The Illuminators: Scope for Change 2025

Curators: Dr Krystyna Gieniec, Dr Valentina Rodriguez Paris, Dr Shirin Ansari

Exhibitors (in alphabetic order): Moqaddaseh Afzali Naniz, Saba Altaf, Shreya Elizabeth Boby, Dr Zuzana Coculova, Derya Dik, Dr Marija Dinevska, Xue Dong, Elise Elkington, Elise Georgiou, Dr Krystyna Gieniec, Upasana Gupta, Shannon Handley, Siti Humairah Harun, Aline Knab, Dr Fiona Knapman, Ella Lambert, Yu Lei, Qinyu Li, Dr Bo Lin, Ellie Mok, Lamia Nureen, Dr Lily Pearson, Dr Valentina Rodriguez Paris, Dr Sara Romanazzo, Dr Claire Sayers, Dr Giulia Silvani, Thai Hong Anh Tran, Dr Umme Laila Urmi

Scroll below to meet the Illuminators and click beneath their profiles to view their art.

Award recipients

Congratulations to the recipients of the winning submissions voted through during UNSW Diversity Festival 2025!

People's Choice Award: Favourite Image

Tagged at the Borderline

Elise Georgiou

The Illuminators Image Prize: Co-Second Place

A Silent Scream of Char

Yu Lei

The Illuminators Image Prize: First Place

The Great Escape

Dr Giulia Silvani

People's Choice Award: Favourite Video and The Illuminators Video Prize: First Place

Sensory Neurons Beyond the Brain

Dr Lily Pearson

The Illuminators Image Prize: Co-Second Place

Glowing Mozzies

Dr Claire Sayers

The Illuminators Video Prize: Second Place

Molecular Archery: A Crossbow-Shaped Cell in Action

Shreya Elizabeth Boby

Exhibitors

Moqaddaseh Afzali Naniz

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Engineering

m.afzali_naniz@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Leica

As part of my research, I tested if my engineered thin films, about the thickness of a human hair, were safe for cells. This is the first step toward future medical use. This image shows HeLa cells, which are widely used in labs to check material safety. The test ended after three days and showed the cells stayed healthy on the films, but I kept the samples a little longer out of curiosity and took this image on the seventh day. By then, the cells crowded together with no space to spread, some fading while others endured. A moment beyond the test.

Saba Altaf

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences

s.altaf@unsw.edu.au

Shreya Elizabeth Boby

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

s.boby@student.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss ELYRA

Cells in our body come in many shapes and sizes, and this can affect how molecules move inside them. We can control a cell's shape using micropatterning, and guiding it into a crossbow-like shape makes it easier to study molecule movement. In this movie, the glowing spots show transferrin, a protein that carries iron, moving through the patterned cell. This approach allows us to investigate how cells transport different molecules in a controlled manner.

Dr Zuzana Coculova

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW Faculty of Science

z.coculova@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Olympus IX73

A tiny musical instrument appeared as if by magic, growing right before my eyes. After the sample was left aside for a while, the mixture of different salts started to crystallize into a variety of shapes and sizes. Among them, this silent sub-millimetre harp seems ready to join a microscopic orchestra.

Derya Dik

PhD Student

Neuroscience Research Australia

z5392064@ad.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM800

Star-shaped cells called astrocytes (blue) extend their arms to wrap around blood vessels (image centre, circular layers of magenta + yellow) in the brain. This contact helps control what enters the brain, playing a quiet but crucial role in protecting and supporting neural function.

Dr Marija Dinevska

Early-Career Researcher

Garvan Institute of Medical Research

z.coculova@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Leica Stellaris-DIVE

Recorded for over an hour, this time-lapse movie shows lab-engineered immune cells called CAR T cells (red) systematically searching for and engaging with cancer cells (white). The dynamic behaviour demonstrates how CAR T-cell therapy works to locate and attack cancer cells specifically while sparing healthy tissue.

