100 per cent successful. In fact, we have had several near misses before, and it was only fortunate that those did not result in any loss of life.

“In South Korea, the Halloween festival had been going on for two days previously and the deadly crush happened on the third night. There may well have been two near-misses the first two nights that were ignored, so it’s wrong to think that just because there have not been serious incidents before at a certain event that they could not happen in future.

“Unfortunately, we can see that globally we are not even learning from the incidents where sadly there were deaths and severe injuries.”

Dr Haghani says that while people should expect to be able to go to big events and enjoy them safely, they can also be mindful of their environment to avoid being caught in the most dangerous situations.

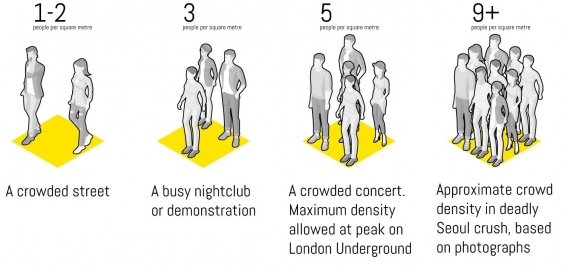

Being alert could be crucial, since research shows that once the crowd density rises above about seven people per square metre in a large crowd, there may be very little that any individual can do to protect themselves.

Understanding crowd density can be important for people to recognise when dangerous crush situations are close to developing. Illustration courtesy of Straits Times

“Everybody thinks when there is a big event going on, like a concert or New Year’s fireworks, that crowd safety is purely down to the authority managing the event,” Dr Haghani says.

“But I also think the people attending need to be prepared and that is something that often gets forgotten. The two things should go hand in hand.

“As a researcher, I can say that the overwhelming conclusion from analysing previous disasters is that predominantly the cause is nothing but excessive density.

“If a crowd in a certain area is very large, as in thousands of people, and the density is more than seven or eight people per square metre then it creates a phenomenon known as ‘crowd turbulence’.

“Essentially, at that point the crowd as a whole acts like a fluid and the individual people in the crowd are not in control of how they move or what actions they can take. Unfortunately, there is very little a person can do once they are in that situation.

“The only thing an individual person can do in that circumstance is to have some sort of awareness about crowd density, and a perception of what is a dangerous density level.

“If people are aware of that concept, then they can try to read the signals early.

“One signal may be that there weren’t really any restrictions on people entering a specific area, or they can’t easily see an exit route. Those might be red flags.

“If they can read those danger signals early, then they can try to react while they are still able to move around and navigate themselves through the crowd to a safer place.

“Because if the situation continues to worsen, there may be a point where they cannot move by their own choice and then it is too late.

“Once you get to a crowd density level that feels uncomfortable, and which indicates there might be a level of danger, then it’s already quite hard to navigate out of that situation.

“This is why prevention of these type of incidents falls mainly on the authority who is in charge of crowd control and crowd management. It is their responsibility to ensure people are safe and that no single person should be having to make that life-or-death decision about escaping from a dangerous crush.

“A key factor is to recognise that ‘crowd security’ is not necessarily the same as ‘crowd safety’. While police presence is essential in providing security, that does not necessarily guarantee that crowd crushes do not happen.

“Prevention of such incidents requires specific considerations and management mechanisms to be put in place prior and during the event, and that goes beyond sheer presence of police and authorities. Pre-planning, scenario testing and active monitoring and management are the key in these circumstances.”

Although keen to increase awareness of the potential dangers of large crowds, Dr Haghani is dismayed at the advice he has seen given by some non-experts to anyone unfortunate enough to be caught in a crush situation.

One video from ABC News in America, which has been shared nearly 14 million times on social media, suggests that taking up a boxing stance can prevent people being pushed forward in a large crowd.

Many media reports of incidents also use the words ‘stampede’ or ‘mass panic’.

Crowd safety is also paramount at transport hubs after big events where large crowds can gather in confined spaces. Photo from Shutterstock

“In many cases none of that is correct,” Dr Haghani says. “Nobody is misbehaving, nobody is unruly and nobody is running around – because obviously in a crush there is no space to do so.

“Reporting such as that is unhelpful because it puts the blame on the people who were the victims.

“I have seen people react to that ABC News video and say ‘Oh, I wish I had seen that before, or told my friend and I might have helped to save their life’.

“But that specific video has a dense group of people in a very open space. They still have room to adapt their movement. In a deadly crush everyone is in a restrictive space and nobody has authority over their own body, let alone being able to widen their stance and put their hands up to brace.

“Again, it’s a form of victim blaming to suggest people should do that. People might feel guilty if they think they should have done that, but in reality that would be impossible and unfortunately there’s very often nothing you can do once the situation gets to that danger level.”

Overall, Dr Haghani says people should not be excessively apprehensive about attending events where large crowds are expected to gather.

“If there is good crowd management in place then going to a big event should pose no danger,” he says.

“We do have expertise and analytical capabilities and enough skilled people in the industry to ensure everything can be safe – so I hope there is no reason for the general public to be too alarmed.”