Dam safety: study indicates probable maximum flood events will significantly increase over next 80 years

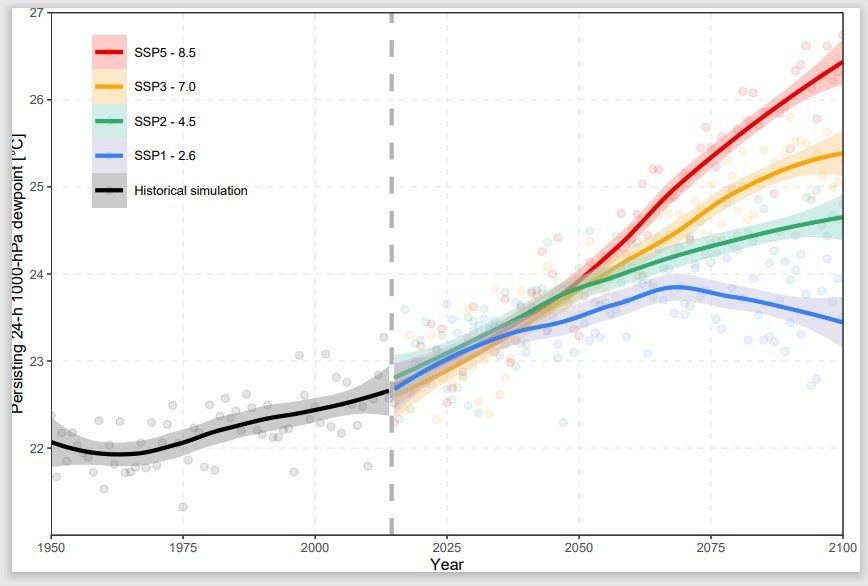

Industry-funded research says existing models for potential maximum rainfall are out of date and suggests existing dams are at greater risk due to spillway inadequacy.