Kirsty has given birth to a baby boy. A year ago, she didn’t have a uterus

This is the first baby born in Australia via uterus transplant, part of a clinical trial led by researchers from UNSW Sydney and The Royal Hospital for Women.

This is the first baby born in Australia via uterus transplant, part of a clinical trial led by researchers from UNSW Sydney and The Royal Hospital for Women.

Australian first, medical breakthrough, media sensation – there are many ways to describe the birth of baby Henry at The Royal on 15 December. To mother Kirsty Bryant, Henry’s arrival means a new member of the family, just in time for Christmas.

“I'm so excited. I never thought this would happen... Dreams are coming true,” Kirsty says.

Henry’s birth is a significant moment in Australian medical history, changing the future of infertility treatment. After decades of research to establish the uterus transplantation procedure in Sweden and bring it to Australia, women without a functioning uterus could hope to carry a baby.

Just 12 months ago, pregnancy was out of the question for the 31-year-old from Coffs Harbour. In 2021, after giving birth to her first daughter Violet, Kirsty suffered a life-threatening bleed and needed an emergency hysterectomy. She was told that she would never carry another child.

“I’d grown up with such a good friend in my brother. If something went wrong, we could lean on each other… Because of that love of having a sibling, I knew that when I had children myself, I wanted more than one,” Kirsty says.

“As soon as I was in recovery, we were discussing options like adoption and surrogacy… But I just knew that I wanted to be pregnant. I wanted to carry the baby.”

Kirsty then came across a clinical trial in Sydney for uterus transplantation, a new procedure that had never been performed in Australia. The trial is led by Associate Professor Rebecca Deans, clinical academic at School of Clinical Medicine and gynaecology specialist at The Royal and Sydney Children’s Hospital. Funded by The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation, the trial is held at The Royal, Prince of Wales Hospital and Westmead Hospital.

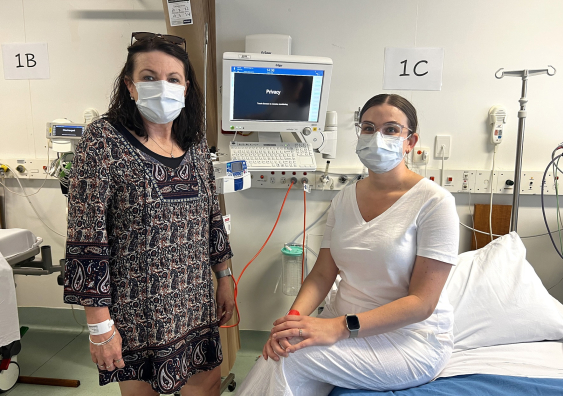

Michelle Hayton and Kirsty Bryant before their uterus transplant surgery at The Royal. Photo: South Eastern Sydney Local Health District.

Right away, Kirsty’s mother Michelle Hayton offered to give her uterus to her daughter, and the pair enrolled in the clinical trial. Michelle didn’t need more than a moment to think about it – she just wanted to help Kirsty fulfill her heart’s desire of growing her family.

In January 2023, after a painstakingly executed 16-hour dual surgery, Kirsty became the first person in Australia to receive a uterus transplant. At this point, fewer than 100 transplants had been performed worldwide. By May, Kirsty was pregnant, carrying a baby in the same uterus that she was grown in.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d be the first transplant patient,” Kirsty says.

“I’m so grateful that I found this trial and was accepted and have been able to go on this journey… And then who would have thought that by having a uterus transplant in January, I’d have another member of the family by Christmas?”

A/Prof. Deans did not imagine that she would make medical history as the lead surgeon of Australia’s first uterus transplant. When researchers in Sweden were pioneering the procedure in the 2000s, A/Prof. Deans was uncertain about the ethics of patients undergoing a complex, risky surgery that is not lifesaving.

Spending time with her patients as a specialist in paediatric and adolescent gynaecology, A/Prof. Deans started to change her mind. Many of her patients were young women born without a functioning uterus who would never have the opportunity to carry a pregnancy.

“Then I saw patients born without a uterus who were desperate… I saw patients go through surrogacy, and that’s a really hard journey. In Australia, it is illegal to pay a surrogate, so it must be altruistic. People are forced to go overseas for surrogacy and there are issues around that too – it’s an ethical minefield,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“Some of the women I was seeing clinically would say to me, ‘why can’t you do uterus transplantation?’… Eventually I got really on board with the idea of uterus transplants and became passionate about it.”

Associate Professor Rebecca Deans and Professor Jason Abbott are gynaecology specialists and researchers. Photos: Supplied.

A/Prof. Deans was met with scepticism from many of her colleagues when she started working to establish an Australian uterus transplants clinical trial.

“Rebecca was my PhD student at the time. She came to me and said that she wanted to do some work with uterus transplantation. And I thought: that’s going to be super complex…” says Professor Jason Abbott, who is a gynaecologist and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at UNSW Medicine & Health.

Prof. Abbott has dedicated his career to improving outcomes for patients with endometriosis, a condition in which tissue similar to the uterus lining grows in other parts of the body, causing chronic pain and sometimes infertility. He spends much of his time taking uteruses out to treat endometriosis, and definitely not putting them in.