Xue Dong

PhD Student

UNSW School of Chemical Engineering

z5547462@ad.unsw.edu.au

Elise Elkington

PhD Student

UNSW School of Chemical Engineering

e.elkington@student.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: JEOL JEM-F200 S/TEM

This is a close-up view of silver catalyst particles, which are special materials that help speed up chemical reactions. Under the powerful beam of an electron microscope (which uses tiny, charged particles, called electrons, to see things far smaller than light can show!), the material unexpectedly “exploded”. Instead of scattering randomly, the silver particles perfectly reassembled themselves across the thin carbon film that holds the sample in place. Catalysts like these play a vital role in environmental technologies, helping clean our air, break down pollutants, or turn harmful gases into safer ones. Sometimes, even scientific accidents create something beautiful.

Elise Georgiou

Honours Student

UNSW School of Clinical Medicine

elise.georgiou@student.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM 980

Ubiquitin is a protein that serves to identify and 'tag' unwanted proteins in cells so that the proteins may be degraded. While investigating how mouse eggs matured within the laboratory to eliminate unwanted proteins, we have observed large ubiquitin clusters (shown as red dots) external to the egg, specifically in the zona pellucida! The zona pellucida is the thick, protective layer that surrounds the egg and is the first layer of the egg that the sperm cell will have to penetrate to initiate fertilisation. The zona pellucida is surrounded by supporting somatic cells called cumulus cells (shown in purple), and string-like structures called transzonal projections (shown in green) which work together to deliver nutrients to the egg. It remains a question as to whether ubiquitin is associated with these structures, or if it represents a novel interface right at the borderline!

Dr Krystyna Gieniec

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

k.gieniec@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Olympus VS200

When we look at breast tissue under the microscope and use stains to highlight particular structures, we see beautiful branching tree-like architecture embedded within fatty connective tissue. In the top image, we can appreciate that these trees (pink) are encased in a layer of collagen (blue). We can then use microscopy techniques to examine the types of collagen present (indicated by red or green colour) in the bottom image to further inform how the breast tissue is organised, and whether this organisation changes during times of increased breast cancer risk e.g., in the 10 years following childbirth.

Upasana Gupta

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

upasana.gupta@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Lucifer - TIRF (custom built)

I am working with a protein that makes tiny holes in our cells, causing the cells to swell up, which ultimately kills them. In this video we observe a type of pore-forming protein called gasdermin. In my lab, we are on an inquisitive journey to find out how fast this protein assembles into forming a hole. When a germ invades our cells, our cells get stressed out and try to kill the germ. This is when gasdermins come into action and start forming tiny pores in the cells. Specifically, the pores are formed in lipids, which are fat-like material that make up our cells.

While examining this protein, a fault in my salt solution resulted in the stretching of some of the nice, rounded bubbles made of lipids (red) into elongated strings. In green is the pore forming protein, gasdermin, attacking these lipids, making it appear as a heavy commute on a one-way street!

Shannon Handley

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Engineering

shannon.handley@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Olympus FV3000

These glowing monocytes, a type of large, specialised white blood cell that are the body's first responders to infection and inflammation, are lit up with dyes that highlight their internal structures including the nucleus, the control centre of the cell, and mitochondria, the powerhouse of the cell. By studying their colours and shapes under the microscope, we can learn how healthy the cells are and how well they’re functioning - like watching tiny defenders throw a light show to signal how well they’re working. Here we can see the nucleus (cyan), mitochondria (green) and reactive oxygen species (red) present in the cell.

Siti Humairah Harun

PhD Student

UNSW School of Chemical Engineering

s.harun@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Nova Nano SEM 450

This 2D silicon and oxygen-based layered nanomaterial (super tiny versions of material) is capturing attention for its promising potential in energy storage (battery or capacitor) due to their high surface area and semiconductive nature. A semiconductor is a material that partly conducts electricity — more than an insulator but less than a metal. The performance of a siloxene can be highly tailorable according to the desired application. This material typically appeared as stacked sheets (like stacked papers) at microscale, but here it shows an unusual shape resembling a mini love.

Aline Knab

PhD Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Engineering

a.knab@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Olympus IX83 confocal microscope upgraded to a multispectral system by Quantitative Pty Ltd

This work captures the natural glow of healthy skin cells (left) and two types of melanoma skin cancer cells (middle and right). What makes it remarkable is that no dyes or stains were used. This natural glow reflects the cells’ metabolism, giving us a unique window into their inner workings without disturbing them. Using advanced imaging techniques and machine learning, we can distinguish healthy cells from cancerous ones based solely on their emitted light. This gentle, non-invasive approach could help improve how we detect and study cancer cells in the future.

Dr Fiona Knapman

Early-Career Researcher

Neuroscience Research Australia / UNSW School of Biomedical Engineering

f.knapman@neura.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM 800

Gene therapy can give cells new instructions to make useful proteins. Here, it was used to make rat tongue muscles produce light-sensitive proteins: when exposed to light, they contract and open the airway. This approach could one day offer a new treatment for sleep apnoea, where current therapies often fall short.

Left image: Temporarily reducing the body’s natural immune defences allows the proteins to be expressed strongly over a long period, shown by the bright red signal. The blue ‘dots’ identify cell DNA-containing nuclei, which could belong to muscle cells, immune cells, or other cell types. For instance, the wavy diagonal line of blue cells indicates the animal’s taste buds.

Right image: Without adequate immune suppression, chronic inflammation can develop. The dense blue DNA-containing nuclei in this image represent immune cells (T cells and macrophages) infiltrating the muscle. Their presence reduces light-sensitive protein expression, shown by the faint red signal, leading to weak muscle contractions under light stimulation and ineffective airway dilation.

Ella Lambert

PhD Student

Faculty of Science

ella.lambert@unsw.edu.au

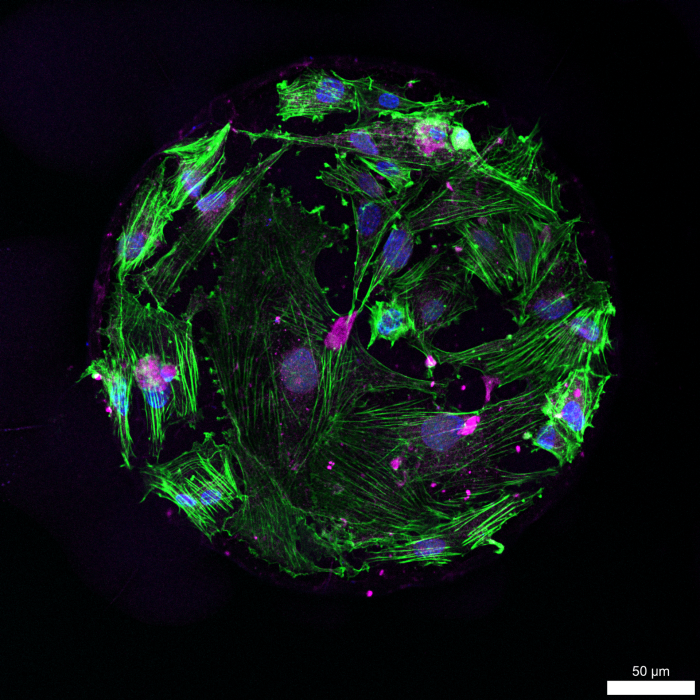

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM 800

Chicken connective tissue cells (green) are grown in a circular pattern on a hydrogel (lab jelly) to study how spatial confinement and geometry can alter their behaviour.

Yu Lei

PhD Student

UNSW School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering

z5493509@ad.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: FEI Nova NanoSEM 450

In the silent microscopic world, these open “mouths” seem to release cries frozen in time. In fact, this picture is the char (a carbon-rich residue formed during burning) of polyurethane foam coated with MXene and chitosan. The hollow structure that once gave the foam lightness now tells a new story: the char layer helps slow fire spread and highlights the role of advanced flame-retardant materials in improving safety.