“I was a bit of a non-believer at the time. But Rebecca being who she is, and really wanting to do this, she gave me some really good reasons about why it was important,” Prof. Abbott says.

It took a decade for A/Prof. Deans and her team to establish the uterine transplant clinical trial in Australia, navigating complex ethics approvals and the COVID-19 pandemic. They also needed to study patients’ perceptions of the procedure and the potential psychological impacts. The researchers collaborated closely with Professor Mats Brännström from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, who was the first in the world to successfully perform the procedure.

“I had to move heaven and earth… But when the first transplant was successful, it was so good,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“You have those moments in your life: the day you get engaged, get married, have your babies. I put it up there on that level.”

The preparation for uterus transplantation begins long before the day of the surgery. First, the recipient must undergo the first stages of vitro fertilisation (IVF) and freeze at least five embryos.

The recipient also needs to find a donor with a matching blood group and human leukocyte antigens (HLA), to reduce the risk of donor organ rejection. Like Kirsty’s mum Michelle, most donors for uterus transplants so far have been living relatives. However, the clinical trial also accepts altruistic unknown donors and deceased donors.

On the day of the transplant, the recipient and donor have surgery in parallel theatres. First, the donor’s uterus is removed, along with the surrounding blood vessels – a marathon surgery that can take up to 12 hours. Next, the uterus and blood vessels are transplanted into the recipient, which can take up to eight hours.

“The patient has got to want to carry a baby badly, because it’s such a difficult, complex surgery,” Prof. Abbott says.

“We’re talking about one of the most complicated surgeries that we have ever seen in pelvic medicine.”

The post-operative recovery period is critical for both the donor and the recipient. For the donor, clinicians carefully monitor the health of their bladder and ureters, which are at risk of being injured during the surgery.

Following the surgery, the recipient takes immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection of the transplanted uterus. These medications are then gradually reduced to a level safe for pregnancy and the recipient undergoes an embryo transfer, with one frozen embryo inserted into the newly transplanted uterus.

Once pregnant, the recipient receives routine antenatal care along with specialised monitoring by a high-risk obstetrician and the clinical transplant team.

At approximately 37 weeks, the baby is delivered via Caesarean. There are different reasons for this: the pregnancy is considered high risk, the recipient may not be able to feel contractions or movements in the uterus, and some women born without a uterus may be unable to deliver a baby vaginally.

“The uterus can remain in place for two births or up to five years after the transplant,” A/Prof. Deans says.

According to A/Prof. Deans, it’s important to limit the amount of time that the recipient is taking immunosuppressive drugs, as they make recipients vulnerable to infection and other side effects. Therefore, it’s not a lifelong transplant.

Another thing that complicates uterus transplantation is the fact that every recipient is unique.

“There could be variations in their anatomy that must be taken into account during surgery, and it’s not possible to predict how they will adjust to the transplanted uterus. No two patients and their experiences are the same,” A/Prof. Deans says.

Prue Craven found out that she was born without a uterus at the age of 16.

“I still hadn’t gotten my period… The GP had no clue what it could be,” Prue says, now 37.

“So I had ultrasounds done. They were calling more and more specialists into the room to look at the ultrasound – at that point, what I had was not something that many people were familiar with… It was so intimidating.”

Prue was told that she has Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) Syndrome, a condition that approximately one in 4500 females are born with. MRKH Syndrome mainly affects the female reproductive system, meaning that while the ovaries function normally, the uterus is underdeveloped or absent.

“In that moment, I couldn’t quite understand the gravity of what that would mean. I knew that I couldn’t carry a baby, but I just didn’t know how much it would impact me emotionally and psychologically,” Prue says.

Prue had always wanted to be a mother, looking after her three younger siblings when they were growing up together in Melbourne. After marrying Tom Craven, who she’d known since they were toddlers in playgroup, and training as a paediatric nurse, Prue embarked on her fertility journey.

Prue and Tom Craven have been trying to start their family for over a decade. Photo: UNSW Sydney / Richard Freeman.

For 11 years, the couple tried every possible avenue and spent more than $120,000. Prue and Tom attempted surrogacy multiple times overseas and in Australia, working with four potential surrogates, with over six embryo transfers and two miscarriages. This required many cycles of IVF, with Prue ending up in hospital due to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. The couple also tried adoption, but would be ineligible if they had embryos in storage, and the average wait time for a child would be 7-10 years.

“We felt really isolated in that whole process. And then to throw all of our money that we made and our hearts and souls into it, for it all to fail,” Prue says.

“Looking back, I honestly do not know how we got through it.”

When Prue first heard of uterus transplantation, she was immediately interested. After Prue’s mother Julie was not a blood type match, Julie’s friend Madonna Corstorphan offered to donate her uterus.

“My mum’s friend Maddie just said: ‘I’ll do it.’ Easy as that… I was quite taken aback actually, that she wanted to do something like this,” Prue says.

“Then I met A/Prof. Deans. She has this persona about her that she is genuinely passionate about what she’s doing, and really invested in the process.”