Qinyu Li

Research Assistant

UNSW School of Chemistry

qinyu.li@student.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: JEOL F200 (HILMER)

Our research focuses on a new catalyst – a special type of substance that speeds up chemical reactions. Our catalysts are made from tiny platinum pieces scattered on flower/ popcorn-like iron nanoparticles, which are tiny particles that are invisible to the naked eye. Our goal was to improve the production of hydrogen fuel from water. We found that if the iron particles rust (oxidise), they make the platinum less effective. This tells us we must protect the iron from rusting to create better and more stable catalysts for clean energy, which can be used to power vehicles and homes as a replacement for fossil fuels.

In this microscopic view, the platinum glimmers like starlight, promising to boost hydrogen fuel production. However, the surrounding iron haze shows how rust can weaken their power. This highlights a key challenge in our journey to clean energy, which is both illuminated by our discovery and obscured by the need for a stable catalyst for a cleaner future.

Reprinted with permission from Li, Q et al. (2025), Crystal Growth and Design, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.5c00742. Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society.

Dr Bo Lin

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering

bo.lin@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: FEI Nova NanoSEM 450

‘Maze After the Flame’ shows what remains when fire meets a protected material. This close-up of soft foam with a fire-protective coating reveals tiny walls and passages still standing after intense heat—a miniature maze that shows how the right protection helps materials keep their shape long after the flames have passed.

-

Microscope: FEI Nova NanoSEM 450

‘Specter in the Ash’ looks like a faceless figure cloaked in shadow, arms outstretched. In reality, it is a close-up of foam protected by a flame-retardant coating. Even after fire, the structure remains, its shapes forming what seems like a ghost emerging from the smoke. It’s a reminder that protection can leave beauty—and mystery—behind, even in the harshest conditions.

Ellie Mok

PhD Student

Garvan Institute of Medical Research / UNSW School of Clinical Medicine

e.mok@garvan.org.au

-

Microscope: Olympus VS200

This image reveals the hidden scaffolding inside a pancreatic tumour under fluorescence imaging. The glowing fibres are collagen, the structure that helps hold tissues and cells together. In cancer, collagen forms a dense and tangled scaffold around tumour cells, influencing how the disease grows and spreads. Understanding this scaffold is key to developing better treatments, as it plays a major role in how tumours become resistant against therapy and interact with their surroundings.

Lamia Nureen

Research Assistant

UNSW Faculty of Medicine and Health

l.nureen@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM 880

This artwork represents the outer structural features of a healthy mouse eye which contains three different tissues: cornea, limbus and conjunctiva. This image represents multiple images stitched together to create a wholistic view of these tissue boundaries, which almost appear as a jungle (or open to your interpretation!).

The trees and branches sprouting from the side represent blood vessels (yellow) and nerves (red) in an area of the eye called the "limbus". The bright green colour embedded with nerves on each margin represents a specific protein that marks the beginning of conjunctiva tissue. The beginning of horizontally directed nerves marks the cornea boundary while the feeling of being "trapped" captured by the web-like appearance of nerves in the middle depicts an intricate corneal nerve supply that accounts for its lack of blood vessels.

By visualising the eye in this way, we can better understand how its structural organisation aids tissue function, in order to develop new therapies for corneal diseases.

Dr Lily Pearson

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Biomedical Medicine

lily.pearson@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Lightsheet Z1

Neurons don’t just exist in the brain, they also let us hear, balance, and taste. This 3D image shows two proteins, Peripherin (white) and mCherry (red), in the ear and nearby nerves.

Peripherin helps neurons branch out and fine-tune reflexes, like blocking background noise or keeping us steady when we move. The red mCherry neurons were designed to copy Peripherin, but they highlight different cells, showing how genes can behave in unexpected ways. Understanding where these neurons are located using microscopy is key to revealing how our senses stay protected and connected.