In March this year, Prue became the second patient in A/Prof. Deans’ trial to receive a uterus transplant – but her fertility challenges didn’t just disappear with the transplant.

“I always believed that if I was going to share my transplant journey, I was going to be real about it. I’m not doing anyone any favours by sharing this glossy version of the process,” Prue says.

Because her donor isn’t a genetic match, Prue has been taking higher doses of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection of the uterus, which have multiple side effects. There was also risk of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection from the transplanted uterus, requiring Prue’s embryo transfer to be delayed.

“We’re talking about baby names and talking about being parents… But it’s really hard to be hopeful in this process,” Prue says.

“We just had to keep pushing on and keep waiting.”

The ethics of uterus transplantation are undeniably complex, with the procedure carrying risks for both the donor and the recipient, and no guarantee of pregnancy. The science behind uterus transplantation is also complex, with the researchers developing new insights as the trial progresses.

“Firstly, we’re definitely increasing our understanding and knowledge of gynaecology… Having thought that I knew a lot about the female pelvis and female anatomy and female physiology, it’s really clear that this program has expanded that,” Prof. Abbott says.

For example, the uterus transplantation clinical trial is shedding light on pelvic pain, a common but poorly understood problem for women.

“Both of the recipients have described some element of menstrual pain and pelvic pain… But the nerves to the uterus are not attached,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“That suggests that where the pain comes from is the pelvis rather than the uterus. I think that’s a really fascinating thing to look into.”

Associate Professor Rebecca Deans (left) established the uterus transplant clinical trial across The Royal Hospital for Women, Westmead Hospital and Prince of Wales Hospital. Photo: The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation.

There are also new learnings about the side effects of organ transplantation and immunosuppression drugs, which are an everyday reality for thousands of Australians.

“You don’t usually get an opportunity to work out whether side effects have occurred as a result of the transplant or the immunosuppression drugs, or if they’re reversible… It’s fascinating that this is an organ that will be removed – it’s only in for up to five years,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“When we take out the uterus, we can monitor if the side effects are ongoing.”

Due to the complexity of uterus transplantation, clinicians have had to engage in unprecedented levels of teamwork, A/Prof. Deans says. These learnings are important, as our health system becomes more collaborative and multi-disciplinary to care for patients with complex diseases.

“This isn’t about one surgeon or one team… We’ve gained new insights around the collaboration and the team building and the ability to get this going across different hospitals,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“That’s given me hope. Often it seems like this sort of collaboration is just too hard to achieve.”

As the clinical trial continues, the researchers are mapping a path for uterus transplantation to become accessible to more Australians. They need to provide evidence that the procedure is acceptably safe and delivers significant benefits to patients.

“Hopefully one day women who have been born without a uterus are able to access this through clinical medicine and through the public health system in Australia,” A/Prof. Deans says.

“It just shows what modern medicine can do. It can overcome a lot of these barriers.”

In September, six months after receiving her uterus transplant, Prue underwent her first embryo transfer. Then, after over a decade of trying to start her family through surrogacy and adoption, she was pregnant.

“Considering how long the journey has been up to this point, it’s just so surreal. It’s like we’re living a dream,” Prue says.

“It’s an incredibly special time. But with a lot of anxiety and fear, obviously, about the impact of the transplant on being pregnant. There are lots of unknowns, which have continued to unfold over time.”

Prue Craven fell pregnant after her first embryo transfer. Photo: Supplied.

Like some people living with organ transplants, Prue has developed diabetes, requiring daily insulin injections. She has also recently been experiencing anaemia due to the immunosuppressive drugs, which drains her energy and needs to be managed with additional medications.

Now in the second trimester, Prue and Tom are awaiting the arrival of a little girl.

“The next steps are about making sure that all the little issues I’ve got with the anaemia and diabetes are being managed as much as possible. And I’ll do whatever treatment is necessary to get through this without impacting my health too much and also impacting the baby,” Prue says.

Prue is excited about what her journey represents for other women with MRKH, who could have never previously hoped to become pregnant.

“We’ve made something that seems impossible, possible,” Prue says.

“I think that this is going to give a lot of hope to women like me.”

As Kirsty welcomes her son Henry, she reflects on the experience of receiving Australia’s first uterus transplant. The support of her family, her doctors, the clinical trial team and The Royal has been critical.

“It’s a wonderful gift. But it is a lot for a person to go through and you need lots and lots of support… It takes a village to make a baby this way!” Kirsty says.

“I never thought this was possible. After Violet’s birth, I threw out all my maternity clothes… Now I’m bringing another baby into the world!”

Kirsty is looking forward to getting to know Henry.

“Once I’m out of recovery, I can be with my baby and with my family and watch their reactions to meeting our new family member. I’m so excited.”

The uterus transplant clinical trial is being held at The Royal, Prince of Wales Hospital and Westmead Hospital. Women who are candidates for a uterus transplant include those born without a uterus, or those who’ve had their uterus surgically removed for reasons such as cancer or complications with childbirth. For more information about the trial, reach out to The Royal at contactus@royalwomen.org.au. To donate to the trial, visit The Royal Hospital for Women Foundation's website.