Dr Valentina Rodriguez Paris

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

v.rodriguezparis@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Leica Stellaris 8

Meiosis is the process by which one cell divides twice to produce four cells. This process only occurs in germ cells, which are the cells that go on to produce oocytes (eggs) in biological females and sperm in biological males. Here we can see several sperm-precursor cells that will eventually produce sperm at different stages of meiosis. The circular shape is due to the cells being encapsulated in the seminiferous tubule where the sperm develops, although sperm is not shown in this image. The image you see here highlights the many possibilities of giving rise to life, as each of these cells, once converted into sperm, and if combined with an egg, will give rise to a living being.

Dr Sara Romanazzo

Mid-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Chemistry

s.romanazzo@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss 800

This picture shows a ball-shaped mini-tumor model made by combining stem cells (“starter-cells”) and breast cancer cells (green) in the lab. The red colour shows the appearance of resistant breast cancer cells. Mixing the two cell types helps us understand how we could generate resistant cancer cells in the lab, and be able to study them to find potential treatments for breast cancer.

Dr Claire Sayers

Mid-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

c.sayers@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Leica M205FA Stereomicroscope

Pictured are mosquitoes infected with malaria parasites that are genetically modified to express a green fluorescent protein. After a mosquito ingests infected blood, the parasites invade the mosquito gut wall and develop into cysts in which the parasites grow. A week later, hundreds of green cysts can be seen glowing through the mosquito’s abdomen under a fluorescence microscope. Thousands of parasites within the cysts burst free and invade the mosquito salivary glands, ready to infect a new host when the mosquito takes another blood meal. By making malaria parasites glow with fluorescent proteins, we can use microscopes to watch how the parasites develop, spread and respond to treatments and interventions such as drugs and vaccines. Understanding the biology of malaria parasites allows us to uncover their weaknesses, paving the way for new strategies to treat, prevent, and ultimately eradicate this deadly disease.

Dr Giulia Silvani

Mid-Career Researcher

UNSW Faculty of Science

g.silvani@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Olympus FV4000

This image captures brain cancer cells (glioblastoma, inner circle) breaking through the wall of a tiny artificial blood vessel (outer circular structure), recreated on a microfluidic chip, a miniature “lab-on-a-chip" that mimics how blood flows in the body. By watching how these cells invade the vessel under realistic, flowing conditions, researchers can better understand how aggressive cancers spread and test new ways to stop them, without the need for animal models.

Thai Hong Anh Tran

Honours Student

UNSW School of Biomedical Sciences

z5422352@ad.unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: Zeiss LSM 900

This is a 400x original magnification image showing the staining pattern of two biological markers located in the healthy conjunctiva, which is the thin layer covering the white of the eye and the inside of the eyelids. The magenta shows a novel gene currently under research, and the cyan shows Cytokeratin 8 (K8), a thread-like protein that gives conjunctival cells their shape and strength.

K8 is one of many biomarkers clinically used to diagnose conjunctivalisation, a disease process where abnormal tissue from the conjunctiva grows over the cornea, resulting in blindness. Unfortunately, these biomarkers are not always reliable for clinical diagnosis as they can also be found on other areas of the eye or be naturally present under healthy conditions. In our study, we found that the novel biomarker (magenta) appears on diseased corneal tissue of mice but not in their healthy corneal tissue. This specificity could be key to identifying the mechanism driving conjunctivalisation and allow for better patient outcome by providing earlier diagnosis and therapeutic interventions.

Artistically, these colours evoke the image of a fire burning in the rain - a reminder that even under diseased conditions, nature continues to shine. In the same way, we too can choose to shine in the face of scientific challenges, letting persistence light our path towards discovery.

Dr Umme Laila Urmi

Early-Career Researcher

UNSW School of Optometry and Vision Science

m.urmi@unsw.edu.au

-

Microscope: FEI Tecnai G2 20 transmission electron microscope

This is what the flu virus looks like up close - tiny, spiky, and ready to cause trouble. My research focuses on fighting viruses like this using special molecules called peptides. These act like tiny bodyguards, stopping viruses before they make us sick. One day, they could help stop the spread of viruses from things we touch, like doorknobs or stairs.

This work is under the Creative Commons CC-BY license and has been adapted from Urmi, UL et al. (2025), Virology, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2025.110599.